Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Monday, 20 June 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

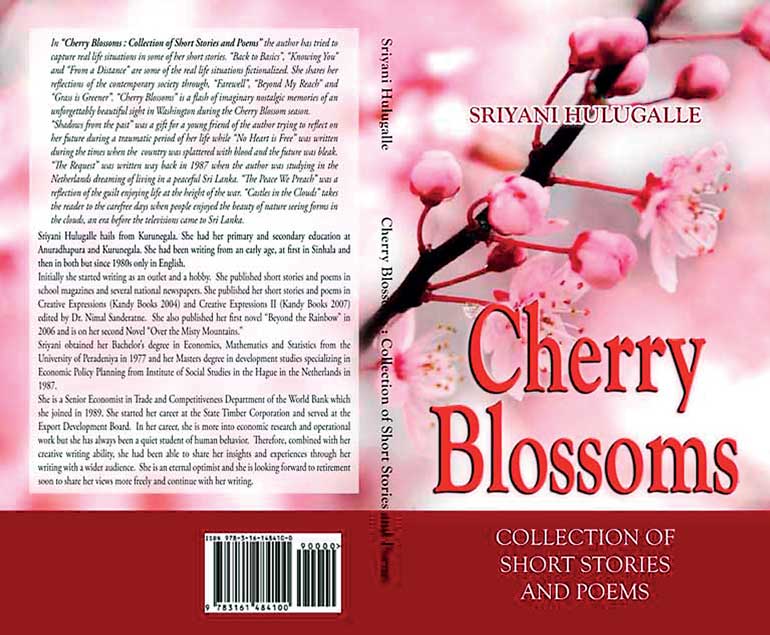

The cover of Sriyani Hulugalle’s collection of short stories and poems ‘Cherry Blossoms’

An economist becoming a creative writer

An economist becoming a creative writer

Economists are known for being heartless because they practise a ‘dismal science’. The story is that, say, when the whole world cries for free goods, an economist would stand up and advise not to give them free.

On many occasions, when the dance is going at high tempo, it is the economist who will pull the ‘punch bowl’ to the immense annoyance of the dancers. They would come up with a lot of theories and laws to substantiate what they say. These theories and laws are drawn from Nature and therefore they should naturally be close to human instincts. But the language they use to present themselves to people is so strange that what they say would become alien to many. Hence, when an economist pens something or opens his mouth, he is naturally placed at the receiving end by society.

In this strange world, Sriyani Hulugalle, an economist attached to the World Bank, has shown that an economist could also be a different species. In her latest collection of short stories and poems, ‘Cherry Blossoms’, she has gone into the depth of human hearts and intricate relationships to bring out another truth in economics. That is, rewards and punishments are distributed among people according to what they do or how they approach problems. The beauty is that Sriyani Hulugalle uses a poetic language to convey her message.

The holistic view from the top of the mountain

When a person gathers experience, he matures gaining capacity to have a holistic outlook of the world. This is pretty much relevant to economists who are said to be climbing to the top of a mountain as they mature.

At the top of the mountain, they see everything below from a holistic perspective. Their vision is wide and they see the world differently from those below. They do not assign values to what they see around them but observe how interactions would bring different outcomes. Those different outcomes are also not valued because with new interactions, they too would bring new outcomes. For them, the world is in a continuous flux – never coming to a resting place and changing from one scenario to another.

Looking at them as independent observers from a mountain top enables economists to cultivate a mental state known as equanimity. This is what Sriyani Hulugalle, the matured economist, has done in her stories and poems in ‘Cherry Blossoms’.

Social conflicts too germinate seeds for creative work

Cherry Blossoms contains 25 pieces of creative work – 13 short stories and 12 pieces of poetry. They have been written over a decade dating back to around 2008. This is the most gruesome period in Sri Lanka’s recent history filled with suspicion, hatred and anger expressed by one to another.

On the flip side, it also provides fertile ground for writers to dig for human miseries and agonies buried underneath. Sriyani Hulugalle too has used the opportunity liberally to bring out her own reading of the events that have gone by during this period.

Thus, some of the stories and poems in the collection take their plot from the ethnic war that cost both parties in the conflict dearly. The characters in her stories relating to war episodes are all human beings who had been dragged into the conflict by outside forces over which they had no control. When one looks at them from the top of the mountain, one would see the operation of the cause and effect law trapping them in a vicious circle from which there is no escape.

Hearts becoming heavy with guilt

Hearts becoming heavy with guilt

The story ‘No Heart is Free’ is wound around a Tamil youth whose parents and younger sister perished in the war in a shootout with the army. That is the most immediate cause that leads to a series of subsequent causes and effects.

Raju, the Tamil youth, is assigned by the movement with the mission of spying on a high ranking army officer living in Colombo. The movement has decided to bump him off because he had been in the frontline of the war against it.

Raju willingly undertakes the mission because he too has a score to settle with the army. Posing as an accountancy student, he comes to stay in an upstairs room that gives a good view of the house next door where the army official lives with his family. In the course of his spying mission, he develops a fraternal bond with the little daughter of the army officer who starts to fill the gap in him left by his dead sister.

A tour of duty that ends in repent

Hulugalle develops the story step by step building affinity with the main characters – Raju, little girl Neesha, her mother and the army officer. All these people who play the game from different sides have been projected by her as human beings with a heart, feelings and a sense of guilt.

Point by point when Raju comes closer to the family, he becomes disillusioned about his mission. He had rated them as enemies before and expected them to return the same. But the wife of the army officer corrects him pretty soon.

She tells him: “This is not a war. War is between two countries. In this conflict, every time a person dies here or there, it is one of the citizens of the country.” Raju is taken aback by this unexpected remark. He asks in return whether or not she hates them. The reply comes straight. She tells him that they are not to be hated because they have been misguided. She prays for peace and reveals to him that her husband too is not fighting a war. He too is anxiously waiting for peace.

A terrorist with a heart

Raju’s mind starts changing but by that time, things have set themselves on a course that could not be reversed. He has given vital information on the daily movement of the army officer to the movement to enable them to eliminate its target.

The dramatic moment arrives as portrayed by Hulugalle. The little girl goes to school accompanied by her father making it an easy target to bump them both in a single operation. Raju’s disillusion rises to the highest point because he did not expect the movement to kill the little girl.

Hulugalle pens it in poetic language: “.....he walked up to Niru who sat exhausted after weeping for hours. Her hair was disheveled and the eyes were swollen. The usually smiley face was lined with sorrow. He could not look at her. As she sat by her side, she in a low hoarse voice muttered, ‘Raju, my Neesha wanted to show you her dress before she went to school. She loved you so much… May be she was your sister in her last birth’ Raju could not control himself and started sobbing.”

The fatal confrontation with the terrorist leader

He storms the office of the city operator of the movement and angrily announces his quitting the movement at the risk of sacrificing his life for justice which is alien to the movement.

He is executed by the movement but he did not care about it. The final moment of his life is dramatised by Hulugalle making readers Raju’s fans. “Raju could see Neesha walking toward him, with a smile. Then, there was a peel of gun shots and he staggered forward. He did not feel the pain but he felt a numbness creeping through his body. As he crashed on to the floor, he saw Neesha smiling and holding the bunch of red roses towards him. He heard her saying ‘Thank you, Raju uncle…I love you’. Raju closed his eyes and let out his last breath with a happy smile adoring his lips.”

Thus, for Hulugalle, men and women who have been unwittingly dragged into the conflict have not lost traces of humanity within them.

Hulugalle’s plea: Don’t shed blood all over

The poem ‘A Request’ has been penned by Hulugalle on the same war theme. It had been written in 1987 when the ethnic conflict was at its early stage. She finds that the two warring parties do not speak each other’s language. Hence, they cannot communicate.

Instead, both parties have taken to guns to speak the language of bullets. The result? Blood is shed all over the Paradise Island. The protagonist, a Sinhalese, prays for peace in a temple carrying a lotus flower in her joint hands. She demands the other party not to divide the country. She opines that both sides should keep the guns away and be united in a single nation.

This poem has captured only one segment of the cause and effect process. It does not seek to understand why the other party has taken to arms. What guns have been aimed at them – physical, cultural or racial – beforehand provoking them to reply with guns? That has not been examined because it had been written, according to Hulugalle, in reply to a propaganda piece spread by the other party upholding the armed struggle.

Lost love of young people

The other stories in Hulugalle’s collection focus on intricate family relationships and romantic love stories which are mostly missed opportunities. A young girl or a boy falls in love with someone attractive in the opposite sex, makes all the plans for a life together but fails to reach the intended goal because of some external influence that suddenly comes in between.

They lead their separate lives after making painful adjustments but cross their path again many years later. At that time, the old flame of love starts to spark again sending them to a temporary solace. To an ordinary reader, this may appear to be a common occurrence but what is important here is how Hulugalle has presented the plot in the story. That is where creativity outshines the common feature involved in the story.

The newly-ignited love of ‘Cherry Blossoms’

The main story ‘Cherry Blossoms’ is about a sudden encounter which a Sri Lankan girl studying in the States for a higher degree has with a handsome young Indian boy. The girl visits a flower garden to savour in the cherries that blossom heralding the arrival of Spring.

Both cherries and the Spring are ideal combinations to breed romance. The girl is all alone away from home and is ripe for a romantic relationship. The boy is young, energetic, dynamic and active and a suitable candidate for such a romance. He crashes into a photo which the girl poses with cherries standing behind the girl uninvited.

The story begins, many years later, when the girl’s younger sister makes a chance discovery of the photo with the boy and makes a comment on the handsomeness of the boy. It takes the girl back to the actual incident. Hulugalle’s narration makes the reader live in the incident: “She came face to face with a tall, astonishingly handsome young man dressed in faded jeans, a striped blue shirt and a midnight blue sleeveless cardigan over it. He also had a camera slung over one shoulder and he had a broad smile adorning his face. With a twinkle in his eyes, he watched her reaction. Then, he put his hands together in an oriental fashion…..She could not resist smiling back him as he had a very friendly smile.”

This sudden encounter sparks flames of on the spot love in the boy but not in the girl. His attempt at getting her contact details or subsequent communications fails.

But many years later, they meet again in Sri Lanka at an international conference where both the boy and the girl present papers. The old love flame ignites in the heart of the boy who confesses that he remained unmarried despite many proposals that had been brought for him by his Mother. The reason? He could not take out from his mind the first love seed that was planted in him at the garden when cherries had begun to blossom. Now they are together and ready to make amends for the lost opportunity. This is an ordinary romantic story, but Hulugalle has developed it step by step retaining the interest of the reader to the end.

The stories ‘Too Late for Regrets’ and ‘Till we Meet Again’ are also written on the same theme of lost love in young age and meeting again later in life to take stock of where they have gone wrong.

Grass is not always greener

The story ‘Grass is Greener’ is on a different theme. It exhibits the concept which the economists call ‘utility’: One tends to give a higher value to things which one does not have and lower value to which one has.

The story is wound around children in the rich family and in the poor family where the mother of the poor family does household errands for the rich family. The rich family has a crippled child in a wheelchair where she had been showered with all the luxuries of modern world. The poor family has children who can freely run around but without food, clothes and shelter.

The crippled child is attracted by the freedom which the poor children enjoy to move about happily; the poor children feel envy about the rich luxuries which the rich girl, though crippled, is having. They think of exchanging places. Hulugalle has presented an economic truth in the form of a moving story.

Hulugalle has presented an important piece of poetry at the end of her collection.

That piece says goodbye to one of the great human beings who was a beacon in the central bank while he was living. Hulugalle’s friend and a colleague of this writer, reputed economist Uthum Herat left this world at a young age leaving a vacuum that cannot be filled easily.

Hulugalle has presented her sorrow and grief about his sudden demise in a moving piece of poetry.

Cherry Blossoms is a good collection of short stories and poetical work. Those who enjoy savouring creative work can enjoy this collection immensely.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])