Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 27 February 2023 00:17 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Enhancing the independence of the CBSL is one key essential reform that would facilitate several positive spill-over effects in the economy that would enhance the public welfare

1.0 Central Bank Independence: What is it and why is it important?

1.0 Central Bank Independence: What is it and why is it important?

The term ‘Independence’ refers to the state of being able to make your own decisions, without influence from others. Similar meaning could be attributed to the Central Bank Independence (CBI). It is the state that a central bank operates without undue influence from the government. The need for CBI is often explained through central banks’ unique power of printing money. Governments are elected by the people to serve them for short periods of time. It is not surprising that governments act to please the public by adopting populist policies to stay in power and to be re-elected. Such expansionary polices yield short term favourable outcomes and require more money without passing much of the tax burden to individuals and businesses.

Since governments do not have the ability to print money on their own, they could expect central banks to do it. Large scale continuous money printing to finance government budgets and keeping interest rates low for long lead to excessive availability of money in a country (money supply), thus creating the unfavourable consequence of high inflation––even hyperinflation–– and balance of payments crises in most instances. High inflation reduces the purchasing power of people, erases savings and wealth, favours borrowers at the cost of savers, and discourages production. Inflation is often described as ‘inflation tax’ that is regressive in nature.

It disproportionately affects the poor, thereby widening the income and wealth gap between the rich and the poor. Thus, central banks around the world are mandated to preserve the value of money by keeping inflation low, thereby supporting economic stability. Independent central banks stay away from undue political interferences in achieving their mandated price stability objectives.

The Great Inflation episode experienced worldwide during the 1970s was an eye opener for the world to recognise the importance of monetary stability and the need for establishing independent central banks. The transformation towards CBI since then helped moderate inflation trends to a great extent, avoid macroeconomic calamities, and reduce the frequency of financial crises. Empirical evidences have shown the macroeconomic stabilisation effect of CBI and proved that CBI is linked to lower inflation, lower inflation variation, increased credibility of the monetary policy, and lower uncertainty among economic agents (Garriga, 2016). Further, the role of CBI in maintaining lower budget deficit and debt sustainability has also been empirically stressed.

The literature on CBI distinguishes between the Goal Independence and Instrument Independence. Goal independence is the autonomy for a central bank to set its own goal (monetary policy), whereas the instrument independence is associated with the autonomy in the choice of best instruments to achieve the prescribed target. While there is consensus on the need for instrument independence of central banks, there are opposing views on the degree of goal independence that central banks should have. Recent studies and expert opinions stress that goal independence makes central banks too powerful, thus they should be dependent on the goal determined by the political process (Mishkin, 2000).

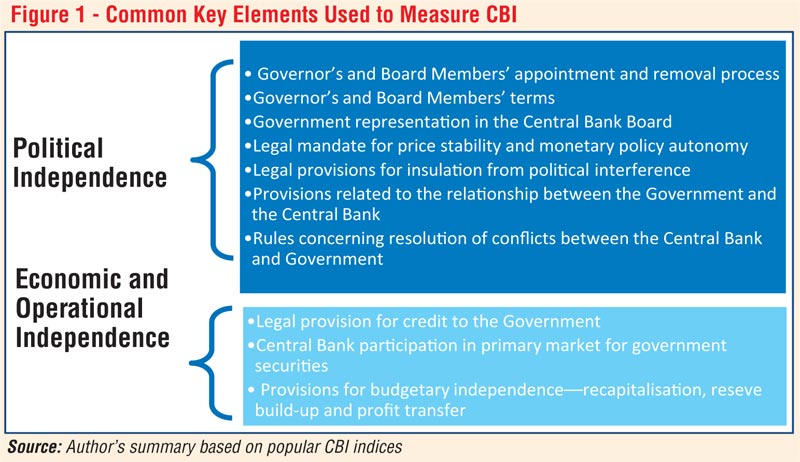

CBI is measured in relation to several aspects, of which legal powers from political interference is the key starting point. Financial and operational independence complement the legally established powers. Though central bank legislations in many countries provides legal independence (de jure independence), this does not automatically translate into actual operational independence (de facto independence). Several indices have been developed from time to time using many factors to measure and compare CBI across several countries. Elements that are commonly used in popular indices to gauge the level of operational autonomy of central banks are summarised in Figure 1, classified under two main areas.

2.0 Arguments against making central banks independent and remedies

Despite the broad consensus established on the importance and benefits of enhancing CBI, there are counter arguments and oppositions among political leaders, academics, and the public in allowing central banks to operate independently. These opposing views make this subject lively and debatable. A recent study by the European Central Bank confirmed that actual independence of central banks of some of the largest economies has weakened over the years, even though the de jure independence did not deteriorate (Dall’Orto Mas et. al., 2020).

Central banks have been increasingly challenged in the recent years by the populist politicians, market lobbyists and the public. The public statements against Governors and central banks by the political leaders in major economies, (USA and India) and the removal of Governors due to non-adherence to governments’ instructions in some countries (Turkey, Argentina, Zambia) in recent years have challenged CBI.

Moreover, the world experienced some instances where Governors and Board Members of the central banks were biased towards the ruling governments, regardless of the high level of legal autonomy given to their central banks. Opponents of CBI argue that greater independence will lead to monetary management moving from the control of governments to technocrats at central banks, thus weakening the public confidence. They stress that CBI is undemocratic as it gives excessive powers to central bank boards and staff, who are generally treated as elite by the public.

The main remedy for criticism of CBI is enhancing the accountability and transparency of central banks, which is instrumental for improving public confidence and public support. Independence and accountability are two sides of a coin and the coin becomes valueless if a side is empty. Central banks with excessive power and autonomy from the governments should not act in a vacuum but should be held responsible to the legislature and the public for their actions. Paul Tucker in his book Unelected Power explained that unelected central bankers need to be constrained by legislation and governed by certain principles to remain legitimate; including accountability, effective communications, and self-restraint. Several legislative provisions are inbuilt in many central banks’ acts for enhanced accountability. Meanwhile, central banks are increasingly becoming transparent through their communications not only to adhere to legally bound accountability but also to gain public confidence and to establish credibility.

Modern central banks currently adopt certain communication mechanisms, such as publishing inflation report and other technical reports to explain policy rationale, public release of monetary policy board minutes, holding press conferences and public events, attending hearings of the parliament, and publishing open letters to the public on important economic and policy matters, in order to exhibit their openness and accountability.

3.0 Where does Sri Lanka stand?

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) is currently governed by the Monetary Law Act (MLA) of 1949. The rationale underpinning some of the provisions of the MLA was very much relevant to the country immediately after independence. The growth and development objectives and the essence of close coordination between the CBSL and the Government were spelt out in the MLA and the Exter Report1. Multiple developmental objectives were later refined through legislative amendments justified by the practical difficulties in compromising one objective over the other at times of conflicting interests. Some of the existing arrangements in the current legislation have made it possible for direct government influences on the monetary policy formulation and other operations of the CBSL.

The Exter Report has recognised the possible consequences of such influences on the Monetary Board at the time of the enactment of the MLA as follows:

“The effectiveness of this co-operation and co-ordination between the (Monetary) Board and the Government will depend more upon the men occupying the key positions at particular times than upon any legal formula, no matter how carefully or elaborately it might be worked out. A relationship as complex and sometimes as delicate, as this one is certain to be, cannot be established full-blown by a piece of legislation. It must be the result, as in other countries, of years of experience and the slow growth of political convention “.

In the history of the CBSL spanning over 70 years, there is no clear evidence that such political convention has emerged in Sri Lanka. The CBSL is currently weak in many elements of CBI that are listed in Figure 1. Many studies that attempted to measure and compare CBI across many countries have allocated a score between 0.5 and 0.6 to the CBSL, compared to the complete score of 1.0 allocated for an independent central bank. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand and The Bank of England are generally commended as modern, independent central banks. The presence of the Secretary to the Treasury at the Monetary Board, even though it helped to create close coordination between the monetary policy and the government policies, hinders the autonomy of monetary policy formulation.

The Exter Report emphasised the presence of the ‘Permanent Secretary’ at the Monetary Board as the primary mechanism to establish continuous and constructive cooperation between the CBSL and the Government. However, with the abolition of the post of permanent secretary since 1972 in Sri Lanka, the presence of the Secretary to the Treasury, who is appointed by the Head of State and represents the views of the present Minister of Finance, has weakened the autonomy of the CBSL (Wijewardena, 2018). The removal process of the Board Members, including the Governor, is relatively weaker at the CBSL than that of independent central banks.

The existing provisions of the MLA allow primary market purchases of Treasury bills by the CBSL. This provision has been frequently used by successive governments to finance the government budget deficit, debt servicing and other purposes. Such monetary financing had notable implications on the country’s monetary and macroeconomic stability. Moreover, the provision of provisional advance to the Government at the beginning of the financial year has created a permanent funding avenue for the Government. These legislative arrangements and excessive use of these provisions have weakened the economic and operational independence of the CBSL, and have contributed to the fading credibility and public confidence on the CBSL. The lack of instrument autonomy has manifested through large scale monetary financing and financial repressions in Sri Lanka in the recent times, having implications on the severity of the current crisis (Coomaraswamy, 2022).

4.0 The way forward for a more independent and accountable central bank in Sri Lanka

The process of strengthening the autonomy of the CBSL should begin with legislative amendments. Central banking has evolved tremendously since the 1950s and thus the MLA, which is over seven decades old, lacks some arrangements needed for a central bank operating in the 21st century. Thus, the need for a new act to govern the CBSL was recognised as the key step to improving the CBSL’s governance and independence. Accordingly, initial Cabinet approval for the proposed set of amendments to the MLA was granted in April 2018 and a comprehensive draft of amendments to the MLA was prepared and the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Bill (CBSL Bill) was gazetted in November 2019 to provide for the establishment of the CBSL and to repeal of the MLA.

Unfortunately, the CBSL Bill could not be passed in the Parliament in 2019 due to subsequent changes in the political arena. The discussion on the need to strengthen the CBSL’s independence has resurfaced in 2022 with the prevailing unprecedented economic, social, and political challenges in the country. Obtaining approval for IMF -Extended Fund Facility (EFF) will reiterate the enactment of the CBSL Act, which was also a pending structural benchmark under the IMF- EFF arrangement in 2016-2019.

Moreover, the Government’s macroeconomic stabilisation programme recognises the essence of strengthening key institutions. Accordingly, the CBSL Bill of 2019 with some further amendments has been finally approved by the Cabinet in February 2023 and the new CBSL Bill has now been gazetted. The CBSL Act is expected to be enacted in early 2023.

The CBSL Bill provides the necessary legal framework to adopt Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) as the monetary policy regime of the CBSL. The key highlights of the salient features covered in the CBSL Bill are listed in Table 1. By design, the FIT framework encompasses key elements of CBI: accountability and transparency. It is built on the strong foundation of price stability mandate with more accountability to the public through the central bank’s commitment to maintain inflation at the targeted level and transparently communicate the medium term forecast and policy rationale.

Further, FIT provides a benchmark in the form of a nominal anchor (inflation), based on which the performance of the CBSL can be measured. Moreover, a Monetary Policy Framework Agreement will be signed by the Minister of Finance and the CBSL to set out the inflation target to be achieved by the CBSL. This arrangement would engage the Government also in the process of goal setting, while enabling instrument independence of the CBSL in achieving the target. Further, embedding FIT framework within the CBSL Bill strengthens the power of the CBSL to carry on its policy formulation without much external influence, while also improving its credibility and public confidence.

The removal of government representation in monetary policy formulation and the prohibition of monetary financing of budget deficits would enhance instrument independence. Also, the CBSL Bill clearly defines the relationship between the Government and the CBSL, ironing out misinterpretation and misuse of the ambiguity about the role of the CBSL in certain areas related to the Government.

The CBSL commenced adopting the FIT framework in 2020, even in the absence of some key pre-requisites, mainly the lack of de jure independence of the CBSL, the freedom from fiscal dominance and the Government involvement in inflation target setting through the framework agreement. Insulating monetary policy formulation from political pressures and ensuring more economic, financial, and operational independence would help restore the credibility of the CBSL in the eyes of internal and external stakeholders.

Sri Lanka should take the current economic crisis as the golden opportunity to restart the country on a stable path supported by essential structural reforms. Enhancing the independence of the CBSL is one key essential reform that would facilitate several positive spill-over effects in the economy that would enhance the public welfare. The CBSL must also seize this opportunity to restore public confidence by being more accountable to serve its principal, the public. It is appropriate to conclude this note with the following quote from Sir Edward George, former Governor of the Bank of England.4

“Whatever the formal arrangements applying to the central bank, the political and public confidence on which our (central banks’) position depends is something that we (central banks) need to continuously earn through personal and professional integrity, objectivity and competence.”

Footnotes:

1The Exter Report is the report on the establishment of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (Ceylon) that provides the rationale and the legal framework for this establishment by the technical expert John Exter, who became the first Governor of the CBSL.

2A provision is included to allow for temporary provisional advances subject to stringent terms and conditions.

3However, a transitory provision has been included to allow for primary market purchases within six months from the appointed date under stipulated conditions to allow for some flexibility during the transition.

4Speech at the SEANZA Governors’ Symposium in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on 26 August 2000.

References:

1. Coomaraswamy, I., (2022), ‘Central Bank Independence: Does it matter for the Country’s Economic Prosperity?’, 72nd Anniversary Oration, Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

2. Dall’Orto Mas, R., Vonessen, B., Fehlker, C., & Arnold, K., (2020), ‘The Case for Central Bank Independence: A Review of Key Issues in the International Debate’, Occasional Paper Series, No. 248, European Central Bank.

3. Garriga, Ana Carolina, (2016), ‘Central Bank Independence in the World: A New Data Set’, International Interactions, Vol. 42 (5): 849-868.

4. Mishkin, F. S., (2000), ‘What Should Central Banks Do?’, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, November/December 2000, pp. 1-14.

5. Wijewardena, W. A., (2018), ‘A Revisit to Central Bank Independence: How to Resolve the Emerging Issues?’, 68th Anniversary Oration, Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

(The writer is an Additional Director of Economic Research of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The views expressed in this paper are those of writer’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)