Wednesday Mar 04, 2026

Wednesday Mar 04, 2026

Monday, 27 February 2017 01:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Being proactive is becoming a rarity. Protests for rights have become a regular occurrence. Conducting post-mortems after a tragedy is not something uncommon to us. All of the above point to the need for a fresh approach towards survival and success, both as individuals and institutions. Let me connect this to the interesting concept of the ‘Sigmoid Curve’. What it is all about leads us to an informative and insightful discourse of being proactive rather than reactive.

Overview

The Sigmoid Curve is named after Sigmoid, the Greek word for the letter s. It represents the curve of a new lifecycle emerging from an existing one, much like an ‘S’ on its side. It was extensively referred to by Charles Handy, an Irish-born management guru.

In the book, ‘Age of Paradox’, Handy argues that to survive and grow, all individuals and institutions must plot the point on their present lifecycle and then plan and implement transformational change. He surveys the state of the world and his observations are indeed interesting.

People have been adversely affected by change: capitalism “has not proved as flexible as it was supposed to be” and increased technology and productivity have resulted in fewer jobs for some and increased consumption for others. His solution lies in “the management of paradox”, in essence planning for the unplanned. Handy identifies nine global paradoxes. Among them, the US and Britain have the highest percentages of employed people but their workers are the least protected, in Bangladesh 90% of houses are owner-occupied, in richer Switzerland 33%, and notes that to cope with the turbulence of life, organisations must start in the mind.

Relevance of S Curve

In Western culture, life is seen as a long line starting on the left and going to the right, observes Rebeca O. Bagley writing to Forbes magazine. In fact, this is a linear path leading from “Alpha to Omega” (first and last letters of Greek alphabet). Westerners typically see things in terms of separate chunks of beginnings and ends: ages, jobs, relationships, projects, tasks, even life itself.

As we are much aware, in eastern cultures, life is viewed as a series of cycles or waves. Everything is linked and connected. Everything has its own natural life span, so that in birth there is death and in death there is new birth. This has much relevance to what Handy says about the S Curve.

If you act too early in the cycle, you lose the fruits of the present lifecycle. If you act too late, you may be on the downward curve and not able to turn things around. The key to future success is to have the foresight and discipline to see the opportunities in what you are doing in the present cycle and then to make your moves while things are going well. It is against the natural order to embrace change when all is going well but, when you plan it right, it is the best possible time because you have time, resources and morale on your side.

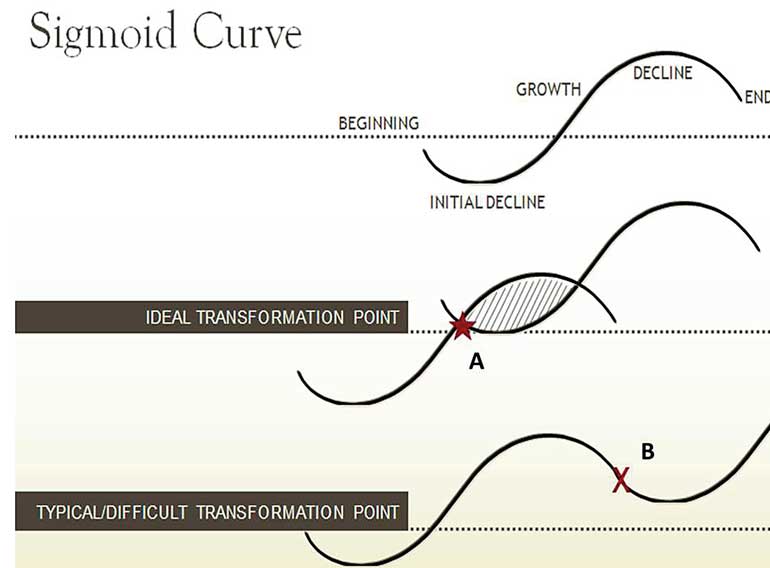

As Picture 1 illustrates, one has to be proactive in taking appropriate actions at the ideal transformation point or else it will be difficult and the actions are more of a reactive nature. The secret of constant growth is to start a new Sigmoid Curve before the first one peters out. The right place to start that second curve is at point A, where there is the time, as well as the resources and the energy to get the new curve through its initial explorations and floundering before the first curve begins to dip downwards.

We have many Sri Lankan examples to show that the real energy for change only comes when you are looking disaster in the face, at point B on the first curve. At this point, however, it is going to require a mighty effort to drag oneself up to where, by now, one should be on the second curve. To make it worse, some current business leaders are now discredited because they are seen to have led the organisation down the hill, resources are depleted and energies are low.

For an individual, an event like redundancy typically takes place at point B. It is hard, at that point, to mobilise the resources or to restore the credibility which one had at the peak. We should not be surprised, therefore, that people get depressed at this point or that institutions invariably start the change process, if they leave it until point B, by bringing in new people at the top because only people who are new to the situation will have the credibility and the different vision to lift the place back on to the second curve.

Wise are they who start the second curve at point A, because that is the “Pathway through

paradox”. That is what Handy advocates. The way to build a new future while maintaining the present. Despite that, challenges still lie ahead. The second curve, be it a new product, a new way of operating, a new strategy or a new culture, is going to be noticeably different from the old. It has to be. People also have to be different.

Those who lead the second curve are not going to be the people who led the first curve. For one thing, the continuing responsibility of those original leaders is to keep that first curve going long enough to support the early stages of the second curve. For another, they will find it emotionally difficult to abandon their first curve while it is doing so well, even if they recognise intellectually that a new curve is needed. For a time, therefore, new ideas and new people have to coexist with the old until the second curve is established and the first begins to wane.

Salient challenges of S Curve

Imagine the Sigmoid Curve as the curve of life of an individual, an organisation or an entire economic region. The curve initially declines in a time of experimenting and learning then rises in a period of growth and prosperity, and finally declines leading to the end. The key to sustaining a healthy life, a  healthy business or a healthy region is to make a transformation to a new curve before the current one is too far in decline.

healthy business or a healthy region is to make a transformation to a new curve before the current one is too far in decline.

Every living thing has a natural lifespan. So do products, projects, organisations, teams, relationships. Lifecycles are everywhere. In a day, it is wakening, preparing, activity and sleep. In a year, in some countries, there is spring, summer, autumn and winter. In a life, it is birth, growing up, maturity and death. In evolution, it is the ape-man, prehistoric man and modern man.

There are challenges that all organic entities face whether they are individuals, groups or organisations. Many organisations do not survive long. Tom Peters and Robert Waterman found this out when they revisited the top organisations featured in their 1982 book ‘In Search of Excellence’. Most had not maintained their position; some had gone under. Of the 208 companies studied over 18 years by Peters and Waterman, only three lasted the course of the whole 18 years. 53% could not maintain their performance levels for more than two years.

“The Sigmoid Curve sums up the story of life itself,” says Handy. “We start slowly, experimentally and falteringly; we wax and then we wane. It is the story of the British Empire and the Soviet Union and of all empires, always.” In another way, the Sigmoid Curve is a representation of how all animal species ensure their own survival by reproducing themselves when their adults are young, virile, fertile and healthy. Managing change and survival is at heart the way of all nature.

Lessons for Lankans

S curve and be a stimulator for Sri Lankan managers to act proactively. It requires being aware of the nature of products and services in the context of an organisation. It reminds me of the bestseller ‘Who Moved My Cheese’ by Spenser Johnson. He, through a simple parable, highlighted the need to change by saying, “Smell the cheese often so that you know when it is becoming stale.”

From an individual point of view, it invites us to look at our capabilities to update them in “sharpening the saw”. From an institutional point of view, it invites us to renew, refresh and re-launch. Both involve transformational change. Sri Lankan managers can do much better than the current level in this context. They can show their mettle in becoming more of “thinking performers” using their hands, head and heart.

(Prof. Ajantha S. Dharmasiri can be reached through [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info)