Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 27 July 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There is a Sinhala proverb which goes “Thaman hisata thama athamaya sevanala” (It is only one’s hand is the shelter/shadow for one’s head). It highlights what we are going to discuss in today’s column. In the spate of a wide range of human fatalities reported by local media, the Genovese Effect offers rich insights into human behaviour, particularly that of bystanders of an event.

Overview

There is a specific set of behaviours named the Genovese Effect. It is also more widely known as bystander effect. It essentially refers to the phenomenon in which the greater the number of people present, the less likely people are to help a person in distress. When an emergency situation occurs, observers are more likely to take action if there are few or no other witnesses.

In a series of classic studies, researchers Bibb Latane and John Darley found that the amount of time it takes the participant to take action and seek help varies depending on how many other observers are in the room. In one experiment, subjects were placed in one of three treatment conditions: alone in a room, with two other participants or with two confederates who pretended to be normal participants.

As the participants sat filling out questionnaires, smoke began to fill the room. When participants were alone, 75% reported the smoke to the experimenters. In contrast, just 38% of participants in a room with two other people reported the smoke. In the final group, the two confederates in the experiment noted the smoke and then ignored it, which resulted in only 10% of the participants reporting the smoke.

Catherine Genovese

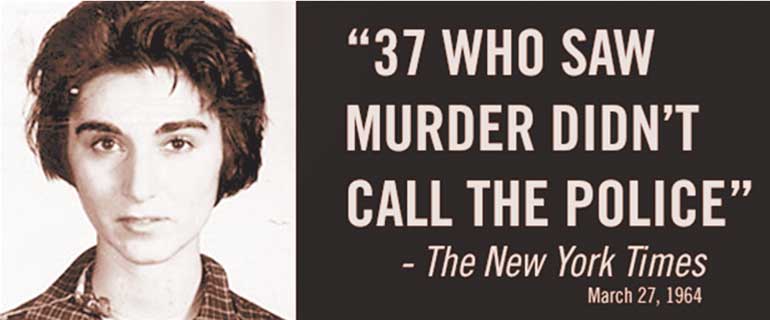

The most frequently cited example of the bystander effect in introductory psychology textbooks is the brutal murder of a young woman named Catherine “Kitty” Genovese. On Friday, 13 March 1964, 28-year-old Genovese was returning home from work. As she approached her apartment entrance, she was attacked and stabbed by a man later identified as Winston Moseley.

Despite Genovese’s repeated calls for help, none of the dozen or so people in the nearby apartment building who heard her cries called police to report the incident. The attack first began at 3:20 a.m., but it was not until 3:50 a.m. that someone first contacted police.

Initially reported in a 1964 New York Times article, the story sensationalised the case and reported a number of factual inaccuracies. While frequently cited in psychology textbooks, an article in the September 2007 issue of American Psychologist concluded that the story is largely misrepresented mostly due to the inaccuracies repeatedly published in newspaper articles and psychology textbooks.

Her true story

It was interesting to note a narration written subsequently as if Kitty was describing the fatal events. It goes as follows:

“I am gone now but my name was Kitty. Kitty Genovese. On 13 March 1964, something terrible happened. I was murdered. But that’s not the most terrible thing that happened, because the kind of murder that occurred haunts humanity still. The reason: Bystander Apathy. People stood by and watched me die. A lot of people. Everyone thought that someone else would help me. But nobody ever did.

“I suppose that the good in any of this, if there is any good at all... is that since 1964, people have studied my death. My murder. People study my murder, not because it is an unsolved case and not because they don’t know the entire details of how I died.

“I had just driven home on the morning of 13 March 1964. The time was in the early morning hours, around 3:15 a.m. I parked about 30 meters (100 feet) from my own apartment door. Winston Moseley approached and startled me and I bolted. He ran after me and caught me, overpowering me, stabbing me twice in the back. I screamed (and someone else saw, too).

“Someone yelled out, ‘Leave that girl alone!’ At this point...I could have survived, I could have lived, because the neighbour who shouted ‘Leave that girl alone!’ had frightened Moseley away. He fled right away. I made my way to where my apartment was at the end of the building, even though I was severely injured, but nobody ever came to check on me, even though they had heard my screams and had seen an attacker. Someone did, however, phone the police, but records show that whatever calls were made over this situation did not receive priority, so still I received no help.

“A witness told later that his father phoned police, giving details as best he could, saying that a woman was being ‘beat up, but got up and staggered around’. Another witness would say that he saw Moseley get into his vehicle and drive away. People told, later on,

that after Moseley was observed getting into his vehicle and leaving the scene – they noticed that he returned about 10 minutes later.

“At this point, since people were quite aware of Moseley’s return and were obviously watching out windows, my life still could have been saved... Moseley returned to kill me. And nobody acted to help me when they could. Moseley returned to methodically search the area, including the parking lot and train station, and the immediate apartment complex area.

“I had managed to get into the hallway, at the back of the building before Moseley found me. He re-launched a fresh attack, beating and stabbing me several more times. I tried to fight, but this only meant that my hands got cut up, and as I lay bleeding, Moseley sexually assaulted me, then stole my money (about $49) before he again fled from the scene.

“The assaults were not quick-as-a-flash – they spanned about a half-hour’s time frame, and by the end, I lay beaten, robbed, cut and bleeding – dying. Karl Ross phoned the police minutes after Moseley’s last attack, and finally, police responded to Karl Ross’ phone call, arriving a few minutes afterward, along with medical help. The attacks were too much. I died as they transported me to the hospital.

“Later on, the Media (The Times) would report that 38 witnesses heard or saw something related to my death, however, this part was over-exaggerated by the media. Still, about a dozen people did see and hear what went on – or at least portions of the attacks. Only one witness, Joseph Fink, claims to have been aware that I was actually stabbed during Moseley’s first attack, and only one witness, Karl Ross, claims to have been sure that I was stabbed during the second and final attack.

“Many people who heard noises that they couldn’t quite name, believed that what they were hearing was a lover’s spat or some kind of domestic argument going on. (Yet – it wasn’t thought of as serious.) Some thought they heard what was a drunken brawl or a bunch of drunken, noisy friends leaving a bar. Later on, Moseley confessed to killing me, and also confessed to killing two other people. I wonder if neighbours heard something when those other two people were killed by Moseley.”

Why it happens

According to Kendra Cherry, there are two major factors that contribute to the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility. Because there are other observers, individuals do not feel as much pressure to take action, since the responsibility to take action is thought to be shared among all of those present.

The second reason is the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways. When other observers fail to react, individuals often take this as a signal that a response is not needed or not appropriate. Other researchers have found that onlookers are less likely to intervene if the situation is ambiguous.

In the case of Kitty Genovese, many of the 38 witnesses reported that they believed that they were witnessing a “lover’s quarrel,” and did not realise that the young woman was actually being murdered.

Lessons for us

Sri Lanka is supposed to be more collectivistic compared to some Western countries where individualistic approach is the more dominant. There could also be a Sri Lankan twist to the whole issue where the bystanders are aware of the consequents of harassment, waste of time and even threats to their lives if they come forward.

There were encouraging responses in the recent past in this context. Police managed to arrest a couple of culprits based on timely tips by the “bystanders”, in stark contrast to bystander effect. The challenge is to sustain such practices where a gradual decline of concern for others, fuelled by over-emphasis on materialistic gains is evident.

The practice of socio-cultural and religious values with regards to being concerned about ones’ neighbour is the vital need. It is for managers and others alike, a wakeup call to be more conscious about the fellow human beings.

(Dr. Ajantha Dharmasiri is the Chairman and Director of the Board of Management of the Postgraduate Institute of Management (PIM). He also serves as an Adjunct Professor in the Division of Management and Entrepreneurship, Price College of Business, University of Oklahoma, USA.)