Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 6 August 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The post-8 January public seek more than just cosmetic changes in the body politic. They seek systemic, institutional change. They seek to reclaim the republic. Is any political party really ready to deliver?

In the wee hours of 17 May 2012, police encountered a burning vehicle on Park Road, Colombo 05. The car crashed into a ditch  outside Shalika Grounds and exploded on impact even though nobody reports hearing an explosion in the highly residential neighbourhood that night. The charred remains found inside the burning car were identified in due course as a popular young Sri Lankan rugby player who had formerly captained the Havelock Sports Club rugby side. The police said the victim, Wasim Thajudeen, had been tragically killed in a road accident on the way to the airport. The young man had lost control of the vehicle, police reported at the time.

outside Shalika Grounds and exploded on impact even though nobody reports hearing an explosion in the highly residential neighbourhood that night. The charred remains found inside the burning car were identified in due course as a popular young Sri Lankan rugby player who had formerly captained the Havelock Sports Club rugby side. The police said the victim, Wasim Thajudeen, had been tragically killed in a road accident on the way to the airport. The young man had lost control of the vehicle, police reported at the time.

Three years later, a Colombo court is to consider exhuming the sportsman’s body for further investigation after the Criminal Investigation Department revealed his death had not been accidental. Inexplicably delayed reports from the Judicial Medical Officer and the Government Analyst had now revealed that Thajudeen was severely tortured before his death, his teeth broken and limbs slashed with broken glass. His injuries also revealed the rugby player had suffered trauma from a blunt object.

As late as 28 July 2015, the Judicial Medical Officer had failed to submit the final autopsy report into Thajudeen’s death, prompting the Colombo Magistrate’s Court to call for the full report following a request by the CID. CID sleuths now seek exhumation of the body to conduct a full forensic investigation of the rugby player’s remains. Court is likely to grant its permission and the exhumation could take place as soon as 10 August, police sources claim. At the Muslim burial grounds in Dehiwala, Thajudeen’s gravesite is being afforded 24-hour protection.

Nobody knows why Wasim Thajudeen had to die. There is rampant speculation and there are tall stories. But in the public psyche, the high-profile case was deemed intrinsically political in nature just days after the ‘accident’ took place.

The former ruling family’s affiliation with the sport of rugby in Sri Lanka may have fuelled the speculation. There was talk of a love triangle involving the offspring of a VVIP. Thajudeen was also believed to have been a young man with a swagger and a tendency to shoot off his mouth, reckless about who he might have been crossing with arrogant words.

The fact that the police appeared to be ignoring vital clues pointing to a more mysterious death gave the rumour mill fodder. Law enforcement authorities failed to explain the fact that Thajudeen’s wallet had turned up in Kirulapone, seemingly untouched by the fire a few days after his death. It was difficult to understand why the boundary wall of Shalika Grounds and the drain into which the car had smashed had remained unscathed in the crash and explosion.

And then there were the delayed medical reports.

The Government Analyst report on the crash site was eventually released only in January this year, and the report declined to provide an opinion on the death due to a lack of physical evidence. It was the JMO findings, pointing to severe torture before death, that convinced the CID Thajudeen had in fact, been murdered.

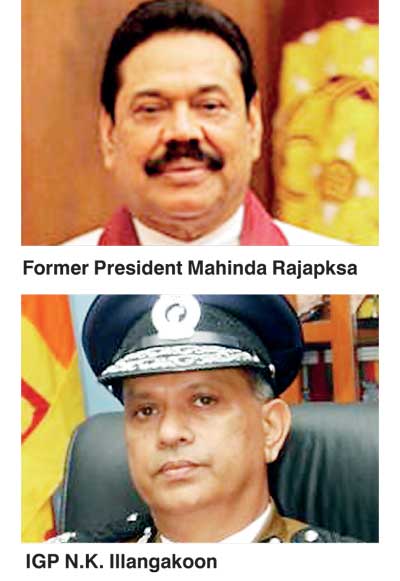

The deaths of Thajudeen and slain journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge have something in common. There also appeared to be some similarity between the rugby player’s death and the case of missing cartoonist and scribe Prageeth Ekneligoda, who disappeared in January 2010. Something about these three cases prompted IGP N.K. Illangakoon to reopen the files and launch fresh investigations in February 2015, just weeks after President Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated in presidential elections held in January.

The same day, the IGP also announced fresh inquiries into the controversial Welikada prison riot and the Weliweriya killings during a public demonstration for clean water. A single thread was running through every case handpicked for re-visitation by the police after the presidential election. There was a political dimension to every case; with every one of the killings, the culture of impunity and lawlessness actively fostered by the former political leadership had allowed the killers to go unpunished for their crimes. Thajudeen had been thrown into the pile of controversial cases by the IGP, confirming public suspicion simmering for years and spoken of only in hushed tones at dinner parties around Colombo where the sportsman was best known, that there was more to his death than meets the eye.

Taking responsibility

The CID has taken the IGP’s orders seriously, and proved their sleuthing skills, especially with Thajudeen’s murder. Similar revelations are expected over the next week about the Ekneligoda disappearance, with some reports also emerging that at least two high-profile military men could be arrested in connection with the missing scribe’s case.

Impunity afforded through political patronage or as a result of a culture of lawlessness and political violence, has been an age-old problem in Sri Lanka. The Rajapaksa regime protected murderers and rapists, provided they were unfailingly loyal to the ruling family – this is well-known. It is also universally acknowledged that the former regime had intimidated or coerced public officials into submission. This servility to political interests crippled the justice system, both at the law enforcement and judicial levels. It has deprived victims of justice and eroded public faith in key institutions of the State.

IGP Illangakoon is justifiably commended for his decision to reopen the Thajudeen and other controversial murder cases suppressed during President Rajapaksa’s tenure. But his department is yet to take the onus for failing victims and victim families because police sleuths were too afraid to cross ruling party politicos.

IGP Illangakoon owes it to the public, whose faith in his department he is attempting to rebuild, to make confessions about who stalled his investigations and demanded that evidence in these cases were suppressed. Former Police Spokesman SSP Ajith Rohana, who was retained for months following the 8 January election, blithely explained at post-election media conferences that he had been forced to twist the truth at police briefings due to political orders.

IGP Illangakoon is yet to call his former Spokesman to account over these remarks, or make him reveal which political entity forced him to knowingly relate untruthful information to the public. Corrective action to rebuild the image of the police force also begins there, with an acknowledgement of internal failings that led to gross injustice meted out to victims of political and violent crimes.

Voter psyche

It is easy to interpret the 8 January mandate as just a rejection of the Rajapaksa regime, its corruption, nepotism and authoritarian tendencies. The psyche of the Sri Lankan voter changed remarkably in that election eight months ago. For the first time in several decades, the movement for change was not just about changing faces in the political leadership. That election marked the first citizens’ affirmation in decades about the need for systemic change, institution building and republican constitution making.

Public euphoria about the passage of the 19th Amendment, even in its less potent form and outrage at the conflict of interest inherent in the Central Bank bond scandal, stem from this new civic consciousness that change must mean more than just names and faces.

Comprehension that the rot has set deep into the political system and spread through key institutions of the state, resulted in the deep disillusionment felt about the conduct of the UNP minority Government over the past eight months, and civil society activism, scrutiny and agitation for change in the election aftermath.

Public enthusiasm and stakeholdership in post-8 January politics began to dip after the Sirisena Government faced its own crises of incumbency. Corruption probes were impeded or failed to nab wrongdoers. Parliament was in a state of permanent atrophy. By all accounts, the economy was in crisis. And the Government was refusing to sack the Central Bank Governor, about whose role in the controversial bond issue was cemented in public perceptions, seriously eroding public faith in the UNP’s capacity to bring about real change. It was only Mahinda Rajapaksa’s re-entry as a candidate in the parliamentary election scheduled for 17 August that served to jolt the public out of its increasingly disillusioned reverie. The prospect of a Rajapaksa reemergence has galvanised the popular forces that came together to defeat him in January and served as a gripping reminder of the job left still unfinished by the 100-day administration of President Maithripala Sirisena after it defeated the Rajapaksa regime and all it stood for in January this year.

In essence, the Rajapaksa reentry is likely to prove an odd blessing for the United National Party-led coalition that is hoping to defeat the ex-President again on 17 August. It has reminded Sri Lankan voters of everything the country stands to lose, by way of democratic freedoms and accountability for corruption violence if the 8 January ‘revolution’ is undone by August. While neither party is expected to poll an outright majority in this month’s election to make the magic number 113, barring any major surprises over the next two weeks, electoral trends currently favour the UNFGG coalition.

The fact that the UNP-led alliance is unlikely to sweep the polls after six months in power and a restoration of fundamental freedoms and the lifting of state repression, speaks to the party’s inability to capture public imagination and convince the electorate that it has something to offer that is distinctly different to the Rajapaksa-led UPFA, except basic freedoms and a degree of de-politicisation in certain key state institutions.

Old habits

Over the past eight months, the UNP has shown an inclination to slip back into the old ways, actively cultivating an old boys club and displaying a marked reluctance to take action against old friends and former Rajapaksa acolytes who have been able to lay claim to old high school or family connections. The party has also displayed a tendency to recall old, tainted bureaucrats and cronies, most notably a former Treasury Secretary who was found to have misused and abused power by a Special Presidential Commission of Inquiry after the fall of the UNP regime in 1994. The former bureaucrat is attached to the Ministry of Economic Development headed by the Prime Minister and involved in the highways and urban development areas. The return of these old UNP hands has caused concern among the party’s freshmen politicians, whose ideological positions remain largely untainted by their brief seven months in Government.

The recall of certain party lawyers and former ministers as advisors to Prime Ministerial subcommittees on corruption, many of whom have been closely associated with the Rajapaksa regime over the past decade, have also called into question the Government’s anti-corruption drive, especially when these advisors and other top ministers in the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration were openly accused of impeding investigations into the Avant Garde floating armoury controversy by the JVP, which has sought to play the role of watchdog in the national executive council and other anti-corruption committees.

The UNP Government also showed a marked reluctance to reverse some of the previous regime’s most controversial decisions. Brigadier Deshapriya Gunewardane, the commanding officer in charge of quashing the Weliweriya water demonstration, under whose watch three young men were shot and killed by military personnel, continues to hold a diplomatic rank in Sri Lanka’s Embassy in Turkey.

Sticking to old practices

President Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe also decided to retain the services of London-based Queen’s Counsel Sir Desmond De Silva as Chairman of the international panel of experts tasked with advising the Paranagama Commission on disappearances at an astronomical cost.

The UK Bar Standards Board recently commenced an investigation into Sir Desmond’s professional conduct with regard to his role in Sri Lanka, after the Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice complained that the top lawyer had provided a legal opinion to the Sri Lankan Government in February 2014 about whether the civilian deaths incurred during the final stages of the war could be permissible collateral damage.

Thereafter, Sri Lanka Campaign said in its complaint, Sir Desmond accepted an appointment as Chairman of the Advisory Group, tasked with advising an independent commission on the same subject matter. The five-week investigation commenced on 20 July.

The Government has also decided to award a diplomatic posting to former Chief of Defence Staff Gen. Jagath Jayasuriya, whose role in the military build-up ahead of the 8 January presidential poll was questioned by the Elections Commissioner and strongly criticised by the UNP, then the Opposition at the time. As the officer to replace former Army Chief Sarath Fonseka as Commander of the Sri Lanka Army, Jayasuriya was a staunch loyalist and confidant of the former regime. The former Chief of Defence Staff is also an old boy of Royal College. Gen. Jayasuriya will leave for Brazil in a few weeks as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador to that country. Lt. Gen. Daya Ratnayake, who famously made political speeches at army cantonments ahead of elections, was similarly never called to answer for these transgressions, and instead rewarded with a diplomatic posting to Islamabad, when he completed his tenure as Army Chief earlier this year.

It was the Rajapaksa regime that turned Sri Lanka’s missions overseas into safe havens for officials and loyalists whose conduct was found wanting. Former police chief Mahinda Balasuriya was rewarded with a posting to Brazil after he controversially retired after the shooting of Katunayake Free Trade Zone worker Roshan Chanaka during a protest against a Government-proposed pension scheme for the private sector in 2011. It is a practice the UNP Government appears keen to continue.

Baby steps

Despite these major lapses, Sri Lanka is witnessing one of the most lawful election campaigns in recent memory. To attempt to influence the police or judiciary now would be to commit political suicide given the public mood.

For the first time in decades, police and election authorities have been able to enforce laws banning candidate posters and hoardings in public spaces. State media conduct during this polls campaign has not been ideal, but it is playing fairer than it has in decades. Police have made several arrests of local politicians and former MPs for breaking election laws.

A Yatinuwara Pradeshiya Sabha Member was arrested for displaying distorted versions of the national flag at a Mahinda Rajapaksa rally. Former Eastern Province Chief Minister Najeed A. Majeed was arrested yesterday for trying to intimidate voters during postal voting in Trincomalee. The police department caused shockwaves this week when they filed legal action against Deputy Minister of Justice Sujeewa Senasinghe for obstructing a police officer and failing to obtain a licence to broadcast election messaging via loudspeaker. Senasinghe is outraged and has called for the IGP’s resignation over his court summons, but the top cop is standing his ground against the Deputy Minister of Justice.

Yesterday police raided a printing press that was printing booklets slinging mud against Kurunegala District UPFA candidate and ex-President Mahinda Rajapaksa, shutting down the operation.

All these are small steps, but they are changes that were unthinkable only eight months ago. These are the true dividends of the 8 January revolution. In a political dynamic that has altered drastically since 8 January, the people are striving hard to make the rules. For the first time in a long time, public disgust about Rajapaksa excesses and impunity struck fear into the hearts of politicians who came after, if only for a brief time. If the message was not clear enough the first time, voters will have a chance to reinforce it again in two weeks.

The grave injustice meted out to a young sportsman and his grieving family because of an institutional failure wrought by rampant political interference demonstrates that it is course correction at the systemic level that is most desperately required. The odds maybe stacked slightly in the UNP’s favour if only for a lack of options, but it remains to be seen if the party is ready or able to be the custodians of a mandate born of a desire of the people to instil more than just cosmetic changes in Sri Lanka’s body politic.