Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Friday, 12 May 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Laksiri Fernando

By Laksiri Fernando

There is no point in allowing the SAITM issue to continue for so long without a solution. The Government or the country should be able to resolve such problems within a reasonable time, let us say two months. The failure to do so, not good for the country and its normal functioning, and much desired development. This is not to say that resolving such a problem is easy. But most difficulties are related to (1) the reluctance to give in (2) unwillingness to face reality (3) hesitation to change previously-held views and (4) acrimonious political confrontations.

At present, the confrontation seems to be mainly between the Government, or certain sections of the Government and the GMOA (General Medical Officers’ Association), although there are several other stakeholders. SAITM (South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine) seems to have taken a back seat, tactfully or not, and their medical students have become the main victims of the situation.

I have seen over 50 articles on the subject in various newspapers and websites, the authors mostly expressing their views ‘for’ or ‘against’ SAITM based on their ideological/political views and/or self-interests. On both counts, the reasoning could be considered ‘subjective,’ which is something not easy to avoid even in my case.

Dr. Ruwan Weerasinghe commendably analysed most of these views (‘To SAITM or Not to SAITM – Is that the Question?’ – Colombo Telegraph, 11 April), listing them into 12 issues, for the discerning readers to make their own judgement/s. Unfortunately, even the present controversy seems to be broadly, ‘To SAITM or Not to SAITM?’ In Weerasinghe’s view, which I largely agree, the rational question instead should be: “Can medical education be provided by the private sector?”

There have been various other articles, some addressing the professional or economic/business aspects of the issue/s, nevertheless finally expressing personal/ideological preferences. Two of the important ones were by Professor R.P. Gunewardene and Dr. W. A. Wijewardena. These are my selections.

Whatever his personal views on the matter of private medical education, Gunewardene (‘SAITM Issue: A Rational Approach Needed,’ CT, 24 February) has frankly noted the following, in respect of negligence or breach on the part of SAITM and also correctly blaming the other authorities, for the present crisis.

“It is regrettable to note that SAITM on their part has continuously disregarded the guidelines issued by the regulatory bodies in their development process. Their gross negligence towards the stipulated guidelines is clearly evident as reported by Professor Carlo Fonseka. In addition, SAITM authorities have not explained the current status of their degree program to the students at the time of admission. It is rather unfortunate that no action has been taken by the appropriate authorities well in advance to avoid the present situation.”

Wijewardena, on the other hand, was highlighting the economic/business aspects of the matter in fact even endorsing private medical education emphasising the “failure of the Government to meet the aspirations of all students seeking to continue for a medical degree at a State university”. Writing after the Court of Appeal decision, favouring the request of students (31 January), nevertheless he was not completely dismissing the institutional criticisms of SAITM by the GMOA or the Padeniya Report. That is why he was talking about “SAITM and private medical schools: One bad start should not lead to throwing away a good idea’ (Daily FT, 20 February). One instance of his acceptance of institutional criticisms is the following:

“According to the correspondence between SAITM’s founder Dr. Neville Fernando and SLMC and between BOI and SLMC as reproduced in the Padeniya Report, SAITM had been called at that time in its original name, namely, South Asian Institute of Technology and Management. Thus, its transformation into South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine would have taken place much later as a marketing device.”

SAITM initially has been a BOI-approved private venture in 2008 to conduct training (and not degrees) in management, nursing, languages, vocational studies, health science and technology. It has been the Ministry of Higher Education and the UGC which have given SAITM, the degree awarding status (August 2011). By that time SAITM had already started recruiting students for medicine. It is important to note that this was Rajapaksa time, while some key decision makers are with the present Government.

However, the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC) has clearly written to SAITM in 2009, among other matters, that it cannot “recognise any degree being awarded by an institution not set up under the Higher Education Act”. This cannot be just a technical matter, which even the UGC has overlooked. The present controversy is much on the substance, for instance, whether the SAITM students have sufficient clinical experience to qualify for national and international standards, whatever the facilities they have in superior to even some of the State-run medical facilities.

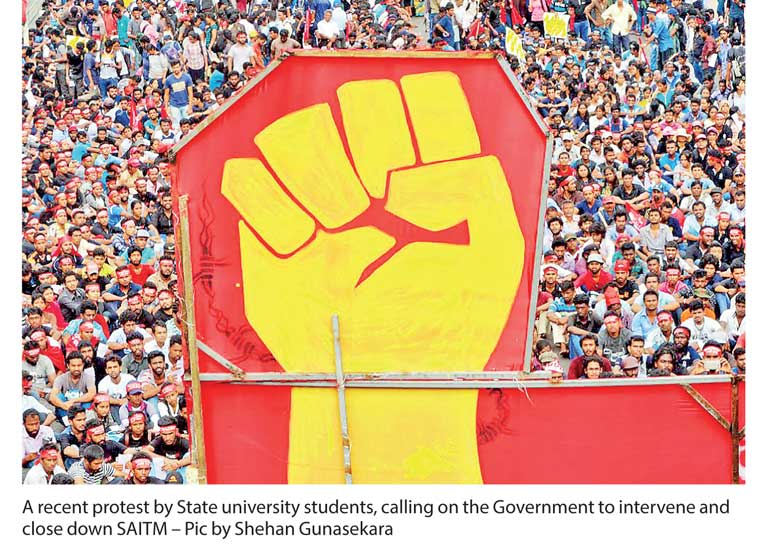

On the part of the university student unions and other trade unions in the country, they question the recruitment procedure of SAITM, based on the capacity to pay high fees, leaving out many more qualified students out of the possibility of entering the lucrative medical profession. If you have, for instance, two Cs (with one S) in bio-sciences, you can enter as a medical student at SAITM but not to a State university, because of the higher Z-score required. Here is a strong equity problem. Even then, enrolment of SAITM students for a batch is not more than 30, because of the financial factor. This cannot even be considered ‘freedom of education’ by any means, they argue. However, the protests should not be at all against the SAITM students or even SAITM, but against the prevailing injustice.

Medical graduates are the only graduates who are assured of secure employment in the country. Therefore, all those who are qualified should have the opportunity to enter medical education, whatever the determined minimum qualification. There are more and more good doctors needed in the country. They also have the opportunity to go abroad and earn a good living, whether they contribute back to the country or not. On the other hand, there is nothing wrong, under the circumstances, in having fees for medical students either on the direct payment basis (like at SAITM) or on an interest free loan basis like HELP (Higher Education Loan Program) in Australia in the long run. However, this is not an issue that should be settled now. Much more discussions are necessary.

Somapala Gunadheera has admirably expressed his strong concerns about the debilitating effects that are created due to the unresolved status of the SAITM issue including the staged and threatened strikes (‘Settle SAITM issue to avoid a breakdown,’ The Island, 4 May). He has quoted very clearly the ‘unfavourable outcomes’ and ‘ill-effects’ that the Association of Medical Specialists has pointed out which are already visible in the national health system, as a result of the current crisis.

Towards resolving the ongoing controversies, Gunadheera has further summarised the proposals of the Medical Dean’s Association (MDA), the Association of Medical Specialists (AMS) and – partial though – SAITM’s responses to the above proposals, also noting GMOA’s positive reactions to many of the proposals of the MDA. If these are genuine and correct, a solution cannot be far away.

In the meanwhile, the Government has come up with a ‘Six Point Proposal’ to the situation. From the look of them, they fall far short of the ‘demands,’ the other expert proposals or the key issues of the controversy. As reported in The Island lead article (‘SAITM Crisis Takes New Turn,’ 4 May), they are as follows:

(1) Listing of SAITM in the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE).

(2) New administration under a board of directors.

(3) SAITM students who have already passed the final MBBS examination would be given a further period of clinical training in Surgery, Medicine, Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Psychiatry and Paediatrics, one month each in duration, at the Homagama and Avissawella hospitals.

(4) Subsequent to this training, candidates would undergo a mandatory examination conducted for granting provisional registration under the joint supervision of the SLMC and the University Grant Commission.

(5) The Ministry of Health would gazette the minimum standards for medical education in Sri Lanka submitted by the SLMC with the approval of AG.

(6) The Ministry would initiate the proceedings to bring the Neville Fernando Teaching Hospital under the Ministry of Health and continue to run it as a teaching hospital.

Frankly speaking, the first and the key proposal of “Listing of SAITM in the Colombo Stock Exchange” is like ‘Koheda Yanne, Malle Pol’ (Where are you going? Coconuts in the basket!). The second is the same. The third and also the fourth are necessary, whether the further clinical training is given at Homagama or Avissawella. The fifth is a long-standing requirement, not fulfilled until now, without direct relevance to the present SAITM controversy. The sixth proposal appears to divert the issue and the whole effort of proposals appear to be to make mere managerial changes. If the Ministry of Health can take over the Neville Fernando Teaching Hospital, why cannot the Ministry of Higher Education and the UGC take over the SAITM Faculty of Medicine, one can ask?

One can even suspect or argue these proposals to have ulterior motives and/or self-interests. Who would be the new managers? Who can assure the new managers are going to be better than the old? Who is eying for the shares and the new management? Instead of resolving the existing problems, the proposals appear to create new problems and new controversies.

To find a possible solution, the key question identified by Ruwan Weerasinghe – ‘Can the Medical Education be provided by the Private Sector? – needs to be answered. The answer seems to be (as far as I am concerned), ‘Not at present.’ The efforts by SAITM may be considered admirable. But the efforts have failed. The patient is dead. The two main proposals by the Medical Dean’s Association are:

(1) Stop admissions to SAITM with immediate effect.

(2) Stop SAITM from granting an MBBS degree forthwith.

Whatever the arguments/apologies that SAITM has offered to protect its credibility, what I have found strange is the non-listing of its academic staff in the faculty’s website. There is no portal for Staff! To be fair, Rajarata University medical faculty also does not have a portal for staff, although names and pictures are given here and there.

This is not the first effort to conduct medical education by the private sector. The first effort of the North Colombo Medical College (NCMC), started in 1981, also failed. The opposition to that effort also was tainted with political/ideological reasons as is the case today. However, it was closed and became taken over by the University of Kelaniya under President Ranasinghe Premadasa administration in 1989 for pragmatic reasons. Because it was a failure. The same thing can be said about the medical faculty of SAITM, while the present effort can be considered more professional. The medical faculty should not be just scrapped, however, as the medical education should be expanded in the country.

The present SAITM consist of five faculties: (1) Medicine (2) Engineering (3) ICT and Media (4) Management and Finance and (5) Allied Health and Behavioral Sciences. There is no need to take over all faculties, but medicine. There can be similar concerns about engineering, but not at present.

The Faculty of Medicine can be affiliated to the University of Moratuwa, which is the only prominent university without a medical faculty, or any other. SAITM even can continue in that acronym, but going back to its original name: South Asian Institute of Technology and Management. Necessary other measures are already there in various proposals (MDA, AMS, SLMC, GMOA etc.), including the government proposal. A committee representing all stakeholders can be appointed under the UGC to sort out all other datils. There is a precedent, on how such a transition can be made in the experience of the North Colombo Medical College.

If the Ministry of Health can take over the Neville Fernando Teaching Hospital, why can’t the Ministry of Higher Education and the UGC take over the SAITM Faculty of Medicine?