Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 28 July 2017 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The other day I met a woman who is a card-carrying member of a major political party. She is the president of the midwives association in her area. She exuded leadership. She has so much to share with her community about health, lifestyles and other matters, and that has given her a self-confidence which is evident. With all this, she was telling me about the difficulties she is having with the incumbent party leadership in her area. Worried about her rise, her own party boss is putting every obstacle in her way. This kind of Neanderthal behaviour is apparently commonly experienced by women in the lower echelons of parties. Without quotas, these women will be constantly yielding to political incumbents and their mediocre progeny.

The other day I met a woman who is a card-carrying member of a major political party. She is the president of the midwives association in her area. She exuded leadership. She has so much to share with her community about health, lifestyles and other matters, and that has given her a self-confidence which is evident. With all this, she was telling me about the difficulties she is having with the incumbent party leadership in her area. Worried about her rise, her own party boss is putting every obstacle in her way. This kind of Neanderthal behaviour is apparently commonly experienced by women in the lower echelons of parties. Without quotas, these women will be constantly yielding to political incumbents and their mediocre progeny.

I push for quotas with some unease, but her case tipped me towards a passion for the women’s quota in local government. We have fewer women in local government (apparently less than 2%) than in Parliament, which has 13 out of 225 or 6%. Female relatives of politicians do not waste their time with local government. They start high at the provincial council or national level. Women of this calibre who aspire for local leadership should be given every legislative boost possible.

Quotas are the best tools for achieving equity in representation when social norms are stacked against women in active politics. Many Asian countries including Indonesia and Bangladesh have created seats which are reserved for women nominated through party lists. It is like a national list dedicated to women.

Another method is to zip the national list or party lists. Zipping a list is to alternate the names of females and males on a party list, often starting with a woman’s name at the top. This way, returning close to 50% or more women through lists can be assured without creating a separate list for women. In both of these quotas, the idea is that women would be acclimatised to the political arena as list MPs and would begin to contest on their own.

In Sri Lanka, given the education levels of our women, we should go a little beyond, at least in local government, and ensure that women get a chance at the ground level first-past-the-post (FPP) contests too. One way to do this is to set aside certain seats as women-only seats. Another method is to mandate that a certain percent of FPP candidacies have to be given to women.

Two key amendments that define the existing local elections laws are the Act No. 22 of 2012 and the Act No. 1 of 2016. The former was legislated to change the PR system to a mixed member parallel system. Act No. 1 of 2016 was an add-on to increase women’s representation. The latter legislation uses a list dedicated to women-only as in Bangladesh or Pakistan. However, the electoral method used in the Acts and the way it is formulated through them makes implementation difficult and the Elections Commission has asked a for large number of changes to the legislation.

In the meantime, small parties are taking the opportunity to ask for a different mixed member system which they feel is less disadvantageous to them. A major challenge for the legislators is to accommodate the 25% guarantee which is in the present legislation. Small parties are requesting a switch to what is called the Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system. I too feel it is a cleaner method than the one now in the books.

According to the mixed member methods, the nomination papers submitted by a party for a 20-member council has to have two sets of names – the names of those contesting in each of the wards, followed by the names of additional members to be returned from lists. FPP results can be highly disproportionate to the actual distributions of votes to parties. The additional members are returned to bring the system closer to proportionality.

For MMP systems to work, a 60:40 ratio of “FPP seats to list seats” is prescribed. We worked out the scenario for a 20-member council where three parties, A, B and C, are contesting for 12 FPP seats and eight compensatory PR seats to see how women’s quota will work out.

Currently it is very hard for women to get on any candidate list. What is proposed by parties right now is a small quota of 10% or a  minimum of one FPP candidate per local authority.

minimum of one FPP candidate per local authority.

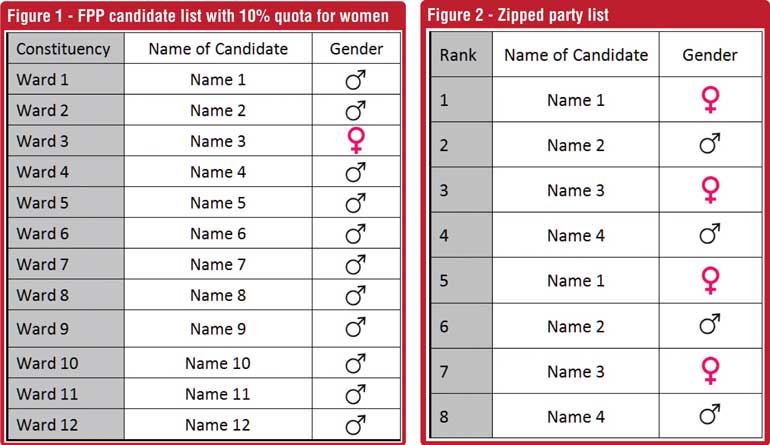

If a party does not go beyond the statutory requirement of 10%, the first half of the nomination paper would look like Figure 1.

Although it is not on the agenda, a zipped list would help legislators get close to 25% overall representation for women. If zipped lists are mandated and such lists start with a woman’s name, 50% or more of the women returned from lists will be women.

Our simulations show that women can be assured of 20% representation, but in some cases the representation can be as high as 40% depending on the way the votes are distributed across the parties. In a few cases, the representation can go down to 18% due to vagaries of arithmetic and voting patterns.

The quota for women in this manner, however, makes it almost impossible for a man to be elected from a small party. For example, in local elections held over five years ago, the JVP received one to two seats in several local authorities through the PR system operative then. If the mixed system is to be used, JVP is unlikely to receive any FPP seats, but will get 1-2 list seats in selected local authorities, if past voting patterns are a guide. In cases where JVP gets one list seat only, the men the in the party would almost have no way of being elected from those local authorities.

A correction would be to allow the secretary of any party that “does not win FPP seats and wins only one list seat” to override the list and make a selection from the full list of candidates.

The demarcation process has yielded 5000+ wards in the local government system. New proposals at the insistence of small parties is set to increase the FPP to PR ratio to 60:40, making the final number of councillors rise to almost 8000+ from the present 4853.

If the council sizes are to be doubled we might as well fill the new 3500+places with women! Therefore, I would suggest that we increase the FPP quota from the present 10% to an appropriate percent to ensure that almost all of the newly created seats are filled by women.