Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 10 June 2020 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

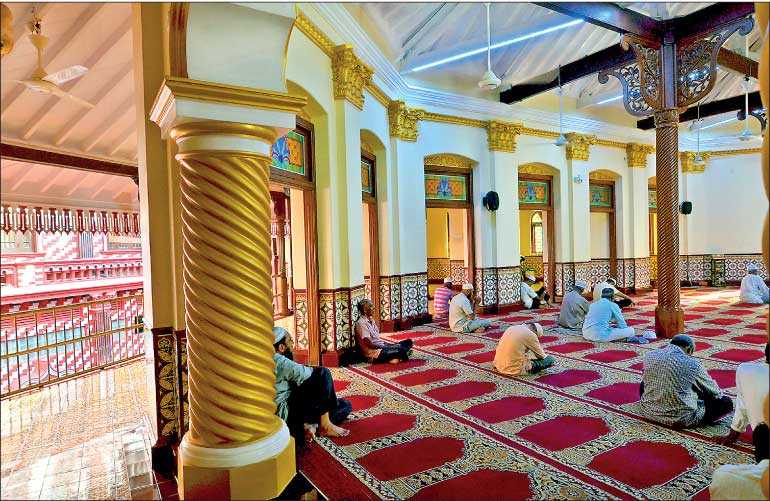

Burial of Muslim COVID-19 victims has become a political propaganda issue for the SLMC and ACMC. For the Muslim people however, it is simply the right of burial for their loved ones – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

“Learned institutions ought to be favourite objects with every free people. They throw that light over the public mind which is the best security against crafty and dangerous encroachments on the public liberty” – James Madison

The outcry for burial of Muslims who succumbed to COVID-19 had until recently been an exclusive matter of the Muslims, before being quietly echoed by the political leaders of other major parties. This cautious emergence of these political lions from their dens was triggered by their timely appreciation of the shifting political climate: elections are drawing near. It is thus difficult to ignore the political motivations of their spontaneous concern and criticism of the practice of cremating Muslims who die from COVID-19.

On 5 May, the Director General of Health Services, Dr. Anil Jasinghe confirmed a woman from Modara (aged 52) to have died from COVID-19 at IDH Angoda. As usual the national media suppressed the details of the dead, however social media revealed the name of the deceased as Fathima Rinoza, a Muslim by faith. Later that day she was cremated without even her husband being allowed to see her dead body. It is reported that the son of the deceased was forced by the hospital authorities to sign some papers consenting to cremation, whilst the rest of the family members were removed to Anuradhapura.

Just two days after the cremation of her corpse however, it transpired that she was not infected with COVID-19, nor was anyone in her family or those who lived in the same apartment. With the cremation of the misidentified COVID-19 victim, the Health Ministry spokespersons were quick to jabber on television that they would want to redo another test on her family members, without candidly deploring for their egregious mistake.

In Weligama, a Muslim woman was initially identified as being infected by COVID-19 but was later found not to be infected. She was subjected to further tests in the nearby town by the intervention of the Urban Council Chairman Rehan Jayawikrama, thus averting cremation under false pretext of COVID-19. As a ‘proper person’ he rightly exercised his power vested with him under QPDO on the disposal of the dead.

Other suspected victims weren’t as fortunate: Abdul Hameed Rifaideen (aged 64), was cremated on 6 May, suspected dead from COVID-19 without any concrete evidence to say so. None of the family members of the deceased were asymptomatic enough to degenerate professional ethics of one of the noblest professions in Sri Lanka.

Since then the health authority officials resorted to a series of gaffes relating to the testing process and the cremation of misidentified COVID-19 dead. The sobering reality of failures in the testing process was left to be exposed by some medical professionals, who also endorsed the right of burial demand of the Muslims.

Ravi Kumudesh, a technologist from Association of Government Medical Laboratory coincidentally admitted faulty COVID-19 positive results conducted by the following laboratories of: Colombo University, Jayewardenepura University, Kotelawala Defence University and the Ministry of Higher Education. He had poignantly asked why those samples had been sent to those laboratories for tests whilst the Ministry of Health had adequate resources, and opined that “it could be a sabotage and it should be investigated”.

Such claims raise doubts as to the accuracy of whether or not all those who died of COVID-19 were indeed tested positive by the Ministry of Health and/or by other laboratories, all of which are free standing and part of the government institutions.

Within this context, it is despicable that the Epidemiology Unit of Sri Lanka (EUSL), which produced The Provisional Clinical Practice Guidelines, is also unwittingly adding fuel to the fire to counter propaganda those who oppose the Muslims’ rights for burial. The EUSL built up its own Wikipedia page on COVID-19 in Sri Lanka which chronologically charts the development of COVID-19 related information. It publishes COVID-19 information very much in line with the government’s position on cremation, thus lacking its credibility as an independent professional institution, linking pro-government media information in support of the cremation option.

Perhaps worst of all, it highlights the arrest of a terror suspect of the Easter bomb blast in Dehiwala, glaringly unrelated to the COVID-19 scenario, in an attempt to link the arrests for those who had broken curfew law. Close inspection of how the information is dished out online poses a serious question relating to their credibility and ulterior motive.

When Muslims felt that they were being pushed to the wall, religious leaders like Rizvy Mufti played down his tone in a TV interview and ended up compromising with the burial of ashes of the cremated COVID-19 dead of the Muslims. Burying ashes of the dead, hitherto unknown and unacceptable to Muslim faith, became a moot point as Rizvy Mufti shifted the demand for burial to an argument of burying the ashes. Religious leaders never ventured to meet either the President or Prime Minister to put forward their demand for unknown reasons. In spite of this, Muslim political leaders stood firm in their demand for burial of the dead of COVID-19 victims.

Amid this wrangling, when the Catholic religious institutions were unusually reticent on the issue of cremation, a Catholic individual named Don Oshala Lakmal Anil Herath filed his Fundamental Right Application in the Supreme Court followed by his complaint to the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka on 7 May.

This seemed to be the wakeup call for the Muslims, triggering them to seek similar legal remedies from the highest courts of the country. Against this background former MP, Sumanthiran also offered to appear in a Fundamental Right Application on behalf of the Muslims on a pro-bono basis. On one hand, the burial issue became a matter of fundamental human rights of the Muslim people, and on the other, it had become a trump card for politicians.

Politically game changing decision for Muslims

At the end of the political wrangling, legal wrangling has taken its course. The irony is that the Muslim parties, who thrive on the innocent and voiceless Muslims, have several lawyers and even PCs (President’s Counsel) in their fold but none of them stepped forward to file any fundamental application on behalf of the community, when it desperately needed someone to fight for their religious rights.

The author recalls how the leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC), Rauf Hakeem, who enjoyed parliamentary privileges for over two decades at the expense of the Muslim population, jumped on the bandwagon of the lawyers team fighting for restoration of Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government in October 2018, had found no cue to go to the Supreme Court to intervene in the breach of fundamental rights of his own community.

Once Rishad Bathiudeen, the leader of the All Ceylon Muslim Congress (ACMC) filed its fundamental right application, challenging the only cremation option, the SLMC was prompted to file its own similar application with the Supreme Court. This demonstrates that burial of Muslim COVID-19 victims has become a political propaganda issue for the SLMC and ACMC. For the Muslim people however, it is simply the right of burial for their loved ones; ‘yaar kutrinaalum arisiyaanal sari’ (whoever is milling the rice grains, let it be rice – Tamil proverb).

COVID-19: Unique or ubiquitous

It is interesting to note that Sri Lanka has been working closely with WHO and its partner countries under its National Action Plan for Health Security of Sri Lanka 2019-2023, with a commitment to strengthening implementation of the International Health Regulations, but conveniently rode roughshod over the burial practice of WHO and its partners. Legal validity of removing the burial option, both in the PCPG (Provisional Clinical Practice Guidelines on COVID-19) and Quarantine and Protection of Diseases Ordinance amendment (QPDO), is not compatible with the dependence on factual sources and subject to legal challenge. Fundamental right applications seeking reversion of the option of burial in the QPDO, on the basis that the Minister of Health had acted ultra vires in amending the QPDO regulations, is the pivotal point of the argument pending hearings.

This is very much reflected in its PSPG developments and amendment to QPDO relating to the exclusion of burial options for Muslims. Besides these, the health officials amended the PCPG Version on 1 April, well before the Minister’s amendment to QPDO on 11 April. Nevertheless, the PCPG – 3 itself does not provide any power to the health officials to modify the regulations relating to restricting to cremation. Before any rules come into force there should be a judicial process to be adhered to by those who are vested with such power under any legislation; not only did the Health Minster issue her amendment by a gazette notification 10 days after the amended Version 4 of the PSPG, but the health officials overreached their boundaries by amending the PSPG. The overall events and narratives surrounding the exclusion of burial raise numerous questions:

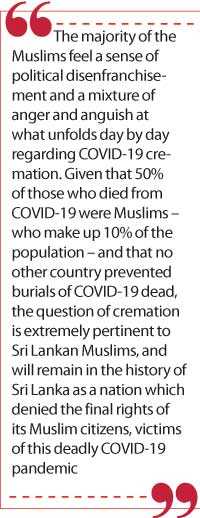

It is inevitably crossing the author’s mind as to how Muraleetharan, known by his nom de guerre Karuna (a former LTTE eastern Commander) was able to influence then Prime Minister, Mahinda Rajapaksa to revoke the extraordinary gazette notification (2162/50) issued by Minister of Public Administration, Home Affairs, Provincial Councils and Local Government Janaka Bandara Tennakoon, with regard to establishing a new urban council for Sainthamaruthu. Against this backdrop, the current President or Prime Minister, should exercise their power to invalidate the Extraordinary Gazette notification (2170/8) excluding burial, reconciling the political distance created between the Government and Muslims for the benefit of both. The majority of the Muslims feel a sense of political disenfranchisement and a mixture of anger and anguish at what unfolds day by day regarding COVID-19 cremation. Given that 50% of those who died from COVID-19 were Muslims – who make up 10% of the population – and that no other country prevented burials of COVID-19 dead, the question of cremation is extremely pertinent to Sri Lankan Muslims, and will remain in the history of Sri Lanka as a nation which denied the final rights of its Muslim citizens, victims of this deadly COVID-19 pandemic.