Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 8 January 2019 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Maithripala Sirisena. Mahinda Rajapaksa. Ranil Wickremesinghe. We’ve had different leaders with the same unhappy results for decades. At the core of this country’s political gridlock and dysfunction is a failed leadership culture and not a few men jockeying for power.

Our existing model of representative leadership and behavioural conduct urgently needs fixing, as does fast tracking the empowerment of a new generation of leaders in the UNP. And yet we often forget that leadership is also a two-part equation. Followers have their own identity, just as leaders have theirs. In fact, Michael Maccoby, a leadership expert who has advised, taught, and studied the leaders of companies and governments in 36 countries, says: “Followers are as powerfully driven to follow as leaders are to lead.”

To better understand the strength of the bond between leader and led – or the extent to which followers believe they should follow – Geert Hofstede, a social psychologist at IBM, collected and analysed data from over 88,000 employees in 72 countries to ascertain how national culture influenced people’s behaviours in organisations, institutions, and families, as well as their self-concept.

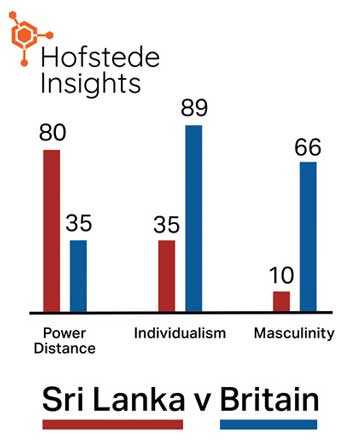

Hofstede developed the now familiar construct of “power distance”, which he defined as “the extent to which the less powerful members of organisations accept and expect [my emphasis] that power is distributed unequally”. In Sri Lanka – which measures 80 on the Hofstede Comparative Power Distance Index and is therefore categorised as a high power distance culture – “people accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and that needs no further justification.”

At work, for example, organisations are characterised by tall pyramids with leaders who are directive in style, instructing their followers on what to do and how to do it, as well as implicitly or explicitly discouraging and/or punishing any questioning of their authority.

But followers also avoid making decisions because they expect to be told what to do; they are obedient, deferential and do not freely express their thoughts, opinions, emotions, doubts or disagreements in the presence of superiors/seniors; when they do, they choose to answer vaguely or indirectly rather than reply with a direct “no”.

“Hierarchy is seen as reflecting inherent inequalities, centralisation is popular, and the ideal boss is a benevolent autocrat,” says Hofstede.

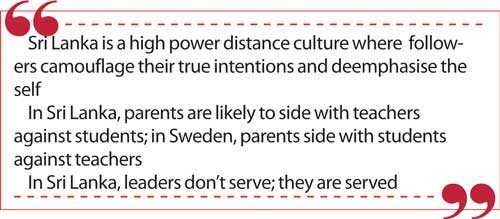

In Sri Lanka, a high Power Distance score of 80 indicates a culture where hierarchy reflects inherent inequalities, centralisation is popular, and the ideal boss is a benevolent autocrat. A low score of 35 for Individualism implies a strong collectivist stance that emphasises the “we” and “our” over the “I” and “my”; the culture values followers who fit in and conform by camouflaging their true intentions and deemphasising the self. A low score of 10 for Masculinity signals a lack of assertiveness; status is preserved through social relationships and by avoiding shame and loss of face, rather than material success and individual achievements. The traits best represent mainstream Sinhalese employees and voters.

Research by Meina Liu, a professor of communications at Georgetown University, also helps to explain indirect communication styles in high power distance cultures: she describes, for example, how leaders/superiors/seniors take precedence in seating, eating, walking and speaking, while their followers wait and proceed after them.

Sri Lankan historian Dr/ Michael Roberts has also explored the role of language in reinforcing this leader-follower/superior-subordinate relationship: followers/common people “go” (yanava) whereas leaders (in his example, kings and monks) “proceed” (vadinava), followers/common people “eat” (kanava) while their leaders “dine” (valandadanava).

Of course, examples of top-down leadership exist in every country, but what makes power distance especially relevant to hierarchical cultures like Sri Lanka (as well as Malaysia (100), the Philippines (94), China and Bangladesh (80), Indonesia (78), India (77) and Singapore (74) is the extent to which it is culturally reinforced at all levels of society. (Incidentally, lower power distance cultures – such as the United States (40), United Kingdom and Germany (both 35), Norway and Sweden (both 31), Denmark (18), and Australia (36) and New Zealand (22) – distribute power through decentralised organisations where followers habitually question authority and reject authoritarian leaders).

Let’s take schools. Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD, explains how students in Nigeria (which also measures 80 on the Hofstede Comparative Power Distance Index) are highly deferential to teachers both inside and outside the classroom, and kneel before elders as a mark of respect. In sharp contrast, students from Sweden call their teachers by their first names and are expected to openly contradict them in classes. In Nigeria, Sri Lanka and other high power distance cultures, parents are likely to side with teachers to maintain order and the power hierarchy. In Sweden and other low power distance cultures, on the other hand, parents commonly side with students against teachers.

But we need to work back to the first social group we are introduced to in our preschool years – our family – to better understand how we learn to defer, obey and conform.

When Michael Maccoby interviewed managers in Asia, Europe, and North America, he asked interviewees two questions: “What is your view of a good manager, and what is your view of a good father?” The answers were related, but there was a clear distinction between Western and Asian managers.

Americans and Scandinavians viewed good managers and good fathers as people who supported their followers when needed, but generally encouraged them to be independent. By contrast, Asians (who came from traditional families with authoritarian fathers) wanted a father-manager who taught and protected them. In exchange for this, they gave the leader their complete loyalty and obedience. (Asian managers also considered Western leaders to be bad parents who neglected their children’s needs).

These very first leaders – our parents and their parenting style – play a crucial role in influencing our relationships with the superiors and subordinates we subsequently encounter in our lives.

For example, Diana Baumrind, who first developed the concept of parenting style, provides a four-fold typology: indulgent, authoritarian, authoritative, or uninvolved. She describes authoritarian parents (the prevalent type in Sri Lanka and other high power distance cultures) as “obedience- and status-oriented, [who] expect their orders to be obeyed without explanation”; they integrate their children into the family (and later social) whole through a high degree of behavioural control, including the supervision and reinforcement of rules, disciplinary action against disobedience, and by withholding affection and praise.

For example, Diana Baumrind, who first developed the concept of parenting style, provides a four-fold typology: indulgent, authoritarian, authoritative, or uninvolved. She describes authoritarian parents (the prevalent type in Sri Lanka and other high power distance cultures) as “obedience- and status-oriented, [who] expect their orders to be obeyed without explanation”; they integrate their children into the family (and later social) whole through a high degree of behavioural control, including the supervision and reinforcement of rules, disciplinary action against disobedience, and by withholding affection and praise.

Largely as a result, children with high dependence needs – or a low independence stance – expect to be instructed or directed by their parents and other authority figures such as teachers and principals. Later in life, as they affiliate with surrogate families and father-figures – organisations, institutions, and groups, as well as CEOs and political leaders – they replicate the same parenting style and once again reinforce submission towards leaders/superiors/seniors: of their children/employees towards them, and themselves towards their leaders.

Much of this, I believe, clarifies the disposition of Sri Lanka’s docile employees towards CEOs and submissive voters towards politicians. It tells us why policemen are incapacitated in the presence of politicians, and why parents and students revere teachers and principals. It helps us understand how the executive presidency endures and why mainstream society is so permissive of hierarchy and authoritarianism. It explains why we lack innovative businesses and brands, and why nothing really ever changes.

Hoftstede’s findings are extremely important because they give us a greater understanding of how a society’s level of inequality is endorsed from below as well as above. In high power distance cultures, followers accept as appropriate and beneficial that power is distributed unequally. In Sri Lanka, leaders don’t serve; they are served.

(The writer is a consultant.)