Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 17 March 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There are jobs but no takers.

There are jobs but no takers.

The Government says it plans to create a million jobs. This objective can be achieved only with mega investments in industry.

But are there a million unemployed, who will bless the gods for the opportunity and rush for these jobs. Perhaps not? It runs contrary to the picture we now see of jobs and no takers. The weekend papers in all languages are full of vacancies. This suggests that there are jobs but hard to find people who want them.

A chance encounter triggered a stream of thoughts about this conundrum of jobs and no takers.

There is no research data that provides a clear picture. Bits and pieces of anecdotal evidence like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle have to be put together. Hopefully that will build up into a picture that will shed some light and unravel the conundrum.

Now back to the chance encounter. The Colombo Gin Club had arranged a tasting of eight different gins. It was held at a restaurant  at Park Street Mews. The first flight of four gins and fever tree tonic was on the table and the gin ‘sommelier’ gave a little story about each gin.

at Park Street Mews. The first flight of four gins and fever tree tonic was on the table and the gin ‘sommelier’ gave a little story about each gin.

After four gins everyone became chattier. I asked the lovely ‘foreign’ lady seated next to me how long she had been in Sri Lanka. She surprised me by saying 20 years and added that they have a successful export business in the Katunayake industrial estate. They export leather garments.

To keep the chat up I asked whether the business is doing well, and she said, the demand was excellent but their problem was meeting the demand. “We can’t find machine operators and other staff to increase production.”

I thought to myself, she is good looking but she might be a holy terror as an employer, and that’s why she cannot get staff. Clever lady read my mind and said with smile: “It is not only us but everyone at Katunayake has the same problem, they cannot find staff.”

On reflection I was not surprised, as even with my gin-fuzzled mind I did recall that many garment factories at Katunayake had closed down as they could not get staff.

So what pieces did this give for the jigsaw? Two pieces I think. In that part of the Western Province there are no unemployed prepared to work in factories. From faraway places people are reluctant to come as renting a place to stay and buying food from boutiques is expensive and that takes up most of the salary.

I was seated next to my brother-in-law Derek Wijeyaratne, the Rockland boss, who invited me to this gin session. My mind went back to the domestic staff scene when Derek used to cycle slowly past our house in Gregory’s Road trying to tease a smile from my nangi, Assuntha.

The people in big houses then generally had an “appu” to do Western food, an “amme” for curry and hoppers, etc., an “ayah” and a “boy kolla” who did the sweeping and cleaning, and a gardener, and a driver. They all lived in, and with all meals provided as the staff were from faraway villages. They saved the whole salary and took it back home once a month.

The middle class all over the country had at least one domestic staff. The demand for domestic staff is still there. But no interest. People are vainly looking for staff that are hard to find except at rates that exceed starting clerical salaries.

What pieces do we get for the jigsaw? There is a demand for domestic staff but no takers. People in the rural areas are much better off, and no longer want to be domestics. If family circumstances are difficult, the women will go abroad and do domestic work for a salary way above the rates in Sri Lanka.

I have an agricultural property in a very rural area. I have been wandering around the area, using it as a sample survey to squeeze out of it as many learnings as possible about the rural scene. The sample is too small to claim an accurate national profile but yields a lot that is interesting.

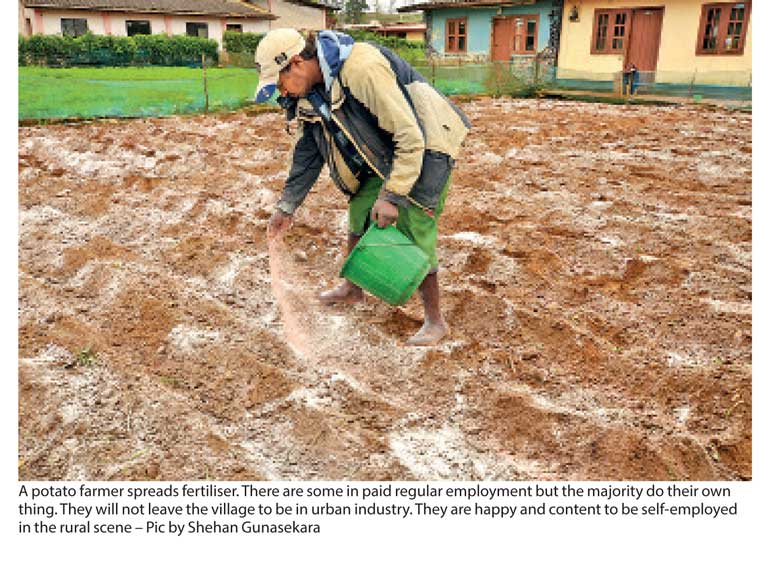

There are some in paid regular employment but the majority do their own thing. People working on similar properties as permanent staff get a salary plus EPF and ETF contributions, a house, free electricity, etc. From time to time we need extra temporary daily paid staff. It is almost impossible to find them. In the slack season between sowing and harvesting it might be possible to entice a few to come and work but by and large they are hard to find.

Most of the women do not do anything on a fulltime basis. They will happily come for short-term work of a few days at a time like manuring (cutting trenches, putting fertiliser, and closing them), collecting coconuts after the pick or collecting cashew during its annual season.

The men in regular employment have no reason to move to work in industry elsewhere. These women are not likely to come to fill the demand in urban areas for domestic staff.

Some are specialists like the coconut pluckers who use long sticks with a knife at the end to cut the bunches of coconuts. This is a skilled operation. To select the mature bunch leaving the immature ones for the next pick and ensuring that the nuts do not fall on the head of the picker. They all come by motorbike. I believe some of the cinnamon peelers come by car.

The electricians, plumbers and carpenters roam around a wide area. Some on bicycles and others on motor bicycles or in tuk-tuks. If you clap your hands no one will come running. After many calls it will be “l will try and come sometime next week”.

They will not leave the village to be in urban industry. They are happy and content to be self-employed in the rural scene.

Agriculture and industry

Paddy cultivation is the main activity. They are generally ancestral occupations, the sons succeeding the fathers. In their home gardens you see manioc, bananas, vegetables, cashew trees, mangoes, pineapple, etc. The family income is not solely from paddy cultivation.

There are tile factories and a variety of brickmaking plants. Some are large factories, but there are also many cottage industry brick kilns. A lot of pottery. As clay is required for the tiles and bricks, making pots is a natural extension.

Agriculture and tiles and bricks are traditional occupations. They have continued over the years and there is no apprehension that the demand will disappear.

Those in agriculture and tile, brick and pottery are not likely to migrate to urban areas or to industrial estates far away.

There are small to medium towns nearby. Some people go to work in shops, restaurants, service-related activities or clerical work in small businesses. It is always an easy commute to work and back home for dinner.

Houses are in small clusters, creating mini villages within a larger village. Children build on the parents’ land and live next to their parents.

It is easy to get to work. A little walk (walking four or five miles is a stroll) or it is a short bicycle ride. Children go to local schools. The small ones are taken by the mothers on their bicycles or motor bicycles. Everybody is home for dinner.

After a hard day’s work one could sit on a bund with a buddy, overlooking acres of paddy land. A sip of arro whilst the sun goes down and paints the sky in a variety of soft colours. Then as dusk sets in a walk back to a home where there is food for everyone.

When you put the pieces together it does not build up to a complex picture. There is a simplicity and sameness in the picture. Those living in the rural areas are content, and not likely to migrate to cities with their families to live in rented accommodation in urban slums.

There is something special about living in small villages. Security, companionship, and an easy way of life with the freedom to do what you want most of the time. They are no longer isolated, cut away from what happens elsewhere. The TV brings it all to them.

The million jobs will not get filled with urban industry or industrial parks. The only way to move some who are perhaps underemployed in the rural scene, like the younger son who is really surplus to the needs of the family agriculture venture, is to bring industry to the rural industries. Many, many years ago I believe President Premadasa saw clearly the need to bring industry to the rural areas. But we are good at forgetting good things.