Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 16 June 2022 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Biogas collection unit at Pattiyapola

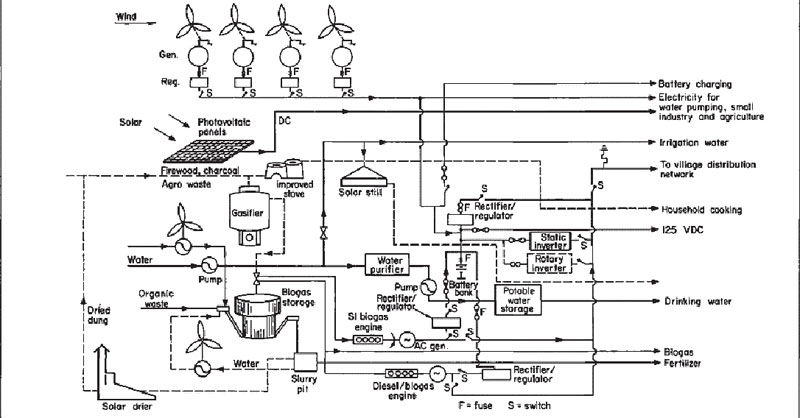

Rural Energy Village – full scheme

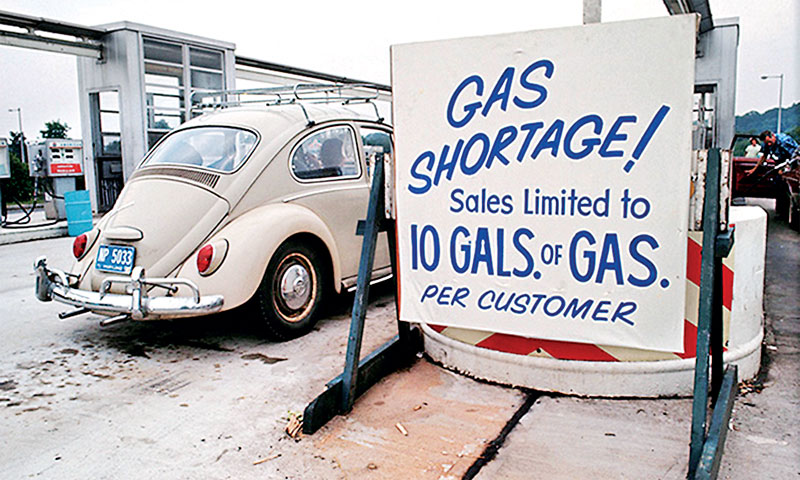

US in 1973

Service station with biogas as fuel

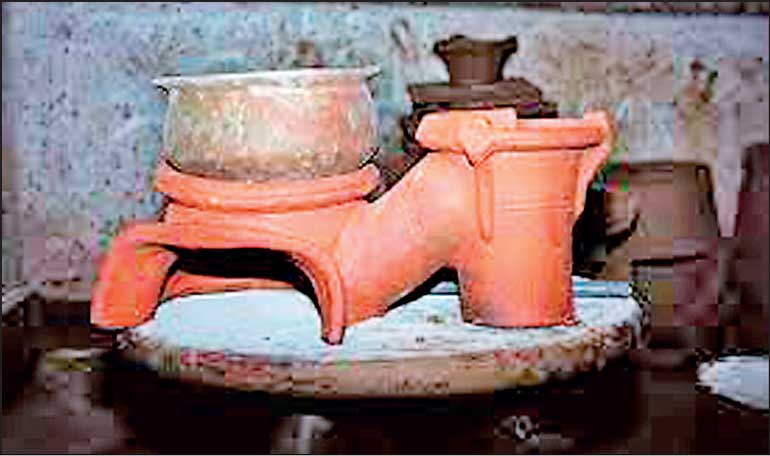

Anagi Uduna – fuel-efficient cookstove

1973 was the year when the world awoke to the fact that energy can be costly and thereby scarce as well – the year of the first global energy crisis! The crisis was a novel experience too as the world was getting quite used to cheap fossil energy – primarily oil – and was becoming quite proficient – again definitely not efficient – in use.

1973 was the year when the world awoke to the fact that energy can be costly and thereby scarce as well – the year of the first global energy crisis! The crisis was a novel experience too as the world was getting quite used to cheap fossil energy – primarily oil – and was becoming quite proficient – again definitely not efficient – in use.

When a few countries who were the primary oil-producing countries got together and started fixing prices at a high value while controlling the output in addition to placing embargos, all the economies were immediately affected. An interesting result in Sri Lanka was the decision taken to stop all public offices working on Saturday mornings. The five-and-a-half-day working week practice effectively came to a five-day working period. The idea had been the energy saved and cutting costs were more critical than the work achieved.

We see the same line of thinking today with holidays being declared in double quick time and as I write Friday has become a non-working day for us. As a country with a world record of public holidays, we must be conscious of these decisions as we have to have a much more concrete and productive strategy to overcome the current situation. Some accumulated savings are not going to help. The 2022 scenario is local and hence the challenge of overcoming has to be through our efforts.

In 1973 the cost of a barrel of oil to us was $ 4 with the expenditure coming to Rs. 274 million. In 1973, Sri Lanka witnessed a gathering in Colombo that came together to have the Colombo Declaration in pushing the biogas technology to serve the masses who are facing an energy crisis. UNEP also initiated the concept of a renewable energy village on every continent and the first village materialised in our country. Pattiyapola down south became the location for this village where the showcase element was the biogas plant.

Both thermal energies for cooking and electricity were given to more than 40 households. Additional energy systems like solar and wind were present too and the village offered a picturesque location to any visitor. I have to admit that as a chemical engineering undergraduate visit to Pattiyapola in 1982, also shaped my future as I got hooked up on renewable energy in general and biogas in particular. Considering that this village became a one of its kind in the world we failed collectively to benefit from this pioneering venture.

Another development at the same time was the biomass cook stove – Anagi Uduna – resulting from the effort of many institutes both public and private. Anagi materialised as an answer to a solution to the gross use of biomass in cooking and there was a dire need to reduce the consumption of fire wood as the cook stove then used at home was quite inefficient – 3 stone hearth. Anagi demonstrated fuel efficiency, environmental performance, and overall productivity in cooking and I still view this as an important collaborative development as a solution to a problem.

CEB was active and leading in both these developments at the time. It is quite hard to visualise the current CEB taking that role! The renewable energy village at Pattiyapola did not survive for a long time with most of the items ending up at local scrap sites. Our attempts to secure some systems for the University of Moratuwa failed as the method of disposal had been through tendering. What a head start we would have had if we have understood the importance of this venture in terms of the emerging role for renewable energy systems, technology development and skills and knowledge.

The intention was to showcase Pattiyapola to the world, but how many of us in Sri Lanka today are aware of this. This habit of Sri Lanka only responding to project implementation and as soon as the funds dry out, planning to move to the next project has never done us much good. I have traced a few individuals overseas who claim that their life’s being changed due to their involvement with this UNEP project in Sri Lanka. Serious misunderstanding over energy use and availability by our decision-makers made this a lost opportunity for Sri Lanka. One could also indicate the closure of micro-hydro sites for tea industries to pave the way for grid connection. Japan which was placed in a similarly precarious situation, however, responded differently and went on to become a highly energy-efficient nation with production tuned to efficiency.

If we had continued to invest and adopt anaerobic digestion – i.e. biogas technology – we really should have been in a different place today. Our penchant to embrace projects rather than think, assimilate and act has driven us down in almost all sectors. We have worked hard to receive what someone else conceptualises and push down our planning cycles and in many situations, they have not helped the country to move ahead. Imagine the closure of the ammonia/urea facility at Sapugaskanda, which was built with $ 250 million and with local technical management. A plant that gave Sri Lanka urea fertiliser and also electricity to the grid was closed because of price mismatches.

I remember listening to a high-level minister in England while being a postgraduate student there, the intention to close the facility over a pricing issue. Though the subject matter directly came within my professional area there was no chance of a discussion. If we had the ammonia and the urea plant present at this stage one can imagine whether we will have this crisis ever. What the silent majority does not realise is that the technical reasoning hides very much the real interests and again some of the technical aspects are much more made up than real too. When facing an issue one must exercise creativity to find answers and this too was a recipe indicated when COVID-19 started sweeping economies. When the national innovation eco-system is dynamic and well-connected, better answers emerge. With LPG availability causing such misery to many, a community roadmap to enable biogas is almost a must. Media instead of continuing to showcase misery must accelerate promoting solutions. As we continue to engage with political biases the masses never see opportunities and society only regresses.

When Japan had the Fukushima Daiichi disaster and went on to shut down more than 40 nuclear reactors they moved on quickly with biomass pellet power – in fact creating global supply chains to Japan – as well as developing cars powering homes taking up some critical loads. Japan has shown a 3,000% increase in biomass pellet consumption since 2017 and this is pretty amazing.

The leadership decided on the ‘best energy mix’ and the technical process was on. They demonstrated fluidity in managing the developing situation and the success of course was that they had technological resilience. We should be looking at Norochcholai being converted to biomass power. The University of Moratuwa has shown the immediate possibilities of this. The US has shown coal plant conversions to biomass. We constantly engage in political dialogue sans technology when technical solutions are the most rational solutions available. Hope that Sri Lanka wakes up from this scientific illiteracy slumber quickly.

In innovation advice to the leadership is while promoting innovation – which is a must-have for a company – there is also the condition that an experiment should not destroy the company. Unfortunately, today we are a victim of a grand-scale experiment that destroyed multiple sectors and resulted in significant economic backsliding. Again in recovery, there is a clear need for a roadmap with defined mileposts in recovering from this situation and realising in a season or two the normalcy. Of course, the way back is different and difficult from the way down and the costs are going to be significant and I am sure multiple publications are going to come taking Sri Lanka as the case study. However, we should now make use of this situation to come out better and stronger.

Our collective failure to invest in technology to support growth and ensure resiliency has pushed us into the present situation. How many would still acknowledge this fact and set the agenda differently for tomorrow? Seeing the behaviour at this darkest hour, it is apparent that such an admission is not forthcoming. We are still trying to borrow our way out through mortgaging continuously the future. The level of national poverty has the potential to impact everyone and including the newborn.

Imagine that as a country for over four decades instead of having clear empowerment programs we institutionalise programs such as Samurdhi. What we should have is a clear date and time when the last Samurdhi recipient would be in the country. Instead, we are still celebrating adding more to the scheme. Handouts are never the way to support growth and this is a fact both internally for a community as well as externally for a country. In 2021 there were 1.5 million households registered to receive Samurdhi. The census records up to 200,000 households in the country as ‘poor’ and therein begs the question of why this disparity in numbers.

While the nation in the ICU may require a specific immediate treatment, the immediate medium-term demands a strategy that understands food, energy, and a technological resilient roadmap. Again for ease of communication and to ensure understanding and to develop trust, specific actions needs to be identified and internalised.