Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 14 January 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Three-wheelers have become a popular mode of transport in the urban, rural and state sectors of the country. This informal transport sector has boomed throughout both the developed and developing worlds, bridging the gap of inadequate, inefficient and ineffective public transport services and  delivering a faster means of transport.

delivering a faster means of transport.

The urban residents who are negatively affected by intolerable levels of traffic and congestion and who are unable to afford private transport create a heavy burden on the sector (Cervero, 2000). In this regard, powered two- and three-wheelers are becoming one of the main means of transportation both for people and goods, particularly in developing countries, and are attracting an increasingly varied user population while three-wheelers (TWs) have been identified as a popular mode of public transportation in low- to middle-income countries (World Health Organization-WHO, 2017).

Hiring three-wheelers has become a major means of self-employment in Sri Lanka. The country is one of the largest markets for TWs (The Economist, 2014). It has been pointed out that the number of three-wheelers doubled between 2005 and 2010 (DoM Traffic. 2011). The number of registered three-wheelers in Sri Lanka was 766,784 in 2012, which is 15.7% of the total vehicle population (DoM Traffic. 2015). From 2004 to 2012, the number of registered three-wheelers in Sri Lanka increased by 260% and by the end of 2016, there were 1,062,447 registered three-wheelers.

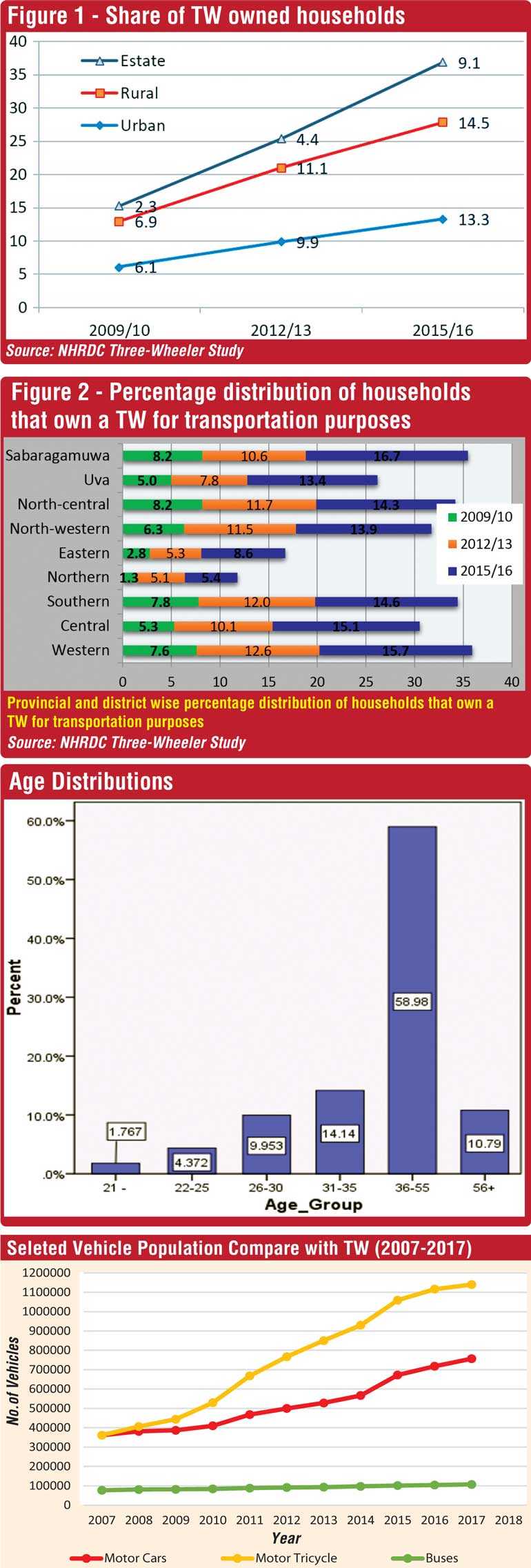

Growth in the number of three-wheelers is greater than in any other category. It has increased by 261% since 2010. From 2010 to 2016, the share of TW-owned households in the country increased from 6.5% to 14.1% (DCS, 2018a). The growth of the number of TW-owned households is recorded at 188%, which is much greater than the growth of car-owned households (55%) and bus- or lorry-owned households (40%) (DCS, 2013, 2018a).

There is a clear variation in sectoral, provincial and district layout. The highest number of three-wheelers by the end of 2016 was registered in the Western Province (352,540), which was one-third of the total, followed by 140,823 in the Southern Province and 135,791 in the Central Province. The least number of three-wheeled vehicles registered (1,331) was recorded in the Eastern Province.

Once the share of TW-owned households was taken, as shown in Figure 1, the estate sector demonstrates dramatic growth (from 2.3 in 2010 to 9.1 in 2016), with a more than 295% increase. This increase is 110% and 118% for the rural and urban sectors respectively (DCS, 2013; 2018a).

Issues arising in the labour market due to increase of three-wheelers

Sri Lanka is faced with an acute shortage of labour at the skilled and semi-skilled levels. There are multifarious jobs in the construction, manufacturing, tourism and hospitality sectors creating employment opportunities for a lot of young energetic people in the local and international job market.

However, many young people under-employed as three-wheeler drivers not only waste their productive labour but also tend to get addicted to a life of drugs and crime. The economic and social opportunity cost is much higher than the benefit. Therefore, there is an urgent need for finding strategies to move the productive spirit of the country into better-paying, low-stress productive jobs which ultimately lessen the acute manpower shortages in booming sectors of the country.

Overview of three-wheel jobs: Age, education, income and other scenarios

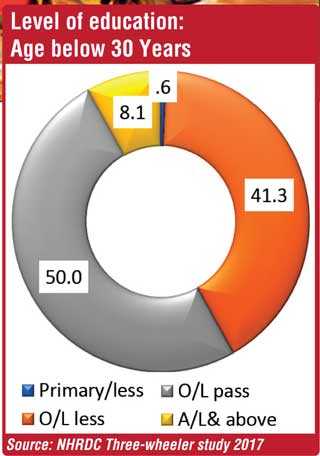

It was revealed that approximately 16% of TW drivers were below 30 years of age and more than one-third of them were below 35 years. Their education background showed that the majority of TW drivers had completed the Ordinary Level, with 50% of those below 30 years having passed their Ordinary Level. Half of the sampled young population acquired an Ordinary Level qualification and 8% of them have completed the Advanced Level or higher.

It is a preferred mode of transport and an employment source for both rural and urban communities because of the low cost, ready availability, convenience, road manoeuvrability and popularity as an ambulance for the rural poor.

It has been well acknowledged that there are significant negative externalities: traffic congestion, disorderly operations, unfair practices and accidents that harm public safety and welfare. Thus, the deregulation of the TW industry is one of the crucial facets is needed to be addressed to deliver significant benefits to society.

According to the study’s findings, TWs drivers earn a considerably higher level of income compared to other forms of self-employment. Their average income is Rs. 39,000, with an income range extending from a minimum of Rs. 4,800 to a maximum of Rs. 140,000.

The vast majority of TW drivers have bought TWs using leasing or loan facilities. This indicates that less restricted leasing facilities seemed to have led to a boomed in TWs in the country on the one hand and created a considerable market for financial institutions on the other.

Where rules and regulations are concerned, the majority of TW drivers have fixed metres in their TWs. However, the widely practiced pricing strategy is ‘driver driven’. The TW market has been converted into an oligopoly partly because of information asymmetry and partly because of park registration.

The advantages of the emergence of TWs are the flexible working hours, a chance to support the family, a good source of income, a source to make new friends and also a very effective method of networking.

The most highlighted disadvantage of TW driving is the lack of social recognition for drivers. A lack of social acceptability, income and job security are the major issues faced by TW drivers.

According to the study’s findings, almost everyone in the field agrees with the Government’s efforts to enhance the lifestyles of TW drivers.

It was found that the majority just agree with all the rules and regulations proposed by the Government: Minimum age, identity card, uniform and a receipt handed to the passenger. This implies that they would probably not oppose the policies, provided that there were no costs imposed on them. However, it was evidenced that they are completely unaware of the need, importance and possible benefits of such implementations.

According to the findings, a little less than half of the TW drivers would like to quit their job if they had viable alternatives. The majority of those who wanted to quit were young married males. More than 90% of TW drivers who wanted to quit their TW job for another occupation were those who had completed their Ordinary Level exam. The data clearly indicates that the young who have been excluded from the formal labour market due to a lack of opportunities for the lower belt, have involuntarily been pulled into the TW sector. Further, it was found that most TW drivers wanted to have vocational training through part-time courses and training during the weekends.

The percentage of TW drivers who admitted that they used alcohol or smoked was quite high among frictional TWs. In contrast, risky passenger transportation is quite high among lifetime drivers.

The factors that influence TW drivers to choose an alternative livelihood strategy are found in the preference of being employed in another trade and is positively related to the level of education: the more educated drivers are, the more likely they are to quit. TW drivers who spend their waiting time reading newspapers are more likely to give up a TW job.

Policy implications for redeployment

Developing effective macro-level policies is important to absorb this energetic labour into productive economic activities. Appropriate and timely demanded skills should be developed through participatory trainings with the support of service or the contribution provided by TVET bodies.

Study findings primarily showed that empowerment programs should focus on young and married people. But their education background showed that the majority had only completed the Ordinary Level so they did not meet the formal labour market requirement for white collar jobs.

Moreover, spending of more than 92% of income to fulfil lower order needs implies that they have not fulfilled basic lower order needs. Therefore, if anyone from the group is to move into entrepreneurial capacities they may require rigorous sociocultural and economic upliftment.

The frictional TWs prefer regular, stable and less risky operations. Again, this suggested that entrepreneurship may be challenging for them because they seem reluctant to bear any risk. Thus, the entrepreneur culture should be developed before any policy intervention.

Policy implications for regulating the sector

Regulate best practices

The conflict between the practice of regulating (i.e. meter fixing, etc.) and the actual behaviour implies the mismatch between implementation and effectiveness of newly-imposed regulations. For instance, it seems that TW drivers have fixed metres merely as an escape strategy. Further, public trust in the meter function keeps deteriorating. This demands an effective regulatory body to monitor sector and fare regulations.

The authorities must regulate best practices (training, knowledge, awareness, age, advanced driving experience, etc.) which suits the given locality and can be adopted as entry qualifications for the industry.

Minimise information gaps

Centralisation - in the form of a government, semi-government or private intermediating centre can act to minimise information gaps, reducing transaction cost and also increasing consumer welfare (formulating a fare index, displaying a per kilometre price in the vehicle, informing the starting price and a per kilometre price at the time of online booking, rating TW taxies according to customer or society friendly service status are some of the best practices in the world).

Action has to be taken not to stop but to improve loyalty and the quality of the service with necessary regulations. Most of the sources show that there is no scientific base to conclude that there is an excessive number of TWs in the country.

Rigorous studies should be done in order to find an alternative transport service and productive job options for the youth. This is mainly because TWs provide an attractive employment option for rural populations, as well as high returns for people who lease them out. In addition, TWs provide vital mobility on rural roads that lack conventional transport services (even for transporting goods, access to maternal healthcare and transport for people with disabilities). Therefore, a disaggregated level (or region specific) of policy implementations would be more appealing.

Three-wheeler service has to be regulated as a profession

Driver-related factors may be controlled by developing a TW taxi service as a profession. They would be trained to maintain the profession. TW drivers should be tracked through comprehensive internship and follow-up training. It can be recommend to make it compulsory to have a NVQ taxi driver certificate or another skills certificate to prove their proficiency.

Appropriate social security network should be established

A lack of social acceptability. Income and job security are found to be the major issues faced by TW drivers. Furthermore, TW taxies put no burden on the Government’s Budget and it is a vital means of transport for the poor. Therefore, it is important to create a suitable social security network to improve it as an accepted profession.

Key action points to be executed

Taken as a whole, the Government should pay attention to implement the key action points mentioned below to increase the positive impact and minimise the negative impact to the economy as well as society.

A collective effort in mitigating this risk

According to study findings, even without knowing the need, importance and possible benefits of such implementations, the majority agreed with all the rules and regulations proposed by the Government. That is to say, the vast majority are not properly aware of the benefits of newly implemented regulations.

Further, there is a risk of politicising the regulations stressing the negatives by one party and positives by another. Thus it is mandatory to pass the complete information on impact of such policies on developing TW taxi service as an accepted profession.

Misconducts in TW sector cannot be taken separately. Especially, using of TW drivers as information providers may work as an official link for them to peep into the underworld providing unofficial license to support illegal activities. Thus, there must be a collective effort in mitigating this risk.

Key action points

Taken as all, Government should pay attention to implement key action points mentioned below to increase the positive impact and minimise negative impact to the economy as well as in the society.

Develop TW taxi service as an accepted profession

Upgrade selected TW and TW drivers toward tourist guide cum professional taxi drivers, enabling them to support the tourism industry

Proposed policies of minimum age, identity card, uniform, and receipt to the passenger (using meter) should implement by a responsible authority

Preventive action to school levers through adapting new rules and regulations will be most important. Age limit, compulsory NVQ qualification and industry experience etc. Within the school system and TVET should have proper career guidance system to direct youth for productive sectors instead to TW Make available short term NVQ training programs for TW drivers to gain additional qualifications. It will be help them to further increase the family income as well as some sort of solution to skilled workers shortage in the country Effective regulatory organisation need to monitor and implement policies in the sector

(Note: This article is written based on the facts and findings of research which was conducted by an appointed study committee featuring expertise from the University of Sri Jayawardenepura and the National Human Resource Development Council of Sri Lanka. The full research report will be available on the official NHRDC website.)

(The writer is an Economist in the Field of Human Capital and the Director of the Human Resources Development Council of Sri Lanka. He can be reached via email at [email protected])