Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 25 October 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

An opponent of trade liberalisation has recently tried to score a cheap debating point by questioning the need to create one million jobs. His argument has been that the official statistics showed only 400,000 unemployed persons.

If we are to escape from the middle-income trap and get established on a high-growth trajectory, it is imperative that all sectors of society understand the importance of creating jobs with the characteristics demanded by our young people and by the women who are sitting out the job market – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

If we are to escape from the middle-income trap and get established on a high-growth trajectory, it is imperative that all sectors of society understand the importance of creating jobs with the characteristics demanded by our young people and by the women who are sitting out the job market – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

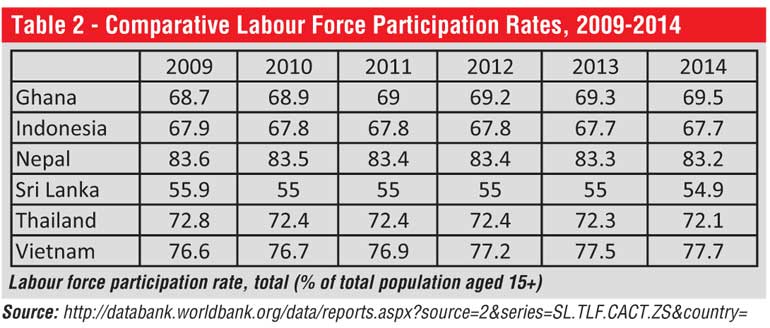

The unemployment rate is the number of people actively looking for a job as a percentage of the labour force. It is not a percentage of the population as a whole but of the labour force, or those who are working or looking for work. According to the Department of Census and Statistics, it was 4.2% at the end of the first quarter of 2016. Taking the most recent numbers from the 2014 Labour  Force Survey, this yields a number higher than, but still in the range indicated by our debater: 548,000. Table 1 gives the numbers from the Labour Force Survey for 2009-2014.

Force Survey, this yields a number higher than, but still in the range indicated by our debater: 548,000. Table 1 gives the numbers from the Labour Force Survey for 2009-2014.

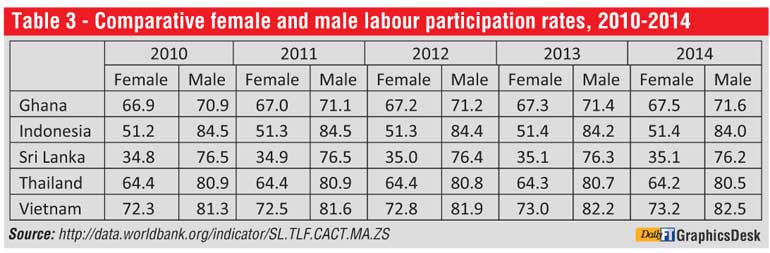

Given the denominator of the unemployment rate is the labour force, the next step is to look at the labour force participation rate. Table 2 shows Sri Lanka to be an outlier among its peers.

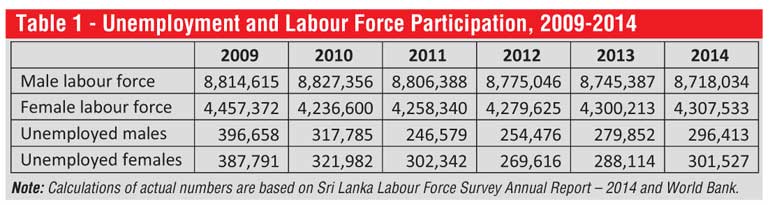

Given that the female labour force is half the size of the male labour force, this suggests a look at gender-disaggregated data in Table 3.

Sri Lanka’s male labour force participation is not an outlier. But the female rate is radically low.

According to the most recent Household Income and Expenditure Survey of 2012, the average household in Sri Lanka ranges from 4.3 people in the estate sector to 3.8 in the rural. The number of income receivers ranges from a high of 2.1 in the estate sector to 1.7 in the rural. For the country as a whole, there are 1.8 income receivers in a household of 3.9 persons, on average.

If the female labour force participation rate could be raised to the levels in comparator countries or at least to the level of the estate sector across the economy, household incomes would be considerably higher. A disproportionately large number of women are staying out of the labour force. Given they are willing to undertake work in foreign countries, this suggests that the jobs on offer in Sri Lanka are not attractive enough to bring them into the market.

In addition, the unemployment rate among the 20-29 year-olds is roughly three times the overall rate. They are looking for work, but are unwilling to take what is on offer. As the long lines for the Korean language exams showed vividly, they are not unwilling to work, or even wait in line overnight to qualify for work at acceptable rates of compensation.

So, here is the nub of the problem. The jobs currently available in Sri Lanka are unattractive.

If we are to escape from the middle-income trap and get established on a high-growth trajectory, it is imperative that all sectors of society understand the importance of creating jobs with the characteristics demanded by our young people and by the women who are sitting out the job market. These characteristics include, but are not limited to, adequate salaries perhaps in excess of Rs. 40-45,000 a month as stated by the Prime Minister recently. Jobs that involve hard labour in the outdoors such as work in the booming construction industry and in commercial agriculture will require even more.

If these conditions are met, those labouring in the Middle East and elsewhere can attracted back home and those under-employed and sitting in three-wheelers under trees redirected to remunerative jobs. There will, of course, be shortages of labour for low-end jobs that do not meet these conditions. Plantation companies, for example, are likely to have to close down unless they can offer decent work at decent wages.

It is in this light that we must look at the target of one million jobs in five years (or, an average of 200,000 new, attractive jobs every year). This is an objective worthy of the support of all sectors and interests in our society. It is a sad testimony to the quality of economic discourse in this country that this kind of economy-transforming objective and policy has been reduced to a cheap debating point by myopic individuals.