Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 5 February 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

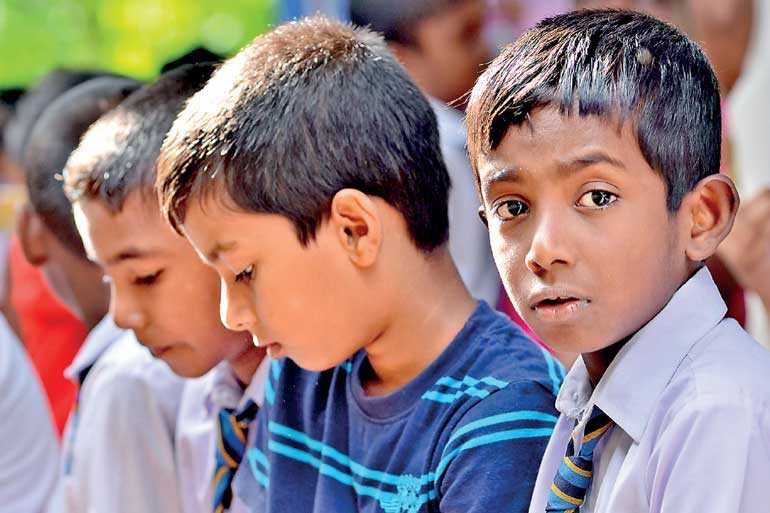

Much of the existing methods of instruction focus on grammar and exams, whilst foregoing adequate training in soft skills and spoken English. Students will often pass their written exams yet remain extremely diffident when faced with the prospect of conversing at length – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

These were the words uttered by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike to a crowd that had gathered near his ancestral home after his return from Oxford in 1925.

As the son of Sir Solomon Dias Bandaranaike, the ‘maha mudaliya’ of the Colonial administration, the young Bandaranaike had been groomed by his father to enter into a prestigious career in civil service. After being taught by a British tutor, studying at St. Thomas’ College and finishing his undergraduate studies at Oxford – it is hardly surprising that S.W.R.D. felt more comfortable speaking in English. This may not have been unusual for the time as English was a language reserved for the elite. Whilst Bandaranaike was later able to learn Sinhala, give great speeches in the language and become Prime Minister – the fact remains that the English language (and who was able to learn it) represented a certain stratification of society.

Has much changed?

Technology and rapid development have granted an unprecedented level of access to educational resources and interconnectivity. And yet a divide still persists. The English language is still widely perceived as part of the ‘Colombo elite’ – out of reach for many ordinary people. Education is often highly valued in Asian cultures, and Sri Lanka is no exception. Parents will spend eye-watering amounts of money on private tuition and international schools to provide their children an advantage in life. This has invariably led to a greater disparity in the country, where quality English education remains a privilege for those who can afford it.

Whilst English is officially described as a ‘link language’ in the Constitution (after the 13th amendment), it does not seem to have reached its stated potential. For a language to be effective as a ‘link’ between ethnicities and classes, it must be far closer to ubiquity than scarcity. A link language is a language systematically utilised to facilitate communication between groups of people who do not share the same native language/dialect. The fact that English ostensibly remains limited to a subset of the population (and out of reach for many of those living in poorer/rural areas), prevents it from fulfilling the role it has been given in the Constitution.

In the search for identity in a newly independent land, Sri Lanka strove to reinvigorate its culture, tradition and native languages. Such policies were arguably much-needed following the erosion of native culture under Colonial rule. However, the present context requires a significantly different approach in response to an increasingly globalised world. A language should not simply be viewed as belonging to an oppressor – but rather, should be utilised to benefit the country and its people. English is the dominant language of business around the world and the language that most international business is conducted in. A solid grasp of what has become the ‘lingua franca’ of global business and trade, is now an essential aspect of an internationally valued workforce. It is effectively the ‘link language’ of the world.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa reiterated in his speech to Parliament the necessity of developing the English language skills of the youth of Sri Lanka. This is undoubtedly a vital course of action to ensure that Sri Lanka can provide a competitive workforce for the future. A concerted effort to revitalise the English educational system in Sri Lanka will help break down barriers between different groups and provide them with professional opportunities as well paths to upward social/economic mobility. If implemented properly, the dividends of such measures will be felt for generations to come.

A summary of English education in Sri Lanka

Under the British, much of Ceylon’s educational system was predominantly anglocentric for Colonial benefit. The intention was to produce native local workers for the administration of the Empire. English education was initially carried out by missionaries to spread Christianity as well as the language. They intended to create an English speaking Christian upper-class.

The Colebrook-Cameron Commission (1833), transferred much of the educational authority from the Church to the local administrators. They wanted more natives in the civil service. A more uniform system of education was introduced – with English medium instruction. By the end of the 1830s, English schools had been established in Colombo, Galle and Kandy, based on the British model of education – as well as over 35 elementary schools.

This was not for altruistic reasons – such measures would reduce the cost and inconvenience of bringing in administrators from Britain. The locals would also be paid a substantially lower salary and the highest posts were reserved for the British. On the other hand, this provided a route for natives to pursue administrative jobs which were viewed as prestigious, and for a certain degree of upward social mobility that allowed them to go beyond caste.

The recommendations of the Executive Commission of Education in the 1940s paved the way for a turning point in the country’s education system. The initiatives implemented by Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara, the first Minister of Education of the State Council of Ceylon, introduced sweeping reforms in 1943 to transform the existing system. The changes were a major overhaul of the established educational structures and he introduced 54 central colleges around the country that could provide English education for free.

An initiative to provide free education from kindergarten to university level was implemented, leading to Kannangara being dubbed the ‘father of free education in Sri Lanka’. This concerted effort to promote fair access to educational opportunities beyond the elite classes led to a reduction in the disparity between different social groups. School enrolment and adult literacy rates drastically increased in the following years.

After Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, the country sought to rebuild its identity which had been crushed and stifled under the British. Pervasive anti-colonial sentiment and increasing friction between groups that had been stoked by Colonial ‘divide and conquer’ strategies finally culminated in the passing of the ‘Swabasha Panatha’ or ‘Sinhala Only Act’ in 1956. English was no longer to be the dominant language. After significant opposition by the Tamil minorities, the Act was reversed and provisions for the Tamil language were introduced in 1958. This paved the way for the two national languages, Sinhala and Tamil, to become dominant in all aspects of life in the country. English, on the other hand, experienced a decline in importance as nationalist sentiment led many Sri Lankans to abjure the language.

The opening of the economy and rapid globalisation has resulted in a substantial revival of interest in English education. Desperate parents are aware of the advantages that the language can grant their children and are willing to pay the exorbitant fees charged by the ever increasing numbers of international schools and private language schools.

What can be done?

As with most issues, there is no easy answer. Reacting to the growing necessity of English language proficiency, successive governments have attempted to meet the increasing demand. However, the results have proven to be severely lacking. The bilingual education system has yet to be adopted to a sufficient enough degree to prove its efficacy. Many schools tend to prevaricate and delay any substantial changes, citing difficulty in finding suitable teachers. Much of the existing methods of instruction focus on grammar and exams, whilst foregoing adequate training in soft skills and spoken English. Students will often pass their written exams yet remain extremely diffident when faced with the prospect of conversing at length.

Cognisant of these deficiencies, a program for ‘English as a Life Skill’ was introduced by the government in 2009. The intention was to address the persisting issues in the educational system and to promote practical skills in English and IT that would boost the employability of the younger generations. Whilst this program resulted in some progress, there remains much room for improvement and the new government must seize the opportunity to implement radical reforms to the educational system.

School administrators constantly complain of a lack of quality teachers and there is a significant rate of ‘brain drain’ with the most qualified and experienced professionals leaving the country for greener pastures abroad at an alarming rate. Subjects such as the social sciences, which require language skills and competence to be taught effectively, are often taught by teachers who do not have enough training or exposure – and will often revert to their first language due to a lack of confidence. Those that are qualified are often snapped up by the private institutions or will try their utmost to avoid being transferred to areas outside of the city. This is not at all to denigrate the private institutions, as they play an important role in providing education – but merely to point out that the overreliance on them is symptomatic of the deficiencies of the national systems. There is clearly a pressing need to address the loss of talent and to take drastic steps to incentivise qualified people to remain, and to attract people from abroad with qualifications and international exposure.

The following two examples (Vietnam and Singapore) of educational policies and language planning in Asian countries are highly pertinent to Sri Lanka:

Vietnam

The country of Vietnam is an interesting example. The nation comes from a French Colonial background and was ravaged by one of the most gruesome conflicts in contemporary history. The country has transformed exponentially in recent times and they have prioritised education to meet the demands of a fast growing economy and relatively young demographic. As part of this drive for education, the Education Minister Phung Xuan Nha has stated that 20% of the total state budget has been allocated to education (which is far higher than the global average).

Vietnamese students now have some of the best academic performances in Southeast Asia, even surpassing OECD countries such as the UK and USA. As part of the country’s pledge to focus on language learning, Vietnam has attracted over 437 foreign-funded investment projects relating to the education sector, registering a total capital of $ 4.3 billion. The comfortable expat life in Vietnam brings in large numbers of foreigners who teach at schools and language centres – although the government has begun cracking down on those teaching without appropriate qualifications. Of the more than 1,250 language and IT education centres in HCMC (as of January 2019), only 2% are foreign invested.

Furthermore, a strong push to prioritise English in higher education has led the government to direct universities to adopt a number of changes such as: offering English medium instruction, making English language a prerequisite for admission, establishing quotas for applicants with high language scores, offering scholarships for high English results and making English proficiency required for graduation.

Singapore

Singapore on the other hand, has had a relatively longer period of time to implement its language planning policies and is widely viewed as an educational success story. All subjects are taught in English medium from the start of schooling, except for a single subject in their mother tongue. As a multi-ethnic country with three major ethnic groups and over 20 identified languages spoken, English has proven itself to be a successful link language between the communities. The Constitution of Singapore recognises four official languages (Malay, Mandarin Chinese, Tamil and English) whilst symbolically naming Malay as the national language. In practice, English (including a colloquial version of ‘Singlish’) is regarded at the de facto language of Singapore.

After gaining independence, Singapore could have decided to reject the Colonial language of English and choose Malay or Chinese as the main language. However, they decided on pragmatic grounds that Singapore’s economic survival depended on English, whilst mother tongues would be taught as separate subjects to preserve tradition and ethnic identity.

Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew believed early exposure and home use to be vital for language acquisition. On early learning he stated that it was ‘crucial that a breakthrough must be made in the English language as early in life as possible’ – and on home use said ‘if [parents] want their children to do well…their children must also, besides Malay, speak English at home’.

When Singapore still had non-English mediums of instruction, and English was merely taught as a subject, it was identified that students were not reaching a high level of proficiency in the language. The government then required all subjects in maths and science to be taught in English medium.

Singapore is now one of the most proficient English speaking countries in the world at number 5 (as of 2019) and number 1 in Asia. Sri Lanka lags far behind ranked ‘very low’ at 78 in the global English Proficiency Index, trailing behind India (34) and China (40) which are described as ‘moderate’ level.

Singapore’s aggressive language policies and use of English as the language of law, administration and business, has allowed it to capitalise on growing economic opportunities in the region and integrate itself into the global economy as a hub of trade and commerce. Furthermore, its widespread use of English as a ‘working language’ has proven to be successful as a ‘link language’, bridging the gap between its different ethnic and religious groups.

Conclusion

There is clearly a pressing need to implement radical changes in the education system of Sri Lanka to address its pervasive deficiencies. It is most certainly a matter of urgency if we are to lay the groundwork for the coming generations and their professional aspirations. If Sri Lanka is to become a hub of investment and trade in the region, it is imperative that the population has the language skills to integrate into the global economy.

The benefits to social cohesion, by allowing English to fulfil its Constitutional place as a ‘link language’, will allow ethno-religious barriers to be broken down – thereby promoting stability.

This does not necessitate an erosion of tradition. As with the Singaporean example, it is possible to prioritise English education for pragmatic reasons, whilst giving one’s native tongue its due place to preserve culture.

(The writer holds an LLB (hons), LLM (Public International Law), and is a Barrister-at-Law (England and Wales), Postgraduate (PhD) Researcher in International Law at the University of Durham.)