Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 15 November 2016 00:17 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the background of revenue mobilisation constraints and emerging public debt sustainability risks, curtailment of the budget deficit is inevitable. Hence, Budget 2017 had to be framed in line with the IMF-supported program focusing on fiscal consolidation, as I predicted in my pre-budget commentary which appeared in this newspaper. The Budget, themed ‘Accelerating Growth with Social Inclusion’, envisages a sustained path of fiscal consolidation aiming at a reduced budget deficit of 4.6% of GDP and a lower debt to GDP ratio of 75% for 2017.

In the background of revenue mobilisation constraints and emerging public debt sustainability risks, curtailment of the budget deficit is inevitable. Hence, Budget 2017 had to be framed in line with the IMF-supported program focusing on fiscal consolidation, as I predicted in my pre-budget commentary which appeared in this newspaper. The Budget, themed ‘Accelerating Growth with Social Inclusion’, envisages a sustained path of fiscal consolidation aiming at a reduced budget deficit of 4.6% of GDP and a lower debt to GDP ratio of 75% for 2017.

While raising tax revenue to pursue the daunting task of deficit reduction, the Government has not overlooked offering some concessions to meet people’s expectations, though their effectiveness is debatable. Accordingly, maximum prices of selected consumer goods are reduced and free tabs are to be issued to A/L students. Fiscal incentives have been granted to certain production activities including agriculture and fisheries and small- and medium-scale enterprises. Increased allocation in the Budget for science, technology and innovation is noteworthy, considering their vitality in evolving a knowledge-based economy.

Fiscal policy for inclusive growth in theory and practice

By definition, inclusive growth is economic growth that creates opportunity for all segments of the population and distributes the dividends of increased prosperity, both in monetary and non-monetary terms, fairly across society. In Sri Lanka income inequality is widening between different segments of the population. The richest 20% of households receive as much as 53% of total household income whereas the poorest 20% of households have a meagre income share of less than 5%. Around 40% of the population lives below the poverty line of $ 2 per day, and spatially this is much higher in many under-served areas. Inclusive growth is not only about money income but encompasses various other dimensions of quality of life including child nutrition, healthcare, education, housing, transport and employment opportunities.

Fiscal policy is a key tool that can be used to drive inclusive growth. The tax system has to be progressive, levying a higher percentage of taxes on high income earners so that resources can be ploughed back to meet the needs of the poor.

In this sense, income tax is considered a progressive tax whereas sales taxes, such as the Value Added Tax (VAT), are regressive. Meanwhile, Government expenditure for healthcare, education and social protection can provide better opportunities for all.

In practice, however, the formidable challenge is how to use fiscal policy adjustments to make growth inclusive while ensuring fiscal sustainability.

Moving towards fiscal consolidation

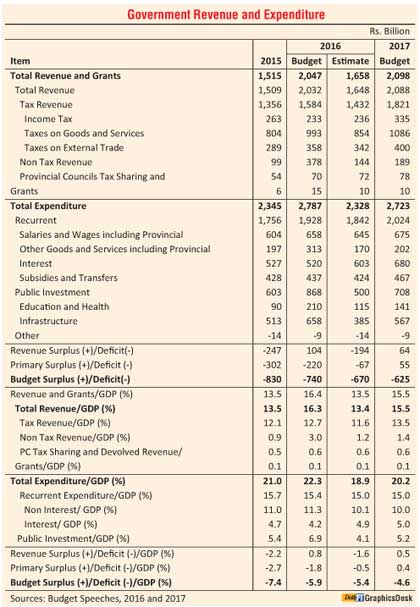

Fiscal consolidation is a key component of the three-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement entered into with the IMF last June. It aims to provide a policy anchor for macroeconomic stability and structural reforms. Fiscal consolidation is to be achieved mainly through increased revenue mobilisation. The Government has been able to fulfill the fiscal consolidation commitments to a large extent by reducing the budget deficit from 7.4% of GDP in 2015 to 5.4% of GDP in 2016, as stipulated in the EFF agreement (Table).

Fiscal consolidation is a key component of the three-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement entered into with the IMF last June. It aims to provide a policy anchor for macroeconomic stability and structural reforms. Fiscal consolidation is to be achieved mainly through increased revenue mobilisation. The Government has been able to fulfill the fiscal consolidation commitments to a large extent by reducing the budget deficit from 7.4% of GDP in 2015 to 5.4% of GDP in 2016, as stipulated in the EFF agreement (Table).

This was achieved mainly by a 9.4% increase in indirect tax revenue. However, the total revenue and grants realised this year, amounting to Rs. 1,658 billion, was well below the amount of Rs. 2,047 billion anticipated in Budget 2016. This revenue shortfall reflects the administrative hiccups encountered in implementing the upward revisions of VAT.

The possible negative impact of the revenue shortfall on the budget deficit was offset largely by cutting down public investment for infrastructure, health and education from the budgeted amount of Rs. 868 billion to Rs. 500 billion in 2016.

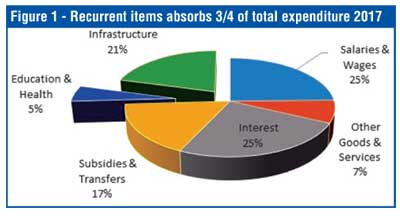

Public investment allocated in Budget 2017, amounting to Rs. 708 billion, is lower than the amount allocated in the previous Budget. There is no fiscal space to increase public investment as around three-fourths of the total expenditure is allocated for recurrent expenditure items consisting of interest payments, salaries, subsidies and other goods and services (Figure 1).

Public investment in health and education is instrumental in developing human capital. Also, public investment induces private investment by means of providing improved infrastructure facilities. Hence, curtailment of public investment has negative effects on economic growth.

Fiscal consolidation relies on indirect taxes

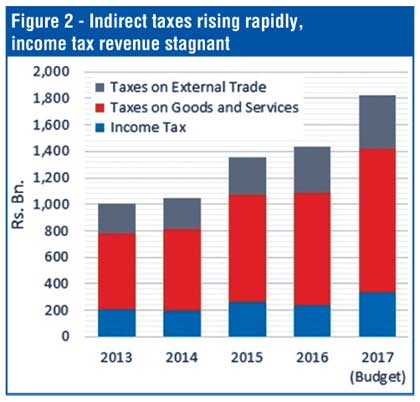

The share of indirect tax revenue increased from 81% in 2015 to 84% in 2016, reflecting a corresponding decline in the share of income taxes from 19% to 16%. The total collection of income taxes fell by 10.3% from Rs. 263 billion in 2015 to Rs. 236 billion in 2016 (Figure 2).

The income tax collection is projected to increase by 42% in 2017 to reach Rs. 335 billion and accordingly the share of income taxes is expected to rise from 16% in 2016 to 18% in 2017.

However, this target seems to be unrealisable given the downfall of income tax receipts this year. Although it is claimed in the Budget that the falling share of direct tax (income tax) is set to increase from 1.9% of GDP in 2016 to 2.9% of GDP by 2020, the ways and means to achieve such improvement are not spelt out.

Prior to the Budget, the VAT rate had been raised from 11% to 15% effective from 1 November. The VAT base also has been broadened to cover certain previously exempted items including milk powder, electric and electronic items, cigarettes, liquor, perfumes, jewellery and coal. Lease or rent of residential accommodation, telecommunication services and healthcare services are subject to VAT now.

The Government anticipates that the VAT revisions will bring a revenue boost of about Rs. 100 billion from the present level of Rs. 280 billion to Rs. 380 billion by next year.

In addition, the indirect tax revisions proposed in the Budget are expected to generate Rs. 55 billion next year, thus gaining an additional revenue increase of Rs. 155 billion from indirect taxes. In contrast, the anticipated revenue increase on account of direct tax proposals in Budget 2017 (revisions of corporate tax, PAYE tax and withholding tax and the new Capital Gains Tax) is only Rs. 65 billion.

Heavy revenue losses from tax incentives for big investors

Since the liberalisation of the economy in 1977, successive governments have granted various forms of tax incentives with a view to attract Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs). They include corporate tax holidays, import duty exemptions and tax concessions for dividends. Both the Board of Investment (BOI) and the Inland Revenue Department grant such concessions.

Based on rough estimates, the revenue loss on account of tax incentives is around 1.35% of GDP which amounts to Rs. 165 billion. This is more or less equal to the annual corporate tax collection. These revenue losses are a major factor that has led to reduce the direct tax component of the country.

The effectiveness of the tax incentives is questionable in the context of low FDI inflows which are still less than $ 1 billion per annum as against the worker remittances amounting to $ 7 billion a year.

In Sri Lanka there is no formal mechanism to assess the benefits of the tax incentives or to estimate the foregone revenue losses. Incentive schemes and their costs are not transparent. The low mobilisation of corporate taxes reflects that the incentive-receiving sectors do not contribute sufficiently to Government coffers to offset the revenue losses. Tax incentives do not necessarily attract FDIs as there are many other determining factors including macroeconomic stability, productivity, competitiveness and infrastructure in the host country.

‘Off-budget’ tax incentives for Port City project

More recently, the Port City project has been granted significant tax incentives, including 25 years of exemptions from corporate tax income, tax on dividends and VAT on construction, in terms of an Extraordinary Gazette Notification issued in September. The Chinese company involved in the project is exempted also from Pay As You Earn (PAYE) tax, ports and airport development levy, CESS, Nation Building Tax and Customs Duty.

The revenue losses to be incurred by the Government for 25 years will be enormous considering the potential of this mega project to generate substantial profits and dividends in the time to come. Such revenue losses have to be compensated by raising taxes applicable to other sectors of the economy so as to ensure fiscal sustainability in the future.

Fiscal constraints on inclusive growth

Certain major fiscal policy decisions adopted from time to time do not come under the purview of annual budgets. The increase in the VAT and the generous tax incentives granted to the Port City project are two recent ‘off-budget’ examples. This weakens the fiscal policy formulation making it difficult to focus on broader economic goals such as growth acceleration with social inclusion, which happens to be the theme of the present Budget. Taking into account the adverse macroeconomic implications of persistent budget deficits, the ongoing fiscal consolidation is inevitable for economic growth and stability. Given the problems of narrow income tax base, tax evasion and generous tax incentives, the income tax collection has remained stagnant and as a result indirect taxes have been used as a convenient tool for fiscal consolidation purposes. Budget 2017 too gives higher weightage to raise indirect taxes.

The excessive dependence on indirect taxes for revenue generation makes the tax system more regressive, hurting the poor and further widening income inequality. Inflationary effects of indirect taxes and the consequent repercussions on the poor also cannot be underestimated. On the expenditure side, limited leeway available to raise public investment in the Budget dampens economic growth, leaving aside inclusive growth.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage, an economist, academic and former central banker, can be contacted at [email protected])