Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 14 August 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The mediocrity in universities in Sri Lanka continues due to inept higher education administrators perpetuating low-quality programs by investing limited funds on educational curricula. The future is not rosy for Sri Lankan universities unless quality and rigour of research and teaching is drastically improved to be consistent with international standards

Sri Lankan universities are in turmoil and in deep trouble. University education is a critical component of development providing high-level skills and training in many professions. These trained individuals and skills drive the country’s  economy and support civil society. The unprecedented increase in demand for higher education in Sri Lanka especially after 1980, led to increase in the number of universities and private higher education institutions. But the expansion of universities in Sri Lanka was ad hoc and was not properly planned.

economy and support civil society. The unprecedented increase in demand for higher education in Sri Lanka especially after 1980, led to increase in the number of universities and private higher education institutions. But the expansion of universities in Sri Lanka was ad hoc and was not properly planned.

University standards in Sri Lanka declined due to a move to turn higher education institutes into teaching institutes which took priority over research. Universities failed to recruit qualified academic staff and private universities lured inadequately remunerated teaching staff from public universities. Major changes in teaching and research and updated pedagogical techniques to produce good learning outcomes for students are essential.

The telecommunications revolution in the 1980s opened the door for diversified forms of teaching , the use of the internet, effective design of curriculum and course content, a wide variety of learning approaches, such as guided independent study, project-based learning, collaborative learning, experimentation, whose importance has been realised now especially with the emergence of COVID-19. But these should have been introduced decades ago if we planned universities properly.

The mediocrity in universities in Sri Lanka continues due to inept higher education administrators perpetuating low-quality programs by investing limited funds on educational curricula. The future is not rosy for Sri Lankan universities unless quality and rigour of research and teaching is drastically improved to be consistent with international standards.

But the mission of universities has expanded greatly in recent decades because an educated populace is vital in today’s world with increasing importance of knowledge as a main driver of economic development. Knowledge accumulation and application are at the core of a country’s competitive advantage in a globalised economy. Sri Lankan universities sleepwalked into a time when universities must not just deliver education but drive short to medium term economic growth. Sri Lanka has experienced substantial growth of student numbers and the student profile has become more diverse. Sri Lankan universities must foster quality teaching to respond to the growing demand to ensure education leads to gainful employment and equip students with modern skills.

Evaluation of teaching is an important element. Prestigious universities conduct anonymous evaluation of teachers. At Monash University, Australia and all other campuses, a teaching score of 3.8 out of 5 must be reached for each subject taught to consider teaching to be satisfactory. Remedial action will be applied to teachers who fail to achieve satisfactory scores. Good teachers inspire students to express independent opinions and encourage cross fertilisation of ideas on socially important issues relevant to the nation. University graduates in Sri Lanka face a challenging future with greater uncertainty and universities must prepare students to be linked to business and industry and global demand.

The tragedy in Sri Lanka is that academics have to constantly grapple with self-serving, politicised attitudes and Ministers totally inept in developing ideas to maintain rigorous university standards. Creating leadership in higher education with a towering intellect and not a tuition master to put universities on a sounder footing is a must. A recent proposal to establish a cricket field in Homagama with $ 40 million is a reflection of this utter stupidity and the inability to think by the Brahmins of higher education in Sri Lanka when higher education cries desperately for more funds for infrastructure, laboratories, more highly qualified staff, and funds for scholarships to students and international links.

I quote the following from 18 July 2020: According to Open University Teachers’ Association President Dr. B.D. Witharana, the Open University is facing a critical financial crisis for the past one year, with a serious reduction in funding. The Treasury has provided only Rs. 150 million whereas salaries of permanent staff for a month amounted to Rs. 190 million. As a result, the OUSL has been forced to spend its own reserves earned through student fees to cover up the shortage.

Meanwhile, he said relying on student fees to meet university expenditure pushes the OUSL towards privatisation and research activities of the university have been halted due to lack of funds. Witharana further noted that the OUSL serves more than 40,000 students. This is the reality of the situation in Sri Lanka. Political interference poses an existential threat to universities in Sri Lanka and to society in general.

Universities’ research and economic development

Universities are not conveyer belts to grant degrees but must be centres of excellence to equip candidates with the necessary tools and methodologies to pursue rigorous and exhaustive research that contribute national development. For Sri Lanka to move into a high income economy, we need to realign educational systems to support research and innovation.

Universities as essential part of the broader society must engage in socially relevant research such as dengue, COVID-19, climate change, poverty and hunger, food security, water scarcity and kidney disease. Technological innovation co-evolves with economic, social and political systems. Research on wind and solar technologies, and digital technology, climate change, health issues and multidimensional poverty is essential for Sri Lankan researchers to engage with international partners who work on these issues. Research funds directed towards empowering the next generation of researchers in transformative ways, can contribute to development without undermining either excellence or equity or teaching quality.

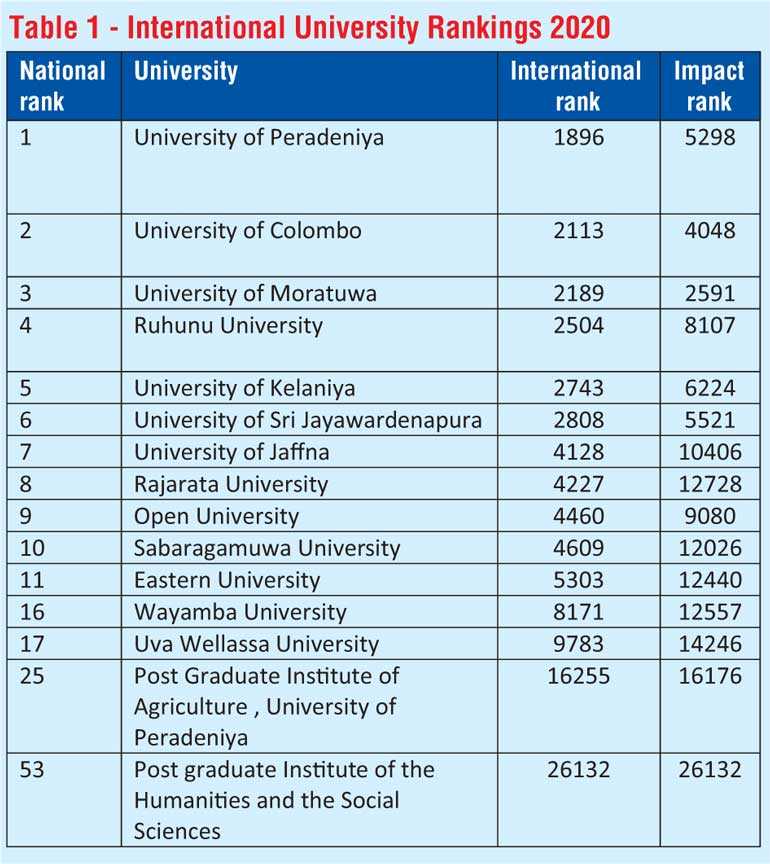

Sri Lankan universities have failed in international rankings which signals to the world that our universities are not up to standard (see Table 1). University research in Sri Lanka lagged behind that in many Asian countries. The heavy investment on infrastructure – new buildings, auditoria and laboratories is easy but to make use of modern laboratories, you need well-trained researchers.

Building research links with universities and academics in developed countries is one way to improve the expertise and prestige. Such collaboration help tackle disease, deal with climate change and develop new technologies. Sri Lankas’ research output and quality are shockingly low. Countries which are integrated more closely with the global economy experienced higher economic growth, a reduced incidence of poverty, a rise in the average wage, and improved health outcomes. The countries that benefited most from integration with the world economy achieved the most marked increases in educational standards.

Sri Lanka spent an average of 2.53% of GDP between 1973 and 2015 on education. In 2018 it was 2.11% of GDP. The world average in 2018 was 4.18% of GDP. Less developed countries invested 0.23% of their gross domestic product in research and development in 2016, but the world average was 1.86%.

The global university system is the epicentre of cutting edge research on some of the most intractable problems in the world. University of Oxford is the first to develop a cure for COVID-19. Scientists at Oxford University conducted trials of the drug dexamethasone which is hailed as a major breakthrough in the fight against COVID-19. For less than 50 euros ($A90), the steroid can treat eight [COVID-19] patients and save a life, according to Prof. Martin Landray, an Oxford University professor who is leading the trials. In the University of Queensland (UQ), Australian scientists created their first vaccine candidate using the platform in just three weeks. The UQ was partnering with Dutch company Viroclinics Xplore. Clinical trials are being conducted right now on human volunteers. Human trials have already begun with a sample of volunteers.

Similarly, Monash University, Australia is developing three vaccine candidates using a new vaccine development approach known as mRNA. These messenger RNA molecules "code" for viral antigens. Once injected, antigens are made inside our body where the immune system is trained to recognise them – and protect us if the virus invades later.

Monash also conducts research on dengue fever. I published an article on 18 July 2017 in Daily FT (please read the full article) titled ‘The dengue menace in Sri Lanka: Will Sri Lanka ever get this right’. I quote the following from that article: “The recent media reference to a bacteria being imported from Australia to destroy the mosquito and the larvae refers to research done at Monash University, Australia which is developing a natural method using the Wolbachia bacteria to stop the mosquito from being able to transmit the virus which can reduce the incidence of dengue. This is in the experimental stage and is not available in a limited way. The research is led by Institute of Vector-Borne Disease at Monash University Director Prof. Scott O’Neill. ‘Eliminate Dengue’ research, transfers the Wolbachia bacteria into Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and when Wolbachia is present in the mosquito it reduces its ability to transmit the dengue virus.”

This is being presently tested in Sri Lanka. But my question is, “Where are the Sri Lankan universities in this kind of research when thousands of people are affected by dengue every year in Sri Lanka and not in Australia?”

Sri Lankan universities can benefit from financing research through grants similar to processes adopted in Australia, Malaysia and Singapore. Such strong granting institutions can distribute funds for research based on competition. The Australian Research Council (ARC) provide National Competitive Grants to support the highest-quality fundamental and applied research and research training through national competition.

The ARC supports high quality research leading to the discovery of new ideas, facilities and equipment that researchers need to be internationally competitive, training and skills development for researchers and incentives for Australia’s most talented researchers to work in partnership with leading researchers throughout the national innovation system and internationally, and to form alliances with Australian industry. Universities in Australia received 12,477 competitive grants during the 2014–2016, representing an investment of $5.1 billion.

Sri Lankan universities are slipping down the international rankings which is unacceptable in an era of globalisation (Table 1). Many academic staff members have no research to show despite being in long-term employment. In order to get funding, a university will have to concentrate on disciplines where it does best and where it is strong. High level of international collaboration in research and publication, more international students and more international academic staff that engage in international cooperation is imperative.

Faculties have failed to face pressures to publish, attain good rankings, and attract research funding, Knowledge-based economic development societies need academic freedom and institutional autonomy to support scientific reflection and knowledge production. Universities’ need autonomy, academic freedom, and impartiality. Appointments to prestigious academic positions such as professors must be based on utmost merit. Compromise on these values will debase the standard of scholarship. The most recent global evaluation of universities show that only Peradeniya University was mentioned and other universities were not even mentioned (see Table 1).

Table 1 shows that University of Peradeniya was ranked 1896 and University of Colombo was ranked 2113. The others are self-explanatory. The impact rank is 5298 for Peradeniya University and 4048 for the University of Colombo. This implies that the contribution of universities to social development in Sri Lanka is abysmally low and not worth talking about. New universities such as Wayamba and Uva Wellassa were ranked 8171 and 9783 respectively. After about 70 years of development of higher educations, this is the result. Do we want more of universities like this? You know the answer.

Increasing the number of universities in Sri Lanka

Increase in enrolment of students is necessary to provide opportunities to all those who qualify to enter the university and I believe it is a birth right. But critical pedagogy and robust research can be undermined by this rapid expansion in tertiary student enrolment without equivalent improvement of university resources. We simply open the floodgates to mediocrity.

The plan to establish universities in every electorate will distort the nature of higher education, the quality and performance, waste limited resources and lower academic integrity and credibility. Having universities in Kalutara, Galle, Matara and Hambantota along the southern sea coast reflects the irrational nature of Sri Lankan thinking on higher education. Universities are not tourist hotels that should be built along the palm fringed beaches in the southern coast of Sri Lanka. Some of the members of Parliament who clamour for universities in their own electorate may not even have GCE ordinary level and we are therefore not surprised by these irrational ideas. More universities can lead to poor regulation and creation of duplicate programs under different titles which adds to the oversupply of unemployable graduates.

Prof. R.P. Gunawardena recently published an article against more universities in Sri Lanka. I agree with some of his arguments. Expanding existing universities with good infrastructure and highly acclaimed staff should be the priority both to enhance teaching and foster research.

Politics and autonomy in universities

Intellectual elites and academics can shape Sri Lanka’s universities better if granted autonomy to pursue their intellectual goals with little interference. Sri Lankan universities, if provided space for free enquiry can generate innovative ideas to meaningfully engage in national economic development. Universities should be accredited or ranked not only on their research output or teaching quality, but also on how well they contribute to society.

Infusing political and ideological interests, using irrelevant agendas directed towards specific audiences can make universities even becoming centres of indoctrination as was revealed recently in the operations of the Eastern University. The politicisation of higher education extends to political involvement in the appointment of university vice chancellors. Sri Lankan universities have risen through a political process and not merit thus establishing a revolving door between the political sector and higher education.

Increasing universities must be done with great care not to damage the core business of universities such as research and should transcend traditional disciplinary limitations to create an adaptable workforce. Planning for more universities must be done at least for the next 10 years. But decisions on these must be done by the total university community comprising vice chancellors, deans, heads of schools, professors, other academics and students and the wider society.

This group must decide on the number of universities, courses and curricula in each university, locations of universities, international collaboration and any links with other elitist universities including the budget without allowing these critical decisions to be made at the whims and fancies of politicians. If the academics are strong, they should have the capacity to get the politicians on board. The centre of gravity of decision making should shift to the university system and not exclusively to politicians.

The so-called brain drain can change the skill structure of the labor force, but it can also generate remittances and other benefits from expatriates. It depends on how the country conceptualises brain drain and the policy environment. I have personally donated more than Rs. 1 million worth of books to the Post Graduate Institute of Agriculture at the Peradeniya University and the Wayamba University. I have also arranged senior fellowships, Post-graduate scholarships and conference support for some of my academic colleagues in Sri Lanka.

I am aware that many academics do this to their colleagues and the total may be substantial. These academics are also involved in major inter-university and industry collaboration with Sri Lankan universities. In total these benefits may be very high but of the current emphasis is on sending our mothers and daughters to the Middle East to earn a fistful of dollars who can be raped or even killed. Which is preferable? You know the answer.

But politics in higher education is endemic and hence it is difficult to promote academic integrity. Political involvement in universities is not new but existed since the 1960s at least. In the 1960s, the number of admissions was increased by around 800 in a particular year in order to accommodate the son of a powerful personality in Sri Lanka. This particular batch was given the name of the student (G…… batch) who was so admitted and this was common knowledge.

About a decade or so ago, the then Minister of Higher Education would regularly telephone the legal officer of a particular university, advising her to expedite the promotion of a particular lady, who happened to be his former girlfriend, although the Minister was s married.

I.M.R.A. Iriyagolla, the Minister for Education (and Higher Education) said the following on university lecturers which was the headline in the front page of Dinamina in 1969 (cannot remember the month and date): “Sarasavi adurange hossa bima ulaw.” This reflects the toxic atmosphere that existed between the Minister and the university system, even 50 years ago and it is not better now.

I remember that in the 1980s a particular Vice Chancellor brought the name of Lalith Athulathmudali to the University Senate to be awarded a Hon. D.lit in law. Fortunately the request was knocked down because Peradeniya University did not have a Faculty of Law at that time. This is simply quid pro quo.

Vice chancellors are appointed on political criteria. Think of Vice Chancellors like Prof. Ivor Jennings, Prof. E.O.E. Pereira, Prof. Nicholas Attygala, Prof. Walpola Rahula and in recent times Prof. Arjuna Aluvihare and Prof. Savitri Gunasekera. If we have vice chancellors who are half as good as them, we will be shining on the world academic stage.

At present vice chancellors are just nominees of the education minister and the minister himself is a mere political lackey devoid of vision, intellect and competence. I once met a Sri Lankan vice chancellor about 15 years ago at the Sydney Airport, drunk. Sri Lankan vice chancellors must be above board and beyond reproach.

Responses and consequences

Encouraging the establishment of private tertiary education institutions to help soaring student enrolment should not be discouraged. For new universities, a major challenge is finding appropriately qualified lecturers. Also, many new universities located in rural areas have less access to adequate amenities and facilities. Private higher education institutions operate commercially with dubious quality. Thus, every measure taken to increase quantity will undoubtedly lead to quality being sacrificed.

SAITM suffered its fate because it was never transparent and the wider academic community was not involved. It came like a night thief supported by a few politicians. Let us not make this mistake again. It is imperative the Government makes private universities are affordable to even the poorer sectors. Everyone should have the same opportunity to better themselves through education, which will pay off in the long term for the country. It is essential for the Government to provide good loans to poorer sections of society so that there will be no inequity in higher education and the opposition to private universities may thus be diminished.

Ensuring quality in Sri Lankan higher education institutions must now, more than ever, be considered a priority provided with adequate resources. Sri Lankan leaders must understand these complexities and appoint a respectable academic with good credentials and insights as minister of higher education to put the university system in order before the storm breaks.

(The writer is attached to the Monash University and can be reached via [email protected])