Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday, 21 September 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Monetary policy

Monetary policy

The primary objective of a Central Bank is to maintain the price stability of a country; in simple terms, to manage inflation at a comfortable level. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) uses policy rates and short-term benchmark interest rates to set the direction of the interest rates in order to control inflation by controlling money supply.

Since January 2016, the CBSL has increased its policy rates twice by 50 basis points (0.5%) on each occasion and has raised the Statutory Reserve Requirements (SRR) of commercial banks by 150 basis points (1.5%).

In response to the above policy rate changes, the benchmark one-year Treasury Bill rates has moved up around 350 basis points while the 10-year Treasury Bond rates has increased by nearly 250 basis points. Domestic consumer price inflation as measured by the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) jumped to 6.0% in June 2016 from 0.9% at the end of 2015 before slowing down to 4.0% in August 2016. Although the CBSL has been in tightening mode throughout this year, consumer price inflation never stayed outside the confortable zone of the CBSL reference guide.

The CBSL cited three primary concerns for the monetary policy decision taken in late July 2016 - persistent growth in bank credit to the private sector, the fiscal slippage expected with the shortfall in revenue due to a delay in or the non-implementation of VAT and other tax reforms and domestic consumer price inflation observed in prior months.

Credit growth

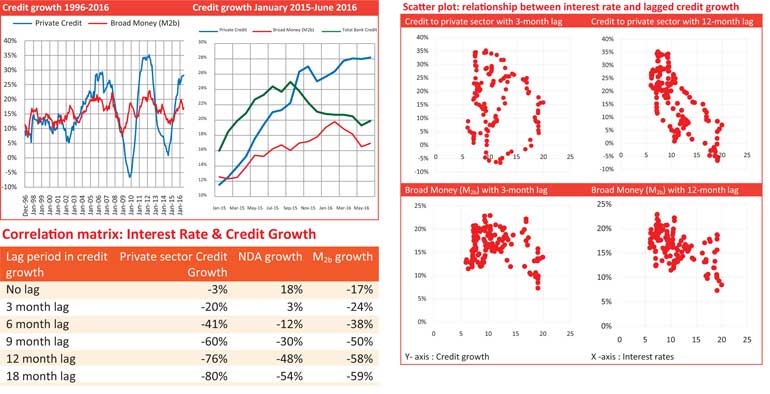

The growth of money supply is monitored by the growth of Broad Money (M2b). The most important parameter of broad money is the credit to the private sector by Licensed Commercial Banks – LCBs. The growth observed in credit to the private sector by LCBs was at a high rate of 28.0% and 28.2% respectively in May and June 2016.

The growth of money supply is monitored by the growth of Broad Money (M2b). The most important parameter of broad money is the credit to the private sector by Licensed Commercial Banks – LCBs. The growth observed in credit to the private sector by LCBs was at a high rate of 28.0% and 28.2% respectively in May and June 2016.

Despite low domestic inflation during 2015, bank credit to the private sector has grown by a staggering 25.1% (year-on-year basis) in December 2015. The trend in the growth of private sector credit continued throughout the year in spite of an increase in policy interest rates and the Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) of the commercial banks. However, the trend in Broad Money (M2b) has been different – the growth of broad money has marginally come down to 17% in June 2016 from December 2015.

Broad Money

Broad Money (M2b) in addition to private sector credit includes two other components - credit to the Government and credit to Government corporations (SOEs). These two components are less sensitive to the level of interest rates prevailing in the economy since the budgetary program drives Government borrowing.

As of December 2015, credit to the private sector accounts for nearly 60% of Broad Money (M2b). In the context of a wider definition of Broad Money (M4), the importance of credit to the private sector by commercial banks significantly reduces as the credit given by Licensed Specialized Banks (LSBs) and Licensed Finance Companies (LFCs) are included in wider definition.

Commercial bank credit to the private sector represented only 45% of Broad Money (M4) by the end of 2015. This indicates that any decision based only on observed growth in private sector credit by commercial banks could be misleading to a certain extent since the behaviour of one component could be different from the aggregate behaviour.

Domestic inflation

The observed upward trend in domestic inflation from January-July 2016 could be a concern for a thoughtful Central Bank. In my previous newspaper column on the subject of monetary policy, the danger of permitting inflation to get entrenched in the economy was highlighted. The concern of the CBSL over domestic inflation is justified. However, the CBSL’s researchers should be able to disaggregate domestic inflation into the components and understand the drives of inflation. The Sri Lankan economy has a disproportionately large non-tradable sector. One key driver of domestic consumer inflation is the price of agricultural products.

The price of those agricultural products fluctuates widely in response to supply shocks due to adverse weather or other disruptions. Sri Lanka has experienced two such disruptions in the recent past: the island-wide flooding and the destruction caused by an explosion at the Salawa military armoury. Although disasters interrupted the supply network, the supply shocks of this nature can result in a spike in consumer inflation though it is not a sustainable increase in price levels - once the supply shock is over, the prices stabilise and consumer inflation recedes to normal levels.

Another cause of domestic consumer inflation in the recent past was the broadening of VAT. Such indirect taxes increase the cost of production that passes on to consumers in general and subsequently could cause a temporary spike in consumer inflation. However, those prices stabilise along with base level change, a one-time price adjustment doesn’t cause a sustained increase in the general consumer price level.

The monetary authorities are highly concerned over demand side inflation due to an overheating economy. Excess growth in money supply creates a sustainable increase in the general consumer price level. If the accommodative policy is continued in such circumstances, it could result in a self-feeding cycle. The temporary price increase due to a mismatch in aggregate demand and supply doesn’t cause a sustainable increase in the general consumer price level.

Lag effect

Monetary policy works within a certain time lag. The impact of the change in the reference interest rates to reflect in the general price level takes about 2-3 quarters. The policy rate changes adopted earlier this year should start showing their impact on the economy now. Before adopting a hawkish mode, the CBSL should have observed the impact of the policy changes adopted earlier this year.

Empirical studies should help in this instance. Empirical research on the lag effect of the monetary policy changes on domestic price inflation is rarely available in the public domain. If the CBSL researchers have conducted such studies, it should help the CBSL make more accurate policy rate decisions

A simple analysis of the correlation between interest rates (12 month Treasury bill rate) and the credit growth during 2003 to June 2016 indicates that the time lag in monetary policy action on the credit growth is about 9-18 months. For example, the correlation between interest rate and credit growth after 12 months is negative 76%. This means the interest rate today explains nearly 76% of the credit growth 12 months later. The impact deepens as time elapses. This indicates that rate hikes early this year should start reflecting in credit growth fully towards only the fourth quarter of the year. However, this analysis is subject to a plethora of statistical errors and one needs to conduct a statistical test to establish its validity.

Cost of monetary policy

The increase in policy rates pushes up the borrowing cost and the cost of conducting business in an economy. Central Banks use policy rates to discourage unwanted borrowers and curtail demand for credit to bring down inflationary pressure. The Government and Government corporations are generally insensitive to the cost of borrowing. Despite the higher interest rates, the Government has to borrow to fulfill its budgetary requirement. Except capital expenditure, a major part of Government expenditure is predetermined and has no space to be curtailed. The Government has committed itself to its stated deficit target this year and the fiscal data of the first half of 2016 indicates that the Government budget is on target. The increase in interest rates due to tight monetary policy this year has increased the interest cost of the Government by nearly Rs. 35 billion-Rs. 40 billion. Though the CBSL is concerned about possible fiscal slippage, the monetary policy through high interest rates has in fact become a major contributor to fiscal slippage.

The conduct of monetary policy by the CBSL under the new Government has been objective and proactive. The recent increase in policy interest rates is seen as costly to the Government under the tight fiscal policy environment although the policy action has prompted fear of fiscal slippage. Though the textbook prescription suggests that increased interest rates help to control inflation, the impact may vary depending on the nature of the economy. Empirical research on the disaggregation of drivers of inflation and the lag effect of monetary policy on credit growth and inflation should be conducted in order to fine-tune the monetary policy decision.

(The writer is a CFA charterholder with local and international capital market experience).