Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 12 August 2022 00:46 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Rohan Wijesinha

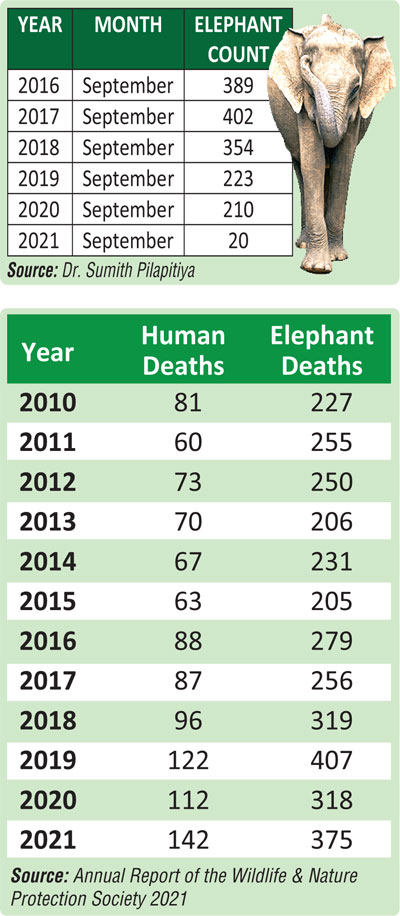

Current scientific data shows that elephant habitat in Sri Lanka has reduced by 15% over the last 50 years. It is an equally well-known scientific fact that when the habitat of a species is reduced, the species population declines.If the figures for elephant mortalities, from 2010 to 2021, are considered, then this is happening right now. 3,328 elephant deaths were recorded during this time. Whether there are 6,000 wild elephants in Sri Lanka today, as per a 2011 survey, or twice that number, at this rate of attrition, the continued existence of a viable breeding population is threatened.

Current scientific data shows that elephant habitat in Sri Lanka has reduced by 15% over the last 50 years. It is an equally well-known scientific fact that when the habitat of a species is reduced, the species population declines.If the figures for elephant mortalities, from 2010 to 2021, are considered, then this is happening right now. 3,328 elephant deaths were recorded during this time. Whether there are 6,000 wild elephants in Sri Lanka today, as per a 2011 survey, or twice that number, at this rate of attrition, the continued existence of a viable breeding population is threatened.

Add to this that current scientific research shows that there is a high mortality rate amongst calves, the forecast is bleak. Ina study undertaken at the Yala National Park by the Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR), it was found that 54% of all elephant calves died within twoyears of birth. The main reason – malnutrition. This is being replicated elsewhere too.

Let us not forget the human victims

In the 12 years referred to above, 1061 humans lost their lives too, mainly due to the increasing human-elephant conflict. There are several reasons for this but unplanned development ranks foremost. Sri Lanka needs development, desperately, but it should be planned aroundnot only the needs of the people of the area but also the natural environment and wildlife that may be sharing the landscape with them.

This lack of forethought has resulted in a serious loss of habitat for wild elephants, and the resulting loss of food sources drives them to seek sustenance in adjoining human cultivations. This results in the inevitable increase in human-elephant conflict, and deaths on both sides.

Electric fences are currently the best method for keeping elephants out of an area, but they must be positioned in the right place, between human settlement and natural elephant habitat.

The fences should be located at boundaries that the elephantsrelate to.At present, fences have been erected haphazardly, often separating DWC lands from Forest Department lands with wild elephants on both sides. Community and Cultivation Fences are the way forward, with them erected around villages and their cultivations, after all the prime necessity is to save human lives and crops.

The DWC claim that their community fencing projects have not worked. Yet CCR has achieved 100% success at the fences they have erected around over 70 villages in the North Central, Northwest and Southern Districts. So, what are they doing right that the DWC isn’t?

Sri Lanka needs wild elephants

Ignoring the culturaland religious significance in keeping healthy and viable wild elephant populations in Sri Lanka, and that they are a keystone species fundamental to the healthy existence of all of the other creatures of the forest, they are also a vital source of foreign exchange for the country.

Economists in Sri Lanka have estimated that a wild elephant is worth $11 million to the country if allowed to live to its full span of life (https://www.ft.lk/columns/A-cut-tree-a-dead-elephant-is-a-lost-tourism-dollar-in-the-future/4-709347). Tourism contributes 5% of the country’s GDP, and nature-based tourism constitutes a substantial part of that.

The Minneriya National Park is known throughout the world for its seasonal ‘Gathering’ of elephants, the largest congregation of Asian elephants in the World. Sadly, there is a tragedy playing itself out there too.Since the construction of the Moragahakanda Reservoir in 2018, there have been unseasonal waters released into the reservoir during the dry season that have resulted in a fluctuation of water levels. This has led to a reduction in the elephant population during the peak months.

Recent media reports carry the stories of a repetition of that which is playing itself out in Yala, with elephants being observed with poor body condition, and dead calves being found with malnutrition. The Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS) isfacilitating a special series of meetings, aptly titled ‘The Gathering’, for like-minded organisations, to discuss the present plight of the elephant and to decide on shared strategies to prevent their further elimination.

The first of these starting today, International Elephant Day, will be to specifically focus on the situation at Minneriya.

Is this the focus of the policymakers too?

According to the great chronicle, the Mahavamsa, in the 3rd Century BC the Arahant Mahinda, who brought the noble teachings of the Lord Buddha to this country stated: “O great King, the birds of the air and the beasts have as equal a right to live and move about in any part of the land as thou. The land belongs to the people and all living beings; thou art only the guardian of it.”

In fact, the people of this island have been extremely tolerant of wildlife, and elephants in particular. Wild elephants occupy 62% of the landscape of Sri Lanka, 44% of which they share with humans. This coexistence has endured for thousands of yearsbut changed dramatically in the last 50 years.

Do the policymakers of today still believe that the teachings of the 3rd Century BC are relevant for Sri Lanka?Or are they determined to let the wild elephant drift into assisted extinction?