Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 9 July 2020 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sir Robert Watson

By Madushka Balasuriya

Viruses such as COVID-19 might only be the “beginning of the line” if the issue of climate change is not prioritised by world leaders, a leading climate scientist has warned, adding that economic and financial systems will also need to evolve if the threat is to be dealt with adequately.

“Wild animals have a huge number of zoonotic pathogens. There are probably 1.6 million potential viruses in mammals and birds, and probably about half of those – 700,000 – could pose a risk to human health,” explained Sir Robert Watson in an online lecture recently, organised by the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka.

Watson, apart from being bestowed a knighthood for his ground-breaking work in helping synthesise scientific knowledge concerning a hole in the stratospheric ozone layer above Antarctica, has held posts as a Scientific Advisor at the White House and Chief Scientist at the World Bank, among other high level postings over his decades long career. It’s safe to say, there are not many more accomplished voices in the field of climate science.

It is therefore a little concerning when he says that he expects climate change to exacerbate not only heat stress, extreme weather events, and the prevalence of vector-borne diseases such as dengue, chikungunya and zika, but also zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19.

“So SARS and COVID-19 are not the end of the line, they may be the beginning of the line of increased zoonotic diseases. Over 75% of all new infections have their origins in animals.”

Zoonotic diseases, to be clear, refer to diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans; Ebola, SARS and COVID-19 all fall under this definition. For years scientists and experts have warned that it was only a matter of time before a highly lethal and infectious zoonotic virus made the leap from animal to human being. With the COVID-19 outbreak, their warnings have proved to be accurate, though even now they expect something potentially worse in the future.

While it’s true that the mutation of such viruses cannot be controlled, the reality is that human beings nevertheless have been actively increasing the odds of infection. Many will have become familiar with the term ‘wet markets,’ markets where wildlife is caged, traded and sold as meat; with many different species located in close proximity, it’s not a matter of if, but when, in terms of a virus jumping from animal to animal before mutating to a point that it can infect a human.

However, wet markets are only the tip of the proverbial iceberg, according to Watson, who says that deforestation plays an even bigger role in the spread of zoonotic viruses.

“We have more contact with animals now as a result of more and more deforestation, and we humans go in to those areas,” he stated. “And as we’ve deforested, we’ve used a lot of this land for commercial livestock farms. So we’ve now got livestock interacting with wild animals and contracting diseases, which can then be passed on to humans.”

Add to this, direct human-wild life interaction as humans encroach on newly deforested areas, and it fast becomes a recipe for disaster.

Economic growth is not the way forward

The topic of climate change in recent times has arguably reached a point of over saturation; one could argue that it’s a problem that is fast reaching the same levels of social apathy as issues such as poverty and war. This is not to say poverty and war are not serious issues, rather that as a society many of us have become desensitised to its horrors; more willing to accept that it is ‘part of the world’.

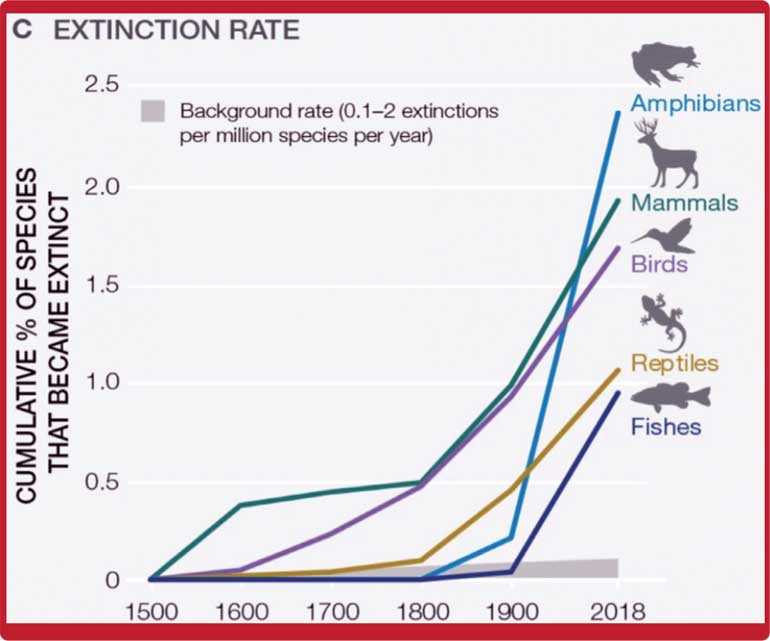

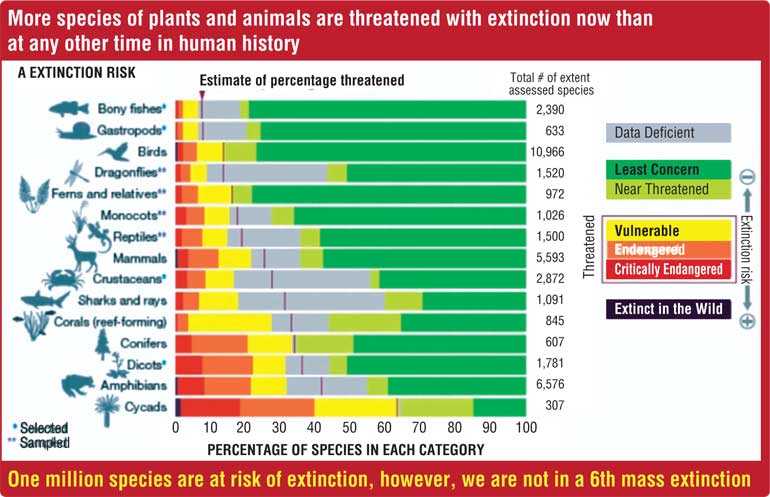

In terms of climate change, even putting forward statistics such as the following might not be enough nowadays to convince a ‘climate change denier’: Increase in floods and droughts (as has been experienced in recent years); increase in diseases and extreme weather events such as hurricanes (again experienced more frequently in recent years); 75% of the land area on Earth has been significantly altered, negatively impacting the well-being of 3.2 billion people; 66% of the ocean area is already highly modified and degraded; only 3% of the ocean is unaffected by human activity; 85% of wetland area has been lost.

Sri Lanka in particular is set to be harshly impacted with ocean acidification predicted to adversely impact fisheries and coral reefs.

But even with all these stats and figures we were still well on course for the point of saturation - and we still might get there - but COVID-19 might just have given us glimpse of an alternative solution.

“Every government in the world has to be thinking how do we recover economically from COVID? This gives them an opportunity for them to be a green recovery. Move to a low carbon economy, invest in renewable energy, invest in energy efficiency, make sure that we invest safeguarding nature,” states Watson.

“Many of the European governments said that this is what they plan to do, but I can’t see Brazil, I can’t see Russia, I can’t see the US, being willing to do that. But if we think this through, we could use this pandemic and the need to economically recover from this pandemic, with a much more sustainable set of projects, technologies and policies. Sustainable production, sustainable consumption.

“But to be honest, I’m not overly optimistic that that’s what will happen. But we do have an opportunity.”

Indeed, we do have an opportunity. In Sri Lanka itself, we have seen how companies, when push comes to shove, have managed to make ‘work from home’ a reality. This has seen far less cars on the road, drastically reducing noise and environmental pollution. And while the tragedy of job mass scale job losses cannot ever be understated, the best solution for all concerned, believes Watson, is to reframe what it means to be a successful economy.

“We need to change our governance. Everybody needs to be involved in decision making - governments, private sector, local people, NGOs, everybody.

“We need to evolve and transform our economic systems; measuring economic growth with GDP is not good enough. We need to recognise that nature has economic value, both what we call market and non-market; governments must take this into account when they make decisions.”

Watson however is acutely aware that much of this is easier said than done. Nature-based solutions such as reforestation with native vegetation can have multiple benefits, he explains, but adds that they can also have negatives. Large scale afforestation – that is growing forests on land that was never forests – and large scale bioenergy, can actually undermine biodiversity if monoculture crops are used, which can then undermine food and water security, notes Watson.

But he nevertheless strikes an optimistic tone regarding a shift in private sector priorities which he feels may rub off on governments.

“Where I’ve become a little bit more optimistic recently is that many of the major businesses in the world have started to realise that climate change and loss of biodiversity is not in the best interest of big business. And so at the World Economic Forum, they recognised that the five biggest threats to their industries are all environmental. Business now has started to realise that they must fight.”

The need for transformative change

According to Watson, the most reliable way to go about this is through cross-sectoral planning, whereby a focus on agriculture also requires a look at water, transportation, energy etc.

In addition to this Watson believes the environmental costs of goods and services need to be internalised into their prices.

“Therefore we need to move away from the economic system we have today. That’s not moving away from capitalism, it’s that we need to do capitalism in a different way.

“We need incentives for good practices and good policies. And we need to think through, especially in developed countries, what’s a social narrative for good quality of life. Is it three cars? Is it a bigger and bigger house? These are all unsustainable, and so we in the rich world, and affluent people in developing countries, really need to think through what’s important to life. How much material goods and services do we need?”

In terms of how we go about it, Watson is wary of the fact that many developing countries are hesitant to forego cheap energy and fast economic growth when developing countries have already reaped seemingly rich rewards for the same in decades past. For this, Watson has some sincere and sobering advice.

“There’s a lack of trust between governments. A lack of trust between the private sector NGOs and governments. The UN is not trusted by some governments. There are vested interests and power asymmetries, and there is corruption in government and private sector. There are many people that like the status quo – cheap energy, cheap food, perverse subsidies, reliance on GDP as a measure of economic growth, which is not a measure of sustainable growth.

“And often we take a very short term perspective. We look at what we need in two to five years rather than looking at what we need in 10-20 years. Politicians need to be re-elected so they have a short term perspective. The private sector wants to see profits for their shareholders, so too often we look short term not long term.

“But we can do it. We can have good economic development in developing countries by learning from the mistakes we’ve made in industrialised countries.

“We humans are changing the climate. We’re losing biodiversity. It’s undermining human wellbeing. And there are policies and technologies that can be used for all of us to become more sustainable, and a more equal world where we leave nobody behind.”