Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 12 November 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

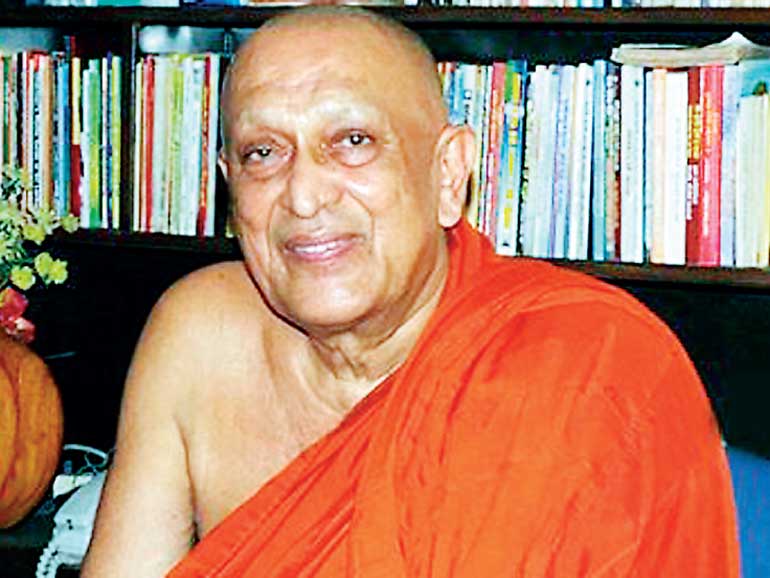

Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero

At the time of his passing, Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero was the nation’s embodiment of political morality. To make rulers righteous  was his life’s mission. He was the exceptional Buddhist monk who sacrificed his own nirvana for the sake of others.

was his life’s mission. He was the exceptional Buddhist monk who sacrificed his own nirvana for the sake of others.

He secured his place in our annals as the prophet who spearheaded the people’s movement for a just society. That was under trying times. At high noon we were groping in the dark. His call to be governed by righteousness has no parallel except of that inscribed in the second rock edict of Ashoka now standing in desolate grandeur between Lumbini and Buddhagaya.

Once his militant profile adorned the jacket cover of the book ‘Buddhism Betrayed’ by the eminent Sri Lankan anthropologist Stanley Thambaiah who explored the role of religion in post-independence politics.

Following 1956, there emerged a proposition that ‘political morality that regulated state-society relations in post-1956 Sri Lanka was in essence Sinhala nationalism.’ That is only half the story.

Sir Walter Hankinson, the first British High Commissioner to Sri Lanka, wrote to London a year after independence: “There have been no startling changes in the domestic political scene; there have been no disturbances among any section of the population; there have been no sudden or sharp alterations in any of the institutions of Government; there have up to the present been no untoward changes in the economic Situation. Nearly all the public institutions, Governmental and others in Ceylon, are based on English models, laid down often many decades ago by the Colonial administration. The result is that an appearance startlingly familiar to English eyes is presented by the political scene. The Cabinet, the House of Representatives, the manner in which Parliamentary business is transacted and relationship of the Civil Service to the political executive all follow the English model. This combined with good relations prevailing between Europeans and Ceylonese has produced an atmosphere in which an English observer feels almost strangely at home.”

That Buddhist monks formed a sizable and significant component of the avant-garde [a stylish contemporary expression] of the movement that brought about the change of 1956 is no accident.

Walpola Rahula Thero with his classic work the ‘Heritage of the Bhikku’ sought the space for the monk as a public leader in place of the ‘ascetic recluse’ a role assigned by the indigenous gentry whose fidelity to the systems of the mother country was so eloquently expressed by Sir Walter Haskinson.

What happened in 1956 is best described by Pieter Keuneman in an article written to the Ceylon Daily News souvenir to commemorate the opening of the new Parliament at Sri Jayewardenepura 29 April 1982. A little more than one year before the pogrom of 1983. “I doubt whether we will ever witness again so moving a spectacle as the people streaming in to Parliament, as they did after the election of 1956, and reverently and affectionately stroking the benches where the members they elect would sit.”

What followed after 1956 was the emergence of the Sangha as a defining political institution. Though eclipsed temporarily following the assassination of the Prime Minister in 1958 it gathered itself as a lever of power when politicians discovered them as movers and shakers in electoral politics in the sixties and seventies. Soon there emerged a UNP Sangha and an SLFP Sangha. That both sides are found weeping in Kotte is a tribute to the departed ‘Bodhisatva’ monk.

It is now fashionable to claim that the introduction of the market economy in 1977 was an economic game changer that radically changed the direction of the nation. Our support of Great Britain on the invasion of the Malvinas islands and the scant attention paid to the massive social disparities created by cold blooded liberalisation indicates that the ideology of the free market economics was a return to the old charming world of Sir Walter Hankinson. That too was a repressive time. Robber barons were welcomed and protesters were bullwhipped. That was when the militant monk received his baptism under fire in the company of Professor Ediriweera Sarathchandra.

The market economy with a human face followed. That it could not wash away its war paint from the Chicago school is another story.

The Sangha institution today is no better and no worse than any of our other public institutions. They have carved a niche as intermediaries in a thriving industry of patronage politics.

That venerable Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero was no part of that grand design was the good fortune of our nation. That is what made him the exceptional leader.

In his bid to repeal the 18th Amendment and scarp the executive presidency he did not find many backers from among his saffron brotherhood. On the contrary he earned the scorn of some firebrand defenders who muddled national sovereignty with a brand of neo fascism. At helm of the National Movement for a Just Society he was as lonely as was Sir Thomas More the martyr and author of Utopia.

Venerable Sobitha Thero in his role as democratic activist remained a committed Budhaputhra. He saw Buddhism as a creed of service to others. By word and deed he followed the ‘Mahawagga’. For more than two years before 8 January he wandered forth for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, in compassion for the world, for the welfare, for the good, for the happiness of gods and men.