Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 18 October 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Reviewed by Lal Medawattegedara

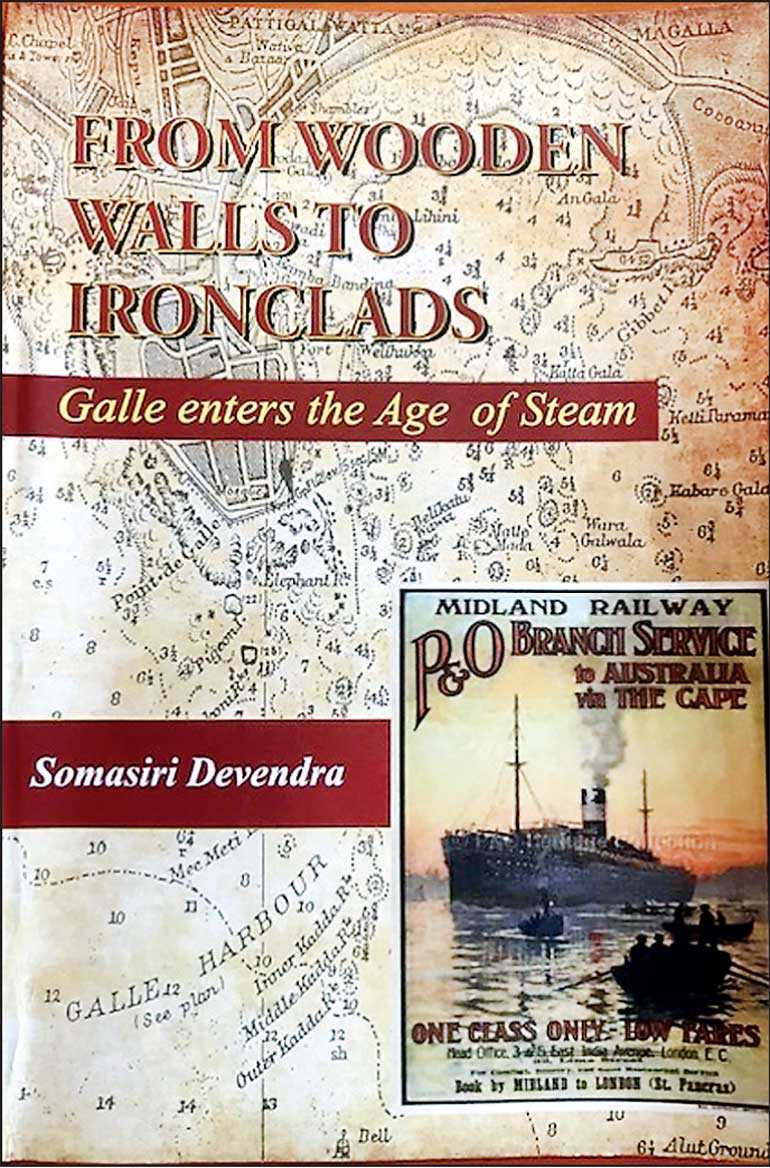

There is something dignified about a ‘booklet’ that carries a historical narrative. Possibly because of the clash of dimensions – could size compete with something as complex (and troublesome?) as history? Somasiri Devendra, one of Sri Lanka’s established enthusiast, observer, researcher and writer of maritime heritage, offers such a challenge in his new book ‘From Wooden Walls to Ironclads—Galle Enters the Age of Steam’.

It sets out to achieve an ambitious task of recovering from the deep chasms of time, the evolutionary history of the ‘medieval port’ of Galle. If this southern port was wrecked by the currents of economic trends of the times, this book implicitly attempts to present the story from the side of the victim in five chapters with thematic narratives of the mixed fortunes of the Galle Port.

The book begins by tracing the history of the Galle Port, whereby the author argues that the port could have come into significance only after the 10 ACE – though there were textual evidences of its prior existence in the ancient chronicles.

Yet, it was the Portuguese who discovered this port by a mistake (author does not elaborate on this important ‘mistake’), and they used this port as a pivotal point for their imperial ambitions, and might have been responsible for much of its significance that followed.

The second chapter attempts to focus the on the events that could have resulted in the change of fortunes of the Galle Harbour. This chapter also focuses on the shipwrecks in and around the harbour and enhances these narratives with maps and rare photographs. The author offers a comprehensive and an interesting list of wreck sites around the harbour with maps – these wreck sites being cited as one of the possible reasons for Galle to lose its lustre as a port of call.

Chapter III is the saddest one in the book, for its carries the reader through what the author calls the “flowering and fading” of the Galle Port. This chapter traces the modes by which the harbour responded to the challenges posed by the steam ships; the operational modes of the Royal Mail and their pigeons (who could fly 72 miles in 45 minutes in good weather conditions); and the crew from the Maldivian Bugalows – known as ‘yahalu minnussu’ – who worked as casual labours in Galle.

Despite the author’s attempt to stay objective, one cannot help but feel the subtle regrets and desolation felt him towards the twilight of the harbour. The fourth chapter is an attempt to recover some of the lost geographical landmarks of the Galle Harbour as well as the fort.

The author uses an interesting sources to arrive at his conclusions – the notes left by the pilots in the port. The book interestingly offers all these notes in the appendix – a worthy endeavour considering that the originals were lost to the destructive power of Tsunami. Chapter five is a short text that sums up the ending of the Galle Port.

The book offers interesting maps, photographs and artistic impressions to complement its content. The glossy-paper printing adds value to this great bookish endeavour.

As far as this writer is concerned From Wooden Walls to Ironclads is a noteworthy addition to the exiting material available on the Galle Port. The fact that the author had borne the cost of publishing makes it a beautiful labour of love. The book of course could benefit from several additions.

Structurally, the book requires a narrative voice – that voice is at times disrupted by the variety of materials presented in the book. The brevity of the ambitious account demands a moderated narrative voice. The book could do with a comprehensive reference list – rather than footnotes – and a glossary, for sensitive readers would find such components absolutely useful.

At the same time, the clarity of some of the maps and photos has suffered due to the reduced space. Possibly all this could be rectified if the scope of the book could be expanded say in a second edition. A bigger bolder and an expanded version of the book (with sponsorships) is always a possibility considering the interesting account the author had begun.

Some of the interesting subtopics in the book, like the Royal Mail pigeons, odd-job workers from the Maldivian ships, and Ship Pilot’s notes, to mention a few, are topics of interest in their own right – and they deserve further elucidation.

All in all, the author had presented to his readers a highly readable and well documented account of an event in maritime history that adds fresh perspectives to the existing scholarship on the subject.