Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 23 April 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

With these ongoing natural and manmade environmental changes, we cannot take all our dams for granted

Today, dams are indispensable structures for human prosperity and play a considerable role in the world economy and Sri Lanka without exception. There are more than 59,000 large dams all over the world according to registered data of the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD).

Today, dams are indispensable structures for human prosperity and play a considerable role in the world economy and Sri Lanka without exception. There are more than 59,000 large dams all over the world according to registered data of the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD).

A dam is categorised as a large dam if the height of a dam is greater than 15 m. A dam of height 5-15 m is also considered a large dam if its storage capacity is more than 3 MCM. Accordingly, Sri Lanka has got around 94 large dams, 270 medium dams, and over 10,000 small dams. According to the ICOLD, China has the highest number of large dams numbering 23,841 while the USA and India rank second and third respectively. When dam type is concerned 65% of large dams are earthen dams and the main purpose of 47% of dams is to provide irrigation water.

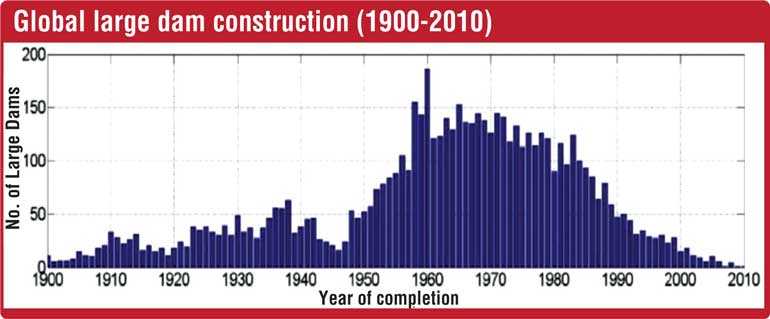

Similar to many other man-made structures, dams too have a finite lifetime. In technical terms, it is defined as the design lifetime, which is generally, 100 years. However, many dams may exist longer than the design lifetime while some may fail even a short time after the commissioning owing to design or construction faults and natural calamities as well. Many large dams in the world have been built during 1950-90 being an era of intensive dam construction.

In Sri Lanka too, except Kaluganga and Moragahakanda dams, many of the other Mahaweli multi-purpose reservoirs were commissioned in the 1980s under the accelerated Mahaweli development program. But the question is if the lifespan of a dam is 100 years how many of those dams will be left for us by the year 2100. The awful, though speculative, answer is nearly zero. Nevertheless, many dams will exist beyond their projected lifetime if we take care of them properly as discussed in detail below.

Factors affecting the lifetime

The basic determinant factors of the lifetime of a dam are either the structural failure of the dam or siltation that make it no more usable due to loss in active water holding capacity. However, dam failures are rare though the failure of which could be disastrous. There is a growing concern about the seismic safety of dams with the recent earth tremors that occurred around Victoria dam. However, according to the reports, the main cause of dam failure in the world is foundation problems while inadequate spillway capacity being the next. Although earthquakes cause huge damages to the manmade infrastructure, only less than 1 percent of dams have failed as consequences of earthquakes.

In the context of ongoing climate change, there will be more intensive rains that generate unprecedented inflows to reservoirs. Unless the reservoirs’ spillway capacities are adequate or augmented to cater to the future requirements of changed rainfall characteristics, there will be high chances of failure due to overtopping.

When a dam is no more usable due to either safety reasons or loss of capacity after excessive siltation it would have to be decommissioned. Sometimes the purpose of such decommissioning may be restoring the ecosystem or preventing harmful effects. In Sri Lanka, many small dams at the village level have been abandoned due to breaching or natural effects like insufficient rainfall or for reasons unknown. However, we are yet to experience a purposeful decommissioning of a dam. In contrast, nearly 800 dams have been removed in the US in the last 100 years ratifying the case in point.

The plight of major dams in Sri Lanka

Today, modern technology helps us to monitor the health of the dams properly. Some of the recent projects implemented by the Government intended to assure the safety of the major dams by carrying out necessary improvements. Hence, it is unlikely that we will witness a dam failure disaster in our country like that of the Kantale dam in 1986, which is considered the biggest dam failure event in the recent past. Hence, it is not the safety of the dams that is critical now but the sustainability of our dams.

Many recently built major dams of the country that hold big water storage lie in the mountainous areas in the upcountry. Many of them will reach the end of the designed lifetime by the end of this century when the excessive soil erosion led siltation is considered. As a rule of thumb, the reduction in the active capacity of a reservoir per annum is 1%. However, the rate will further escalate if the catchment areas of such tanks are prone to deforestation, which would result in more and more soil erosion.

Eventually, the water holding capacities of the reservoirs will irrevocably decrease. For instance, the Rantambe dam has lost its capacity by 45% due to siltation during 34-year lifetime according to Prof. S.B. Weerakoon. The majority of these reservoirs are serving agricultural land by providing water for irrigation while some are multipurpose contributing to hydropower generation. The installed hydropower generation capacity of these dams is about 33% of the total power generation capacity of the country while the actual generation remains around 23%. The reduction in generation potential is mainly due to variation in rainfall and that would be further worsened as an impact of climate change.

In the meantime, many of our dams in the low country may experience fewer siltation issues. A recent bathymetric survey carried out by the Climate Resilience Improvement Project of the Ministry of Irrigation has revealed that capacity loss in the Nachchaduwa dam due to siltation is almost zero. Presumably, the reasons for less siltation are the flatter watershed consisting of ample forest cover with less soil erosion potential and the cascade minor tanks system in the watershed area that retains the silt transported with the rainfall-runoff. Hence, we can assume that many of our low country dams are still maintaining their original capacities if similar conditions prevail as those of Nachchaduwa.

Present challenges

With these ongoing natural and manmade environmental changes, we cannot take all our dams for granted. If the total storage capacity of our dams is reduced, the potential for providing irrigation water, drinking water and generating hydropower will also go down. So, we have to pay attention to this imminent issues and challenges sooner than later. We will have to switch to alternatives ways of managing our water resources in order to sustain our irrigated agriculture. Further, a considerable portion of hydropower will have to be replaced with alternative sources preferably renewable energy.

There are only a few lucrative options left for us to manage the impending crisis; the option of reservoir desilting is not discussed here being a reactive measure, probably the last resort, which goes against the objective of this write-up.

Firstly, we have to protect the existing dams not only by doing structural renovations but also by conserving the whole watershed areas of them against deforestation and activities that increase soil erosion to minimise the capacity loss due to siltation. Secondly, we have to increase the water use efficiencies of our irrigated agriculture to the best possible level in line with the concept of more crop per drop. Thirdly, we have to switch to other renewable energy sources, which could compensate for the decreasing hydropower capacity in the future amidst the growing demand. The success of all these actions depends on the genuine understanding of the challenges ahead and prompt actions of all the stakeholders.

(Eng. Thushara Dissanayake is a Chartered Engineer specialising in water resources engineering with over 20 years of experience.)