Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 8 July 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

‘Mining’ is defined as the extraction of valuable minerals from the earth and it is undertaken mainly by using two techniques, namely surface mining and underground mining. Surface mining is the most common type of mining (85% of all mining is surface mining), and is the only technique used for heavy mineral mining.

‘Mining’ is defined as the extraction of valuable minerals from the earth and it is undertaken mainly by using two techniques, namely surface mining and underground mining. Surface mining is the most common type of mining (85% of all mining is surface mining), and is the only technique used for heavy mineral mining.

Sri Lanka, despite being a small country, is well known for its non-metallic mineral resources. When evaluating the mineral resources of Sri Lanka, it is apparent that black sands or heavy minerals stand out as being the group that has the greatest potential to deliver globally significant production.

As revealed from mineral investigations performed by the Geological Survey and Mines Bureau, Sri Lanka’s mineral resource base consists primarily of industrial minerals. Of these industrial minerals, heavy minerals (mainly ilmenite, rutile, zircon, garnet, and monazite) are amongst the most abundant minerals with high economic potential found in Sri Lanka.

Our nation could develop and create an extremely efficient and attractive foreign investment environment for the mining sector supported by the right policy and regulatory regime, developed by looking at successful mining jurisdictions like Australia, Canada, Finland, USA, etc. through a well-coordinated and strengthened local government framework.

Value addition

There is considerable debate and argument within the local mining industry, mainly among the regulators, academics, policymakers and the miners about the process of ‘value addition’ prior to export of minerals from Sri Lanka. The purpose of this article is to promote both arguments in favour and against, amongst various stakeholders and to elicit a productive dialogue.

Value addition or beneficiation could be defined as a way by which a mineral resource is subjected to a scientific process (physical or chemical or both) that would result in a product of enhanced economic value compared to its original value. Mineral processing, beneficiation or value addition will involve different processes depending on the primary type of raw material.

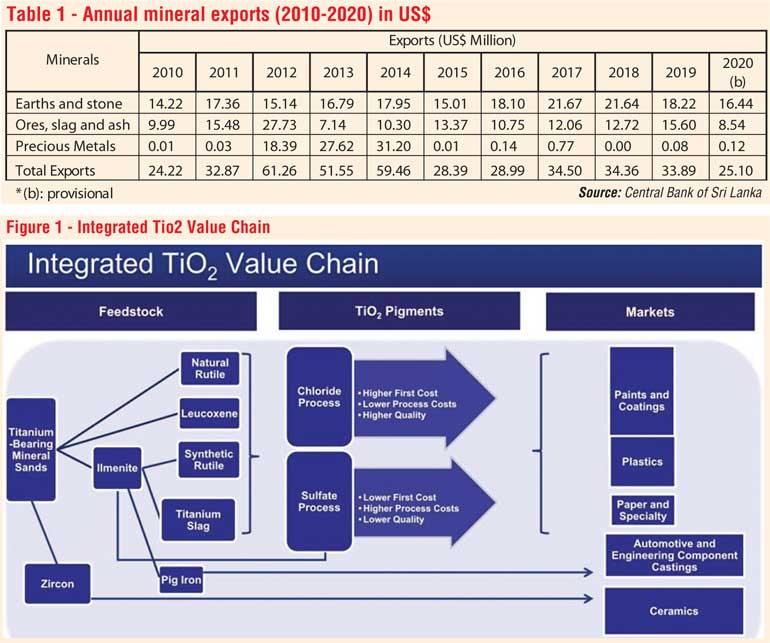

‘Value addition or beneficiation’ to heavy mineral sands in Sri Lanka is still at a primitive stage and the export volumes and returns to date do not show any kind of consistent pattern to the world market. Table 1 depicts the annual returns generated through various groupings of mineral exports in the last decade.

Sri Lanka currently exports minerals to buyers in China, Japan, Singapore, United States, South Korea, India, Italy and the United Kingdom, etc. for further processing as Sri Lanka does not have any developed primary resource-based industries operating at present.

Global minerals industry

Primarily, the global minerals industry is vertically integrated with a well-established ‘value chain’. Every step of the way from raw material to an end-user product is a process of ‘value addition’. Miners add value by turning sand or rock (raw material) into saleable products for the next step of the value chain and thereby incurring massive capital and operating expenses. Mining companies rarely sell ‘raw material’ but always complete some form of value addition through separation of the mineral components into distinctive minerals.

Mining entails spending huge sums as capital and therefore, the extractive or mining companies sit at the beginning of the value chain. The resultant products are then sold to another intermediary and the products’ saleable value increases from one intermediary to another until it reaches the consumer.

To put it simply, there is a value chain, and mining companies get minerals to a point in the value chain, and the ‘value add’ companies get the products to further points up the value chain. It is indeed rare for one entity to be involved in both the mining, extraction as well as value addition of minerals in the different stages of the value chain.

In the case of heavy mineral sand, value addition is centred round the production of Titanium dioxide (TiO2) pigments in the form of rutile, ilmenite, etc. It is mainly produced via two commercial processes namely sulphate and the chlorination processes through upgrading the naturally occurring mineral ore by removing impurities (see Figure 1). Zircon is generally separated by electrostatic separation to obtain high-grade TiO2. On the other hand, the traditional methods for producing Synthetic Rutile (SR) from ilmenite are smelting, Becher, hydrochloric acid leaching and sulphuric acid leaching processes.

According to Minerals Yearbook, USGS (2017):

Escalating market demand

By studying the above reported figures, there is a necessity to expand the production of minerals to cope up with the escalating market demand. It is obvious that the implementation of value addition in the mining sector will play a crucial role for economic recovery, growth, and transformation. Moreover, it will bring in more foreign revenue, generate employment opportunities, boost Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross National Product (GNP), lead to developing of modern allied industries, empower a variety of business prospects, and act as a catalyst that attracts FDIs to setup downstream industries to use the value-added mineral resources.

The World Bank report (Oil, Gas and Mining unit Working Paper, April 2014) pointed out that the Human Development Index (HDI) – including its education and health components – show higher scores for countries rich in mineral resources other than oils. The same is true for the education and health components of the HDI.

The presented data in the report suggests that mining dependent low- and lower-middle-income nations have initiated the long road to bridge the disparity gap and increase accessibility to quality healthcare and education. Furthermore, countries which utilise the utmost advantages and opportunities afforded by the demands of the mining trade to establish spinoff industries are the ones most likely to see sustainable growth.

Large mining projects often bring about several infrastructure developments (including transportation which is essential for the operations), which can then be accessed by other industries and the public. Industrialisation surrounding the mining sector not only boosts the local direct job opportunities but also indirect avenues through the multiple effects of industrialisation.

Several corporates are either voluntarily or due to government legislation offering to assist programs which uplift the living standards of local communities. This assistance is mainly via corporate social responsibility programs, local infrastructure development projects, foundations, and targeted tax payments. These substantial positive attributes will have an impact on the Sri Lankan economy as a whole.

Challenges in enabling practical success

Even though the theoretical aspect of value addition appears to be convincing and promising, the challenges in enabling the practical success of this industry in Sri Lanka prevent the progress of its execution momentarily. The process of establishing a value addition commerce is a staged and long-term process to obtain the utmost benefits out of it.

Regardless of having various significant deposits in our country, supplementary value addition is impeded due to several factors. These include the requirement for large capital investments with a long recovery period, high energy requirements, expertise and human resources, shortage of supporting chemical and manufacturing industries, unavailability of suitable facilities for recycling and disposal of waste, limited market demand in Sri Lanka, lack of R&D, unexplored mineral deposits, unavailability of well-defined policies, inadequate government intervention to the mineral industry, the inefficient utilisation of economically valuable mineral resources, etc.

Moreover, Synthetic Rutile can only be produced with a specific TiO2 content mineral through an extremely expensive, complicated, risky and highly-pollutive sulphate process (TiO2 content of at least 65% is required for the chloride process). Furthermore, SR/TiO2 pigments production is an extremely capital-intensive project. This value addition method would require large amounts of capital investment, large amounts of specialist coal for power and high-end technical expertise before a SR/ TiO2 pigment factory could even be considered. It is vital that feasibility studies are done on the availability of the required volume of high-grade TiO2 mineral sands in Sri Lanka that are suitable for SR production.

The existence of chemical industries, ancillary industries, etc. and the availability of linkages that facilitate other sectors to be tied into value-addition processes are other key elements for the cost effective production of value-added minerals that enable them to be exported at competitive prices.

The deficiency of such processes in Sri Lanka would drive the value addition industries to trade the products with additional cost. Value addition processes require certain infrastructure, such as transportation, water supply and electricity, etc. Mining and allied value addition industries are mainly led through electrically driven processes and therefore demand a substantial amount of power.

On the other hand, finding a suitable location to locate the factories and the impacts of using chemicals, might be a challenge due to the high population density in Sri Lanka. In many countries, this type of industrial setup is placed in highly remote locations or deserts to ensure that there is minimal impact on human settlements.

These cumulative factors will add an extra burden of cost to the setting up of manufacturing plants, well before ensuring the viability to commence the value addition process. These concerns may tempt mining companies to conduct further studies before devoting large capital to set up value addition industries within the country by further investing capital. They would require assessing the commercial viability of these projects, which includes investment, production cost, electricity cost, pollution management and most importantly finding the right market and strategies for market penetration.

Exporting heavy minerals

Considering the above concerns, a thorough due diligence should be carried out on the suitability and viability of such projects and in the interim, we should consider the promotion of exporting of heavy minerals to countries with well-established factories and support services. Australia, being one of the top mineral producers in the world, exports most of its extracted resources to overseas markets in raw mineral forms. It is stated that Australia converts less than 1% of its iron ore into steel within the country.

For such value addition industry to thrive, the Government and the regulators should formulate policies and procedures to promote and establish such operations in Sri Lanka by encouraging the private sector with the necessary capital and the know how to invest. Such encouragement should be coupled with long term policies and regulations indicating consistency and long-term vision for such industries that do not change from government to government, as investments of this nature can be large and recovery periods unusually long.

A readily available alternative in the short to medium term is for Sri Lanka to export its heavy minerals to countries with well-established industries. On the other hand, once the extractive companies start work here, and upon the exploration of sufficient potential resources, the value addition companies will follow for their industrial setup– but this is a long term, staged process and as stated above, the extractive companies are not purely value-addition companies, so the government must attract them with irresistible investment policies.

Sri Lanka can adopt well formulated policies and guidelines to encourage private entities in order to set up value addition plants in Sri Lanka. This should be supported by introducing incentives schemes, public-private partnerships to encourage joint ventures, as well as obtain foreign expertise and technology to become a significant contributor to the global mineral market.

A comprehensive cost-benefit analysis applicable to specific minerals requires to be undertaken with the participation of industry players before formulating policies. Also, an appropriate fiscal and tax structure must be put in place to manage the large revenue inflows in a more responsible and transparent manner. The newly-proposed Sri Lanka Inland Revenue Act does not include a single paragraph or a sentence on mineral extraction or the tax treatment of such entities.

(The writer is a visiting lecturer at the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka and is also a researcher on the mineral industry.)