Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Thursday, 28 September 2017 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Agricultural value chains are complex. A well-functioning value chain means there are enough incentives for producers and sellers to engage. Agricultural value chains expand with time.

Agricultural value chains are complex. A well-functioning value chain means there are enough incentives for producers and sellers to engage. Agricultural value chains expand with time.

A value chain that existed well over a decade will have many stakeholders involved. As the complexity, the number and the scale of stakeholders increases it will not be easy to diversify the value chain, especially when incentives are not clear and large. However things will get easily complicated when the value chain starts aligning with negative externalities.

These negative externalities can be either environment, social, economic or even health. More negative externalities mean more pressure to diversify. However, important questions in such a situation are (1) Is the value chain flexible enough to diversify, (2) Are there enough alternatives to lean on and (3) Are there correct and enough incentives to diversify. Positive answers to these questions mean diversification will not be a painful process for both the producer and seller.

Plenty of research has been done on why tobacco is bad for human health. It also creates negative externalities through secondary smoking and air pollution. Furthermore, research in some countries argues the negative environmental externalities generated by tobacco cultivations. Hence it is natural for policy makers to start a discussion around limiting the use of tobacco.

Agricultural produce, in this case tobacco leaves, will have a demand from cigarette companies which is being catered by the farmers who grow them. Consumption of cigarettes drives the demand for cultivation. Increased consumption calls for increased manufacturing, which results in a higher demand for tobacco cultivations.

If the cigarette consumption (we can include beetle chewing, beedi and cigar as well to this discussion) is to be limited, we can either reduce demand for the product or we could limit the production (supply). Limiting production means limiting the supply of raw materials, that means cutting down the tobacco cultivation. Cutting down tobacco cultivation is directly linked to farmer livelihoods.

Therefore in a nutshell, a policy can either affect the consumer by forcing to reduce the demand (or it might be saving the consumer from lung cancer) or it can affect the farmers by limiting the production and supply of raw materials. Therefore important questions are: (1) who should be our target audience in forming the policy and (2) what option/actions would hurt them less?

This article is not arguing against the tax increases in cigarettes. It is not discounting any of the medical research done on negative effects of tobacco chewing and smoking. The only interests in this article are the farmers in the tobacco value chain, looking purely from an agro-socio-economic lens. Hence the central question this article tries to explore is the “possible socio-economic impacts of proposed tobacco growing ban and the way forward”.

This article shares insights from an independent research work by a group of researchers. Research study is based on qualitative as well as quantitative methods. Qualitative component is carried out with Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and the quantitative component is carried out with a household survey. Focus areas of the study are: Galewela, Pollonnaruwa, Mahiyanganaya, Buttala and Kalpitiya.

This write-up is based on the qualitative component only. Therefore, the details presented are descriptive and less focused on the numbers. This write-up represents the analysis by the full independent research team.

Some key facts on the tobacco value chain

Tobacco is grown mainly for cigarette manufacturing. However tobacco is also grown for chewing with beetle leaves and for manufacturing beedi and cigars. Two types of tobacco are being used with beetle leaves: Sinhala Dunkola and Rata Dunkola. Rata Dunkola is also called Pani Dunkola where the leaves are treated with a sugar pulp extracted using sugarcane.

The majority of tobacco that is chewed with beetle leaves comes from Jaffna, which is the Pani Dunkola. As expressed by farmers who participated in the research, Pani Dunkola is favoured due to its specific taste. Kalpitiya is famous for producing Sinhala Dunkola. Beedi producers buy raw materials for their production mostly from Colombo.

Apart from Colombo, producers buy raw materials from Warakapola, Thanamalwila, Barandana and Hambantota. Tendu leaves in which they are wrapped are imported, and there is a Cess charged on this. Sinhala Dunkola is the main ingredient that goes in to making beedi.

Ceylon Tobacco Company (CTC) handles the tobacco value chain that focuses on manufacturing cigarettes. The Company works with a large farmer network, which includes barn owners as well. CTC is interested in two types of tobacco, Flue Cured Virginia (FCV) and Air Cured (AC).

Making tobacco under FCV conditions involve a tobacco barn, which operates with a heat source and mature tobacco leaves are cured inside. AC methodology involves curing mature tobacco leaves under shady conditions with natural air circulation. The majority of tobacco leaves come to CTC under FCV conditions.

Tobacco produced under FCV conditions comes from areas such as Galewela, Pollonaruwa, Mahiyanganaya, Ududumbara, Theldeniya, Badulla and Buththala. Areas such as Monaragala, Buththala and Wellawaya are famous for tobacco produced under AC conditions. Tobacco cultivation of these areas have existed for more than three generations.

Farmers who cultivate tobacco with CTC bear cigarette tobacco production permits issued by  Department of Agriculture (DOA). CTC supplies fertiliser, plants and other necessary chemicals to these farmers on credit to be recovered at the end of the cropping season.

Department of Agriculture (DOA). CTC supplies fertiliser, plants and other necessary chemicals to these farmers on credit to be recovered at the end of the cropping season.

Tobacco production simply divides into two steps as green leaf and cured leaf production. Harvested raw leaves from the tobacco fields are sold to the farmers who have license to operate tobacco curing barns (barn owners) in green form at a guaranteed price. Barn owners add value to the raw tobacco leaf during the curing process, which they carry out inside barns with a series of operations. Barn owners sell the cured tobacco leaf to CTC at the end of the curing process.

A considerable number of farmers segregate green leaf and cured leaf depending on resource availability, while other farmers amalgamate both operations and run the full value addition process. Mahiyanganaya, Ududumbara, Theldeniya, Badulla and Buththala farmers run green leaf and cured leaf production together while Galewela and Polonnaruwa farmers run separate green leaf and cured leaf production processes due to inherent conditions prevailing in cultivation areas.

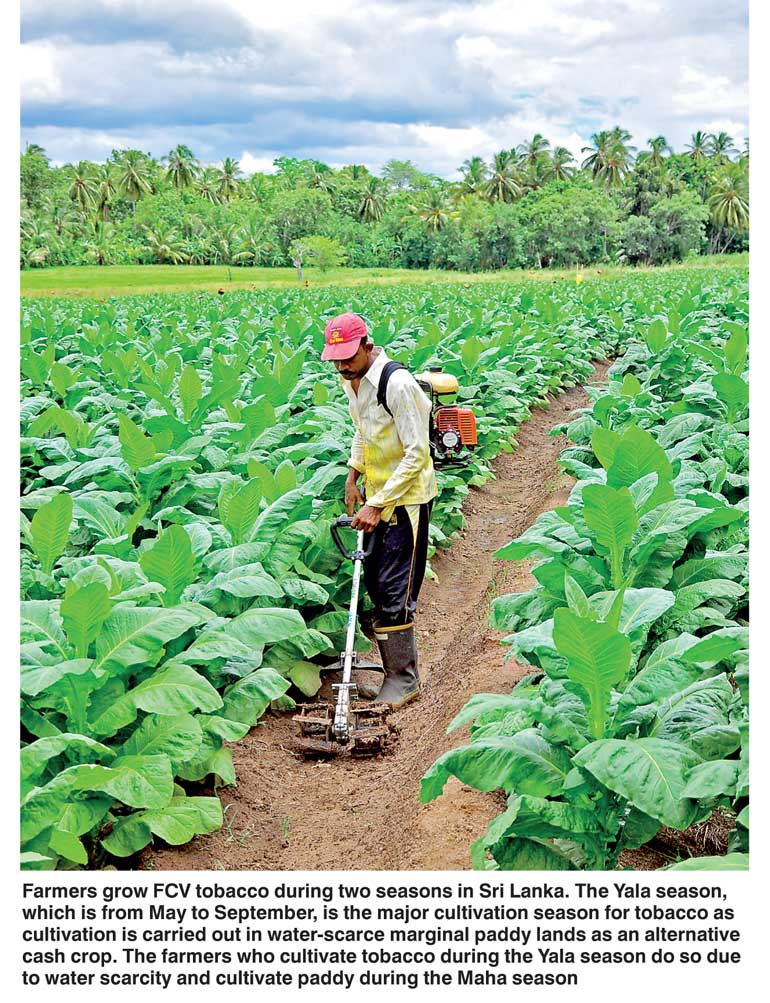

Farmers grow FCV tobacco during two seasons in Sri Lanka. The Yala season, which is from May to September, is the major cultivation season for tobacco as cultivation is carried out in water-scarce marginal paddy lands as an alternative cash crop. The farmers who cultivate tobacco during the Yala season do so due to water scarcity and cultivate paddy during the Maha season. Galewela, Polonnaruwa, and Mahiyanganaya are the major Yala cultivation areas. Maha season which is from November to April is a minor cultivation season for tobacco.

Rain-fed highlands are used to cultivate tobacco during the Maha season. Ududumbara, Theldeniya, Badulla and Buththala are the major areas, which fall under Maha cultivation. In addition to the Maha rain fed crop the farmers in Maha cultivation areas also grow a Yala crop if there is a water shortage during the Yala season.

Why tobacco?

As mentioned earlier, descriptive details from this point onwards are based on Galewela, Pollonnaruwa, Mahiyanganaya, Buttala and Kalpitiya areas. Farmers are exposed to tobacco value chain at different points of time. There are farmers in the Kalpitiya area that engage in tobacco cultivation as third generation farmers, hence their family has been in the value chain for more than 30 years.

At the same time there are farmers who have been introduced to the tobacco value chain very recently. Farmers got in to the tobacco value chain because of the economic benefits it offers. Tobacco yields a higher per acre income compared to any other crop that these farmers know of. Their income has been consistent all this time. Therefore, compared to farmers in other value chains they have been able to earn higher profits from tobacco.

All farmers agreed that tobacco is not an easy crop to cultivate; it is labour intensive, needs fertiliser, timely chemical application, proper pest and disease control etc. However, if grown successfully, it attracts higher profits. As I mentioned earlier, tobacco grown in the Kalpitiya area are taken for chewing with beetle leaves and making beedi and cigars. Therefore, some of these farmers do not have a definite buyer or they do not work under an out-grower contract system.

There is a market discovery cost for these farmers, but the volume and the unit price gave them revenue that easily outweighs the market discovery cost. On top of that most of the tobacco farmers from the Kalpitiya area work with a middleman who tends to absorb a high margin on price. Yet tobacco cultivation is profitable for them, their demand is increasing every year and price has hardly dropped.

For example, price for tobacco grown for chewing, beedi and cigar manufacturing is not based on weight but based on the leaf. On average a leaf will be sold between a price of Rs. 40-50 per leaf after curing (This is not accounting for the recent drop in the price with the proposed ban).

The situation is different for farmers who work with CTC. While the profitability factor holds the same, farmers who work with CTC had more reason to be in the tobacco value chain. Per acre profit is the main factor that attracted them towards the tobacco value chain. But all farmers said that the out-grower model is the one that made them stay. Therefore, clearly there is something larger here.

Farmers who work with CTC did other crops before they got into the tobacco value chain. They cultivated vegetables such as chili, onions and capsicum. They also cultivated other leguminous crops such as mung bean, soya, thala, and maize. All these crops are input intensive. Seeds/plants are costly and hard to grow under nursery conditions. Initial investments are high in terms of getting planting materials and especially the fertilisers and other pesticides (if needed).

If a plantation is destroyed before the harvest, most farmers do not have crop insurance to cover their losses, and they do not have capital either to start things all over again. Therefore, if such a damage happens, most farmers would go out of cultivation altogether.

Let’s assume they somehow manage to get a good harvest, still they have to invest time and money to sell. Their market discovery cost is so high that most farmers avoid these costs by selling everything at the farm itself for a very low price to the middleman. None of these farmers have a storage capacity and they do not have money to invest on post-harvest technologies and value addition. At the end of the day most farmers end up not making enough money, debt cannot be paid and they are tied in the never ending vicious cycle of poverty.

However, the out-grower model with CTC addressed almost all of these issues for these farmers. They were given a guaranteed price, hence the market discovery cost is zero. They were given plants, fertiliser and any other required chemicals on cost recovery basis (CTC give issue seeds free of charge to all farmers). Cost for these items were deducted when the harvest is sold back to CTC.

Farmers were also given other seeds (mainly leguminous) for free so they can practice intercropping. CTC bought their entire tobacco crop, for example the main quality categories were from category (1) to (6), however CTC committed to buy even quality category (9). Therefore, the losses are minimum and farmers could earn from everything they produce.

CTC arranged a long term phased out recovery system if crops were destroyed due to natural disasters, considering the reliability of farmers. In addition, for farmers who had monetary difficulties in managing cultivation (for example paying labour or paying the land rents), CTC extended their hand by authorising small scale loans. Hence this was a perfect model for a typical Sri Lankan farmer.

Another additional but important aspect that came out of the qualitative discussions was the fact that tobacco is resistant to larger pest attacks such as elephants, monkeys and peacocks. Areas such as Monaragala, Buththala and Wellawaya are famous for elephant attacks in the agriculture sector.

Apparently, as mentioned by the farmers, tobacco seems to be the only cash crop that they can produce without getting destroyed by elephants. Therefore, as perceived by the farmers in the tobacco value chain, out-grower model by CTC seems to be addressing all the typical issues that agriculture farmers have: market discovery cost, investment cost, wastage problem, risk mitigation (if they had to restart cultivation, the investment is taken care of) and large pest management.

Farmers did talk about other incentives that they receive from CTC, for example agriculture equipment. All these elements together are not visible in a typical out-grower model.

Life after tobacco

All the farmers (including barn owners) accounted their achievements in terms of social wellbeing to the cultivation of tobacco. This is not surprising given that the value chain is capable of extracting higher economic rents (profits).

Farmers mentioned that they were able to build new houses, send their children to tuition classes, buy agriculture equipment and even motor bikes and dual purpose vehicles. All these are again not surprising and can be accounted towards the higher profits that this value chain generates.

However, something interesting came up during the discussions with tobacco barn owners and farmers. They mentioned that they were able to obtain bank loans easily, especially without signatures of two government employees and a deed of a fixed asset. The significance here is the trust that financial institutions place on this value chain. Tobacco value chain defended farmers’ financial capability in front of a formal lending institution.

Another interesting aspect of this value chain is the relationship between the farmers and the barn owners. As mentioned earlier, CTC directly deals with the barn owner. Farmers who work with barn owners were loyal to them. Regardless of the barn owner, farmers receive the same price, hence one cannot expect a competition among barn owners to have farmers working under them.

What made them loyal to their barn owners is the additional incentives that they would offer to the farmer. It is true that the barn owners are well off compared to the farmers working under them. However, that financial stability allowed the barn owner to help the farmer in other matters, for example in the case of a wedding or a funeral.

As I mentioned earlier, farmers pointed out that tobacco is input intensive. This value chain is complex. There are many direct as well as indirect stakeholders. For example, barns use paddy husk in curing tobacco leaves. Paddy husk is a by-product of the paddy milling process and is mostly wasted or sold at a cheaper price. However as mentioned by the farmers, tobacco barns have created a competitive market for the paddy husk in the area as well.

Talking to tobacco farmers in the Galewala and Polonnaruwa areas, they noted that labourers come to harvest leaves very early in the morning. It was interesting to note that meals for these workers are prepared by the surrounding households and majority of those households had government employment. Therefore, in a way the tobacco value chain provides economic opportunities for the low and middle income government employed households.

In Kalpitiya, labourers work around 20-30 days in one field and then move to another. On a particular cultivation they would harvest and help in drying the leaves. They stay at a “waadi” house (A temporary shelter with coconut leaves). They work for a wage of Rs. 1,600 per day where three meals and two teas are provided. This is the only occupation they have and they move from land to land throughout the year.

A significant portion of labourers are dependent on this in Kalpitiya. In addition, another set of labourers provide the coconut leaves and “pan paduru” to dry and store tobacco leaves. Therefore, as stressed by the farmers, all these people have a livelihood thanks to the tobacco value chain. Qualitative discussion revealed many such indirect employment and economic opportunities and I am happy to share them if anyone is interested.

What happens if these farmers were to be taken off from this value chain? Obviously there will be  an impact on their livelihood. They might have to find some other employment or they might have to diversify to another agriculture crop. I am not in a position to talk about a real impact since the tobacco cultivation is still not banned. Therefore, in terms of an economic impact what is possible to assess is the perceived impact (foregone economic opportunity). To comment on that the household survey needs to be completed and I will write on this at a later stage.

an impact on their livelihood. They might have to find some other employment or they might have to diversify to another agriculture crop. I am not in a position to talk about a real impact since the tobacco cultivation is still not banned. Therefore, in terms of an economic impact what is possible to assess is the perceived impact (foregone economic opportunity). To comment on that the household survey needs to be completed and I will write on this at a later stage.

Qualitative discussions can only reveal perception information. Therefore, based on that, many farmers were not quite clear about what to do if they were taken out from the tobacco value chain. Some had confidence that the tobacco ban will never be implemented. Some were seriously considering protesting against it, if things get serious. However, some said that with the correct incentives they would diversify. From a research point of view and as the topic of the article suggests, I believe this group is the most important. Once incentives are identified, it will be easy to have a discussion with the farmers who do not have an option and those who would protest.

Talking to farmers and barn owners, it was clear that they look for a crop that has the potential to yield economic rents as tobacco does. They have a well-established value chain with tobacco, and the value chain that CTC is involved in has a well-functioning out-grower model. While farmers do have several crops on their minds, for example soya, they are afraid of the transaction costs.

Diversifying to conventional vegetables has its own drawbacks. For example, more of the same vegetable means higher supply and less price. At the same time the market discovery cost kicks in and most farmers do not want to face that. During the discussions and field observations it was noted that most tobacco farmers in Kalpitiya area grow chili and ornamental flowers. This might be an option for them. But to make a sound comment, that value chain needs to be studied well by the authorities proposing the tobacco ban.

Farmers who work with CTC demanded the same working arrangement that they already have. They wanted an out-grower model mainly with a guaranteed price and inputs supplied on a cost recovery basis. However, this might be an issue for farmers in Monaragala, Buththala and Wellawaya areas since they are very confident that no other crops can be grown without being attacked by elephants. While farmers can at least diversify in to another crop, barn owners might be in a difficulty since barns will be useless for another purpose as mentioned by them.

A pay out system (paying the economic cost of the barn for them to exit) is something that barn owners were interested in discussing. The initial qualitative research work notes that tobacco growers have little or no option left if the ban becomes effective by 2020. While some farmers suggest limited number of options, those have to be evaluated under experimental conditions.

For example, suggesting an alternative crop is simply not enough, they have to be tested with farmers under different soil and climatic conditions. It will not be a wise option to simply force farmers to diversify until incentives are clearly identified.

(The writer is an agriculture economist. He can be reached at [email protected].)