Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 5 May 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

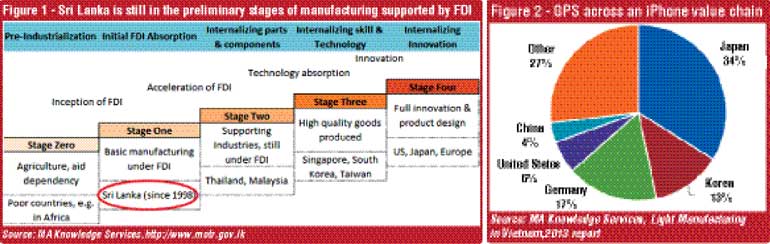

The world is at the tipping point of a manufacturing change where ground-breaking technologies, such as 3D printing and cloud computing, could soon alter the entire manufacturing landscape. However, their potential for Sri Lanka is less relevant as the country continues to lag its peers in terms of executing High Value Manufacturing (HVM) processes. Combining a good entry point using Global Production Sharing (GPS), reinforcing the country’s SME pillars via clustering, and identifying its competitive niche, may help it move up the manufacturing value chain.

The world is at the tipping point of a manufacturing change where ground-breaking technologies, such as 3D printing and cloud computing, could soon alter the entire manufacturing landscape. However, their potential for Sri Lanka is less relevant as the country continues to lag its peers in terms of executing High Value Manufacturing (HVM) processes. Combining a good entry point using Global Production Sharing (GPS), reinforcing the country’s SME pillars via clustering, and identifying its competitive niche, may help it move up the manufacturing value chain.

Sri Lanka was ranked 115th (among 185 countries) in manufacturing complexity, with an Economic Complexity Index (ECI; holistic measure of the production characteristics of large economic systems) of -0.87. In comparison, Malaysia ranked 23rd (ECI of 1.15), Thailand 32nd (0.77) and Vietnam 93rd (-0.58).

Malaysia has a considerably higher ECI because it possesses a complex, interleaved network within the electronics and machinery and equipment (M&E) manufacturing sector; the sector encompasses a larger diversity of related, high value products relative to Sri Lanka’s reasonably developed, yet low-value-added apparel sector. Vietnam and Thailand appear to be in between, moving away from the low value added apparel sector, to the more complex electronics and M&E sector.

In comparison, Sri Lanka’s high value sectors are plagued by weak industry links and a lack of integration across its highly fragmented SME base. Furthermore, insufficient backward linkages in Export Processing Zones (EPZ) to domestic industries (even in its established apparel sector) result in inefficient supply chains.

Malaysia progressed to complex manufacturing processes by horizontally transferring its knowledge to sectors with similar manufacturing processes. For instance, by using its expertise gained from manufacturing old-school peripheral products in the 1990s (such as sound recorders, storage disks and tapes), Malaysia moved to new, higher-value products such as oscilloscopes, spectrum analysers and other precision instrumentation equipment.

Similarly, Vietnam is gradually maturing away from final assembly for high-tech firms (such as Samsung and Canon) towards processes more inclined to product design, leveraging the expertise gained from its strategic FDIs. In contrast, Sri Lanka continues to focus on low-value added manufacturing work.

If Sri Lanka wants to move up the manufacturing chain, then it needs to start exploring viable opportunities that serve as an entry  point. The most likely strategy would be through GPS, which will enable it to assimilate the technology of more advanced peers.

point. The most likely strategy would be through GPS, which will enable it to assimilate the technology of more advanced peers.

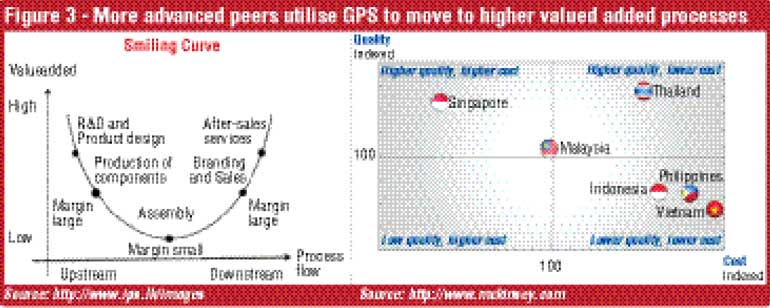

Simply put, GPS is the manufacturing strategy in which a product’s value chain is split into smaller processes, often located in different geographies. Thus, it allows countries, such as ours, to enter into basic manufacturing processes of complex products. GPS enables an economy to identify and focus on its key competitive advantage and gradually specialise in certain aspects of a product’s value chain. This can then be optimally leveraged to expand across the particular value chain or to similarly complex products, adding value to the manufacturing process.

As a result of the discussed benefits, GPS trade as a percentage of total trade increased by more than 30ppt over 1988-2013 in developing economies. However, Sri Lanka’s participation remains minimal, at just 6% of value added in the parts, components and final assembly section of a typical product’s value chain. Comparatively, Malaysia and Thailand contribute around 70%.

Thus, it is essential that Sri Lanka begins significant participation in the GPS of HVM activities, even if they are not of the highest value processes at first.

After achieving sufficient GPS in manufacturing industries, Sri Lanka has to streamline its R&D and integrate supply chains to ensure maximum efficiency in the process. The time-tested measures of clustering and establishing EPZs will give it the most fertile soil to create such linkages. Clustering a conglomerates’ entire product value chain in a regionally compact area will promote interlinkages, knowledge flow, and efficiency gains via supply chain management and assimilation from more advanced economies. Moreover, self-contained value chains are highly attractive to foreign investors as they also offer higher IP protection (in Sri Lanka, over 80% of EPZ investment was from FDI in 2012).

The benefits of clustering are visible in Sri Lanka. ‘The Competitiveness Programme’ (TCP) was a successful project setup by USAID to drive competiveness via export-oriented clustering. After TCP’s initiation, the cluster increased its exports by 62% between 2001 and 2006, a 35ppt improvement over the prior five years. Moreover, according to McKinsey’s ASEAN economic community research, greater integration via clustering and EPZs can produce productivity benefits worth up to 20%, on average, of the cost base. Other benefits include SKU rationalisation and lower inventory obsolescence that can further yield benefits of 5-15% of the total cost base.

For Sri Lanka to progress to the final ‘innovation’ stage of manufacturing, it must identify niche products and services that drive differentiation. Take, for example, the local electronics assembly industry. The country predominantly manufactures and assembles boards and panels, electrical wiring, transformers, and on a smaller scale, sensors. It can use its expertise in these areas and move ‘horizontally’ to develop sensors for Internet of Things (IoT)specific designs, especially concentrated in areas that are relevant for industrialising developing markets.

In 2016, an IoT solution developed by the University of Colombo’s department of Computing and Sweden’s Uppsala University, displayed capabilities of a ‘Smart fence’ and an ‘Infrasonic elephant localisation system’ that enables farmers to protect crops from wild animals. This is an archetypal practical application of sensor technology being utilised to serve a specialised niche market.

In summary, Sri Lanka’s success hinges on it effectively executing a strategic approach of integrating its SMEs, upskilling its labour force, and identifying key niches in which to outcompete peers. GPS will likely serve as its pillar for achieving this, though Government coordination and support is essential. With all the required elements in place, Sri Lanka should be well on the road to achieving successful high value manufacturing.

(Gamika Seneviratne is an Associate Vice President – Investment Research at Moody’s Analytics Knowledge Services.)