Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 11 April 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

MTI Consulting CEO Hilmy Cader - Pic by Daminda Harsha Perera

A powerful shake up of exporters

In a recent forum and discussion on the country’s exports organised by MTI Consulting and Daily FT in Colombo, MTI Head Hilmy Cader threw a formidable challenge at exporters. He said that the country is doomed if exports do not grow in line with the growth in global trade and the exporters should wake from the deep slumber in which they have been savouring complacently. That was not a traditional ‘wake-up call’. Instead, it was a powerful ‘shake-up’ that leaves them with no alternative. They have to lift themselves and thrust forward if they are to fly high in the world of exports. Cader’s synthesis of the issue is as follows:

Sri Lanka’s dismal record of exports

During the 15 year period from 2000 to 2014, Sri Lanka’s exports have grown only by 2.1 times from $ 5.5 billion in 2000 to $ 11.5 billion in 2014. In fact, if one takes into account the country’s dismal export performance in 2015 at $ 10.5 billion which data were not available to Cader at that time, the growth is pretty dismal with an increase of a little less than even 2 times. In contrast, during 2000-14, Bangladesh had recorded an export growth of 4.7 times and Vietnam, 9.4 times. Because of the slow growth in exports, Sri Lanka’s exports as a share of its GDP had been continuously falling. He said that this was not an achievement about which the country could be happy. That was because imports are growing faster than exports leading to a widened trade gap requiring the country to depend principally on remittances to part-finance the deficit.

Concentration on a few product lines

Cader supported his claim by examining the constituent products in Sri Lanka’s export sector. In the export structure, apparel has been the largest segment accounting for 44% of the country’s exports. When the traditional three-tree products, namely, tea, rubber and coconuts, are added, all four sectors account for 73% of the total exports of the country. The balance 27% representing 24 sectors, according to Cader, had been dispersed among 3100 odd exporters. That composition has not changed much in the 10 year period from 2005 to 2014. The most disturbing observation, according to Cader, has been the zero level contribution by the entrepot trading activities to Sri Lanka’s wealth creation during this period.

Diagnosis of the ailment

Diagnosis of the ailment

Cader had diagnosed several causes for the country’s dismal performance in exports. One is the lack of appropriate scale of operation with more than 3700 exporters contributing small amounts to total export revenue. In fact, the number of exporters who has had an export turnover of $ 100 million had been less than ten. The whole of the agricultural exports has been fragmented over a large number of small players. This factor has inhibited the country’s export growth. Another reason has been Sri Lanka’s low research and development or R&D outlay that had forced the country to carry on what it had been doing for ages. As a result, the basic goods which Sri Lanka has continued to export had generated both low value addition and low returns. Sri Lanka’s high tech exports have been close to 1% of the total merchandise exports; in other emerging countries, they are much higher with 44% in Malaysia, 28% in Vietnam, 20% in Thailand and 8% in India (available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.TECH.MF.ZS ). Though Cader did not highlight, the continued simple product export has enabled Sri Lanka’s competitors to copy technology easily and out-beat Sri Lanka with their low wages.

No ‘hunger’ for a quantum leap

So, according to Cader, Sri Lanka had been exporting simple products to the rest of the world and those simple products have now reached their saturated point. This makes it necessary for Sri Lanka to make a quantum leap – a change that would put Sri Lanka to a completely different level and structure of exports. Cader asked the question openly whether Sri Lanka’s exporters have got the ‘hunger’ for such a quantum leap. His answer was that, except major apparel exporters, the others have not. What is needed in Sri Lanka is to have a group of ‘category invaders’ who could take Sri Lanka to the next level. In 1980s, this was done by the apparel industry, but by now, it too has reached its saturated point. Cader opined that the small and medium industry is hailed by everyone today, but it lacks the needed high scale to take Sri Lanka to the next level. Also, exporters today are also faced with very valid operational issues such as funding, markets, labour costs, unproductive governmental controls etc. They should be resolved for the exporters to maintain the current status. But resolving them alone will not take Sri Lanka’s exports to the next level and that would depend on a number of new policies taken.

The perils of obsession to value addition

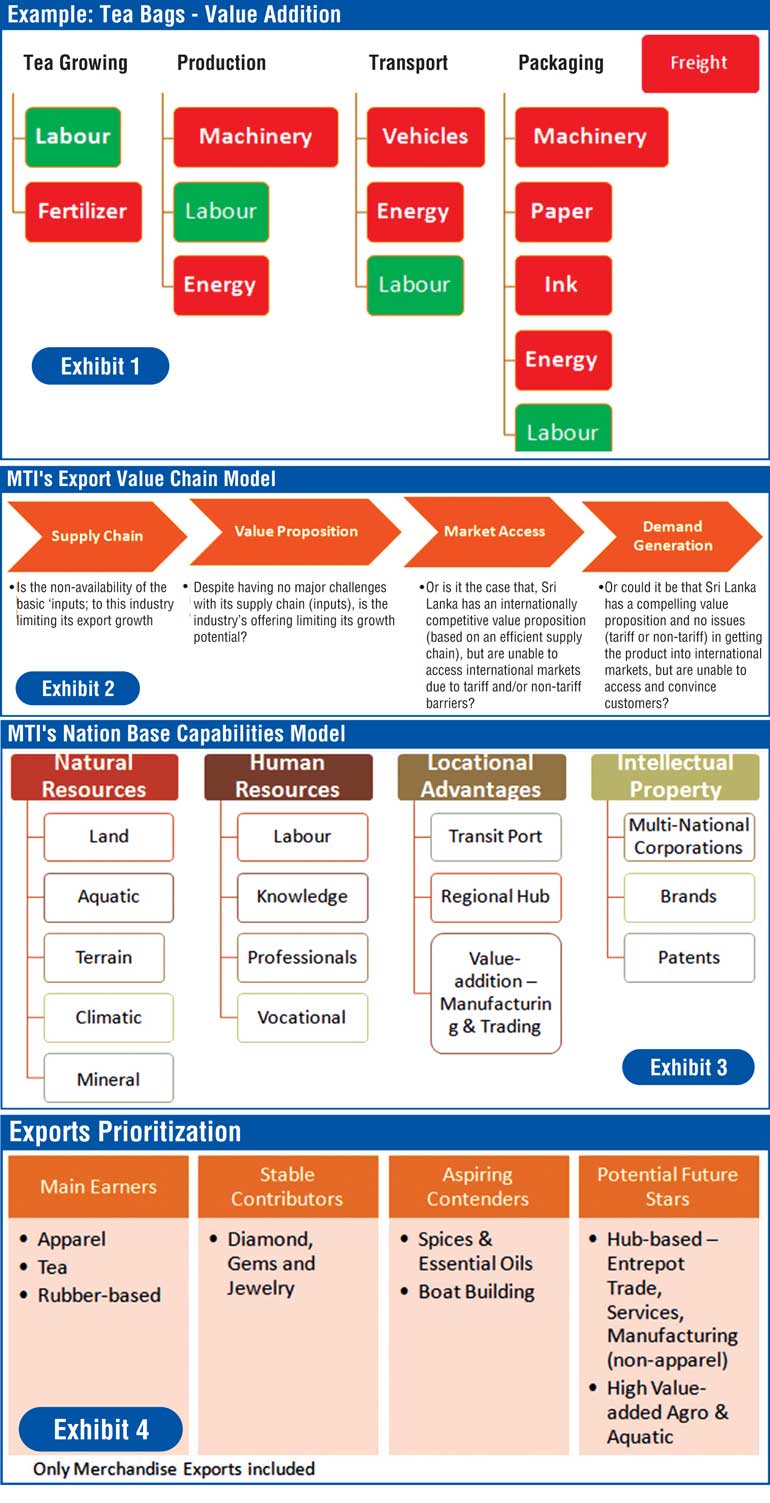

There is an obsession to increase the value addition component in order to increase Sri Lanka’s export earnings. But value additions do not necessarily increase the country’s exports on a sustainable basis. Cader presented the example of tea bag industry to prove his point (See Exhibit 1). There are five stages of the production of tea bags. They are tea-growing, production, transport, packaging and freighting. Of all these five stages, the only value addition is the labour inputs put into the production process. External inputs used in each of these five stages are much more than the labour inputs used for the process. In tea growing, such external inputs consist of the application of fertiliser. In production, the use of machinery and energy; in transports, vehicles and energy; in packaging, machinery, paper, ink and energy; and in freighting, the whole process of shipping tea bags to their intended destinations. If labour costs are cheaper and constitute only a small fraction of the total value, so is the value addition of the tea bag industry. The implication here is whether such small contribution could lift the tea industry from the depth to which it has fallen.

The woes of the tea industry

Cader tried to answer this question by looking deeply at the country’s tea industry. Its current contribution is about $ 1.6 billion with a cumulative annual growth of about 8% over the last ten year period. Sri Lanka’s tea industry is faced with rising costs which have made it totally unviable; as against this background, its competitors have the benefit of lower costs than those in Sri Lanka. Its customer base as well as brand development is highly fragmented allowing no sufficient scales of operation. Worse, it is presented as a generic product called ‘Ceylon Tea’, whose brand name is owned by nobody. To complicate the matters further, R & D outlay across the entire value chain of the tea industry in the country is very low. Cader opined that instead of promoting the brand called Ceylon Tea, Sri Lanka should promote individual brands in tea.

Can Ceylon Tea sustain?

Cader’s diagnosis and prescription here are in line with what this writer has been arguing in the past with respect to the ailments in the country’s tea industry. In an article titled ‘Storm in Sri Lanka’s tea cup: A more pragmatic approach is the key’ (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/87588/Storm-in-Sri-Lanka-s-teacup--A-more-pragmatic-approach-is-key ), this writer argued that some 150 years ago, it was easy for Sri Lanka to promote the brand ‘Ceylon Tea’; even in bill boards in grocery stores in London, Ceylon Tea was projected as a ‘brain tonic’. However, with the name of the country changing from Ceylon to Sri Lanka in early 1970s, the country called Ceylon is no more in the vocabulary of young consumers. Today, the problem would be to explain what Ceylon is: hence, when “it comes to Ceylon tea, one may even tend to think that Ceylon is a part of Sri Lanka going by the references to other teas like Darjeeling Tea (a part of India), Nilgiri Tea (again a part of India) or Cameroon Tea (a part of Malaysia)”.

The need for developing private brand names

Therefore, this writer argued that Sri Lanka’s tea exporters should endeavour to develop their own private brand names. There is an owner of such private brand names and that owner has the incentive to spend money on the development and promotion of that brand name. The brand name Ceylon Tea has no owner and without an owner, there is no one who willing to promote that brand name. Accordingly, this writer argued: “The owner of that public property, presumably the government of Sri Lanka, has no sufficient resources to promote it globally on the scale which such promotions need to be conducted. Even if it has resources, governmental promotional activities are inefficient and ineffective in creating the required impact in consumers compared with promotional campaigns launched by global soft drink manufacturers like Pepsi or Coca Cola”.

Governments are poor in developing country brand names

This writer further argued: “If the government raises funds to finance such promotional campaigns by taxing the industry, the industry has the right to demand for the best results and impact out of such expenditure. But the industry has no say in the way the campaigns are conducted for it would be in the hands of bureaucrats over whom the industry has no control. This would be an unsatisfactory arrangement where one spends money but has no role in deciding its quality and has to accept the final output whether he likes it or not perhaps with some grudging complaints”.

Brand names can address consumer grievances effectively

In modern marketing, to establish brand names, it is necessary to continue with promotional campaigns unceasingly so as to drive the brand name hard into the minds of the prospective consumers. To establish a good brand name, it is essential that the supplier has an effective mechanism to handle consumer complaints and grievances promptly. But, since sellers are numerous under a common brand name, there is no single agency responsible to handle consumer complaints and redress their grievances. Hence, private brand names are more effective than public brand names. So, advice to the tea industry was that it should develop private brand names like Lipton, Brooke Bond, PG Tips and Twine and so on and promote them with personal funds so that in the long run, the particular marketer will benefit. When the local brands become global brands, the country’s tea industry, whether it is Ceylon Tea or Sri Lanka Tea, will benefit.

Should Sri Lanka continue to be only a tea producer?

Tea being a beverage has several competitors, hot drinks like coffee, soft drinks like Coca Cola and Pepsi and light alcoholic drinks like beer. To push tea up in the market as a major drink, it has to be mindful of the changing consumer preferences and the marketing strategies adopted by its competitors. On both counts, Ceylon Tea has lost. Cader has therefore suggested that instead of producing tea, Sri Lanka should now go for tea trading. This is what this writer recommended in the article under reference: “So, there is a hard choice which Sri Lanka has to make in its move toward making tea a $ 2 billion export industry. That is, either increase the volume by importing tea from other countries or wait patiently till the tea prices increase to a level of $ 6 a kg in the market. Even if the tea prices go up to the level required on its own accord, Sri Lanka has to supply teas which the world consumers want to drink and that would mean producing again value-added tea by the country. If Sri Lanka does not do that, others will import valuable Ceylon Tea, blend it with other teas and sell at premium prices thereby denying the benefit to Sri Lanka. Hence, all that is needed today is to shed the emotional bonds and have a more pragmatic approach toward tea by taking into account the emerging global trends in beverages”.

Need for joining supply chains

Cader has recommended that Sri Lanka should join supply chains instead of seeking to produce the whole value of a product locally (See Exhibit 2). This is in terms of the assessment of the capability of Sri Lanka with respect to producing goods and services (See Exhibit 3). In this, an important requirement is for Sri Lanka to develop intellectual property by moving across the borders by becoming multi-national, branding and patenting. It also pre requires Sri Lanka to engage in high R & D to ascertain the values which it can create in the global supply chain as a valuable partner. Cader has therefore warned that the current export business of $ 11 billion or so should not be taken as given. The way forward should be to protect the current export base over the next 2 to 3 year period given the global challenges. Then, the move should be to select major thrusts of export promotion that involves prioritisation as given in Exhibit 4. There, the potential future stars would be hub-based entrepot trading, services, concentration on non-apparel manufacturing, developing high value added agro and aquatic products.

Repeating insanity should be halted

It is indeed a challenge which Cader has thrown at Sri Lanka’s exporters. Their future will depend on taking this challenge and making a quantum leap in export promotion. That would require them to make a complete change of what they do today since, as Cader has quoted a quotation by Albert Einstein, doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results would be sheer insanity.

(W.A Wijewardena, a former Deputy governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected] )