Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 25 August 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

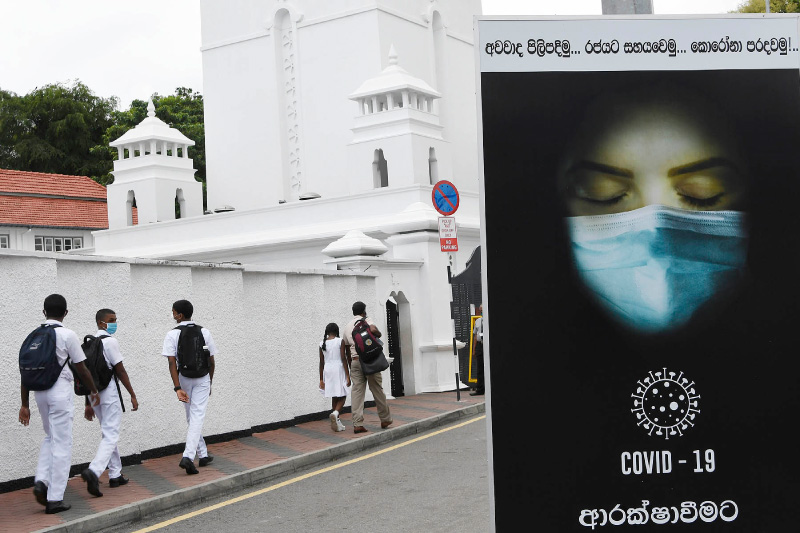

Education in this country is like a journey where we are all on this ship unhappily, but we cannot stop because there are children on board and each child had some destination. Now that the COVID storm has forcibly grounded the ship, let us look at this rickety vessel, or even better, look at the new ship which is supposedly in the dock getting ready for launch in year 2023 as a pilot – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Teachers are on strike. Even when teachers were not on strike, they were able to connect to only half of the student population. Now that they are on strike, all children are in total education lockdown. Of course children attending private school are continuing their distance education and the tuition masters are as active as ever, but the trickle of the public education tap dependent on teacher-student interactions is turned off.

Teachers are on strike. Even when teachers were not on strike, they were able to connect to only half of the student population. Now that they are on strike, all children are in total education lockdown. Of course children attending private school are continuing their distance education and the tuition masters are as active as ever, but the trickle of the public education tap dependent on teacher-student interactions is turned off.

What’s a parent to do? What should the teachers do? What should we all do? I suggest that we use this interregnum or ‘nonágathe’ to reflect on this thing called education.

Education in this country is like a journey where we are all on this ship unhappily, but we cannot stop because there are children on board and each child had some destination – i.e. the Grade Five Scholarship Examination (G5SE), General Certificate of education Ordinary Level (GCE O/L) or the General Certificate of Education Advanced Level (GCE A/L) – that they need to reach on time.

Over the years, these examinations have become dinosaurs, but parents are too invested in the system to question them – my child is 16 or whatever, I have found ways and means to survive the system, repairs can wait, would be their attitude, naturally.

Now that the COVID storm has forcibly grounded the ship, let us look at this rickety vessel, or even better, look at the new ship which is supposedly in the dock getting ready for launch in year 2023 as a pilot. The dockyard is the Ministry of Education Reforms, and the chief engineer is Dr. Upali Sedere, the Secretary to Ministry and architect of the chapter on education in the 2019 Gotabaya Manifesto. Incidentally, that chapter is one of the best I have seen on education in a manifesto.

From the look of it, it could be a fine ship. For example, the pedagogical vision behind the curriculum reforms is:

“Transforming from WHAT to Learn to HOW to Learn; Facilitate constructive learning and deep learning than rote learning; [Inculcate] a spirit of inquiry in students; Promote self-directed learning than directed instruction; Move toward more real-world contexts in learning; Inculcate the spirit of lifelong learning; Shift from examinations to assessment & evaluation [MoE, 2020 Nov].”

Grand ideas since 1997

This is not the first time such grand ideas were put forward.

In 1992, the newly-formed National Education Commission published a report where the output of education was conceived as youth with five basic competencies – i.e. Communication; Personality Development; Competencies related to Biological, Physical, and Social Environment; Ethics and Religion; and Leisure and Play; and Learning to Learn – that will lead to the eight national goals of education. To date, these competencies are repeated in textbook and teacher guides, but largely ignored.

The Presidential Taskforce of 1997, formed during President Chandrika Kumaratunga’s time, published a report outlining a plan for implementing the recommendations of the National Education Commission. A summary of its approach is as follows:

“There are strong arguments for a major shift in Education goals and practices and a comprehensive and coordinated approach to change. The principal elements of this shift are: (1) Self-realisation; (2) Life-long learning with emphasis on learning to learn; (3) Inculcating humanistic values and (4) Stimulating a balanced mental and physical growth of the individual (PTF, 1997).”

The overlap between pedagogical objectives of the 1997 document and the 2002 one is remarkable. An exception is the all-important reform of examinations emphasised in the 2020 version.

Why did not these grand ideas of 1997 take root? Why are we still talking the talk? What happened between 1997 and 2021? Will these grand ideas work this time? If I must pick one key factor for success, I will pick the national examination system.

National Examination system as the obstacle

National Examination system as the obstacle

Education is not an island. Any education system is a part and parcel of the socio-cultural landscape of a country. Even if one were to clear the jungle and cultivate here and there, if not tended day and night, the jungle will grow back over the clearing. This is perhaps what happened to the Kannangara Central Schools. Envisioned as elite schools at the rate of two per district giving opportunities for the best of the best, they were diluted by politicians putting name-board on schools without the resources to match. Yes, politics can rout out any well-thought-out plan.

The next relevant law of nature is ‘those who have shall receive more’. The set of so-called popular schools is the manifestation of this ‘law’. For example, in the absence of a genuine effort by succeeding governments to provide equal opportunities, schools with better endowed parents have strived on their own to improve own schools. These schools then attract more students because they are endowed better thanks to these parents. What we have today is self-propagating set of 100 or so schools which have become magnets for parent from across the country aspiring for schools with better facilities and better social networks. Class sizes inevitably are over 50 in these schools, but who cares.

These popular schools are Government schools in name only. Government pays for teacher salaries and nominal amounts for upkeep. Tens, hundred or thousand times more is spent by school development societies. Royal College reportedly with an annual budget of 100-200 million is a case in point.

Each succeeding government has managed to conceal this façade of a free education by maintaining an examination system which gives the whole thing the cover of a merit-based system. If you do well in G5SE you get to go to one of these popular schools. The fact that these schools are already filled to 90% capacity with children whose parents maintain these schools, is another matter. The GCE O/L is another entry point and the GCE A/L is the other.

Grade Five Scholarship Examination (G5SE)

A major output of the reforms initiated in 1997 was a revamped primary curriculum, but today, primary education is a disaster. Children and parents are weighed down by content from an invisible curriculum which is essentially the past papers of G5SEs past. A close look at these examination papers reveals an examination that contradicts norms of primary curriculum, or the equity and effectiveness one would expect from a national examination.

Many have even noted that this G5SE examinations is really a form of child abuse, but nobody seems to want to rock the boat. Under pressure to show results for this examination, teachers resort to coaching children for the exam using study packs consisting of 20 or more years of past papers with answers, and children are learning little parrots.

I have had first-hand experience of this phenomenon from leading an action research on repurposing existing primary curriculum to develop the whole child in the Ampara education zone. The work spanning the two years from 2012-2014 was done at the request of Wimalaweera Dissanayake, then Minister for Education in the Eastern Province. Teachers were happy to change their teaching and learning but there was pressure from parents for whom the GS5E was the only way for uplifting their children and through them the family.

Now that no exams are on the distant horizon

The biggest relief afforded by the pandemic is the inability of the centre to conduct national examinations on schedule. This is a blessing in disguise in my opinion. As I said before, the centre has managed carry on a façade of free education thanks to the national examination system.

There are many anecdotes about the money parents spend for success at these examinations. One is about a family which received 10,000 per month for nutrition from a donor but all that money has been used in GCE A/L targeted tuition for the child. The donors learned of this only when they found out that the child was suffering from malnutrition. As for research, a 2018 NIE study published in their Sandharbha newsletter has shown that 72% of students do not attend second term in Year 13. Presumably these students rely on tuition masters to prep them for the exam.

True, the delaying of exams jeopardises education plans of many students, especially those who aspire for free of charge education in a public university. But, in the big picture, this group constitute less than 10% of the youth cohort in the country. Fooled by the pretence of equity in our education system, we totally ignore the plight of 90% of youth turning 18 every year and continue to provide a free of charge university education to less than 10%.

We should use the present no-exams interregnum to question our education system and come up with alternatives without waiting for promises which may or may not materialise.

Some ideas for a different kind of education

If you are a parent reading this and your child’s teachers are on strike, consider yourselves the lucky ones. Distance education has been reduced to online education without a consideration of offline one-one or small group options. Students, parents, and teachers are exhausted or at the point of exhaustion, but they are unable to get out of the treadmill. Why not try the following or your version while there is breather?

1. Give you a child a complete break from conventional studying. If she was on ‘online’ education, give the internet a break.

2. Find a quiet place for the child.

3. Find a mentor for the child. Could be an older cousin or a family friend who is contactable over the phone.

4. Find an unused or partly used notebook for a notebook and let her name it (say, ‘My Lockdown Diary’)

5. Tell her she is responsible her own learning and ask her to name something to do in each of the following areas, for example: (i) Academic (ii) Physical (iii) Aesthetic (iv) Creative (v) Social (vi) Spiritual, and (vii) Responsibilities and Relaxation

6. Ask her to reflect on what she has done in the past, what additional things she would want to do in each, and then draw up her own weekly timetable. The child should take ownership of her education.

7. In academic work, ask her to pick two to three topics per week from any textbook in any subject. If she has difficulties, find somebody who can help her. It could be a tuition master.

8. Social activities can be things one does as a family or regular chats over the phone with friends. Do not hesitate to let the child call her teachers. She/he may be on strike, but teachers always go beyond the call of duty to listen to a child.

9. Suggest that she documents her experiences as a diary or in visual media or a medium which she chooses.

10. If she or he does not want to do anything specific for activities (i) to (vi), don’t worry. If parents provide a structured environment for household responsibilities while allowing time for fun and relaxation, those activities give ample learning opportunities.

Don’t wait for a dysfunctional central ministry to find solutions. Practice what you can during this time, and when teachers return, empower them to do what is best for children and not blindly follow directives from the centre. Use your experience, to speak up from freedom from this insensitive, and outdated monolith of an education system.

(The writer, Ph.D. MPA, is the co-coordinator of www.educationforum.lk)