Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 6 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This article is based on the Keynote Address delivered by Prof. Colombage at a recent conference jointly organised by the Sri Lanka Forum of University Economists and the Department of Social Studies, Open University of Sri Lanka

This article is based on the Keynote Address delivered by Prof. Colombage at a recent conference jointly organised by the Sri Lanka Forum of University Economists and the Department of Social Studies, Open University of Sri Lanka

The ultimate goal of socioeconomic development is to improve people’s quality of life dependent on access to basic needs such as food, safe-drinking water, shelter, clothing, education and health care. An important factor that determines these dimensions of quality of life is income, usually measured in terms of per capita income which is equivalent to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) divided by population. Money is not everything, but one could also argue that money is needed to buy everything to fill the basket of basic needs listed above. Hence, GDP growth is an essential ingredient for socio economic development.

Politicians use their power to interfere in almost all areas relating to socioeconomic development, and navigate the country either to economic prosperity or to disaster. That is how the political economy comes to the picture. Politics is about elections, and elections are about the economy. The economic benefits to be given to masses take top priority in almost every election manifesto, the only exception might be the last presidential and general elections which were decorated with the slogan of ‘good governance’ by the then opposition, now in power.

In order to satisfy the voters so as to retain power at the next election, politicians have a tendency to give hand-outs like cash transfers to households, food subsidies and various other welfare benefits through populist policies. Another mechanism commonly used to attract the voters is to create public sector employment for them. These kinds of preferences invariably lead to raise Government expenditure, budget deficit, public debt and money supply. The outcomes are high cost of living, subsidy cuts and various other hardships which prompt the voters to change the regime through periodic elections. This is the vicious politico-economic cycle that we have experienced over so many decades.

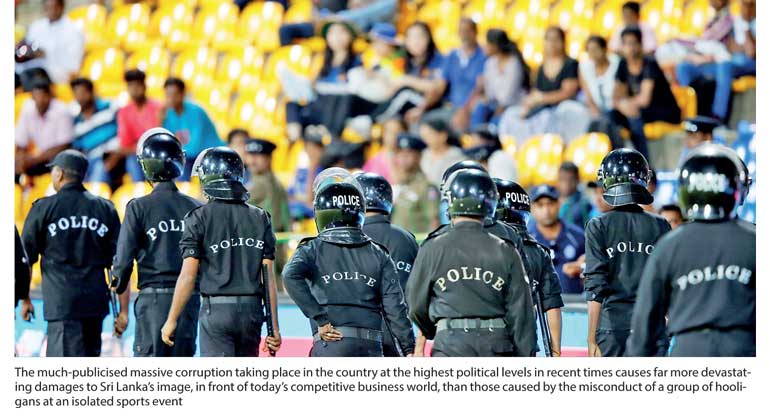

Recently, I came across a timely newspaper article written by Dr. Indrajit Coomaraswamy, Governor of the Central Bank and champion sportsman, condemning the unruly behaviour of a group of local spectators who reflected their anger against our own cricket team for their humiliating defeat at a cricket match with India. I totally agree with him in condemning such unbecoming conduct of those spectators. Undoubtedly, such behaviour has adverse effects on the country’s international image, as rightly pointed out by the Governor.

Moving from the cricketing world to economic realities, I would like to stress here that the plight of our economy is no different from that of our beloved cricket team. The root cause of the problem of the downfall of the cricket team is political interference, according to some sports analysts. Although I do not have sufficient information to subscribe to that argument, I am able to contend that political interference is the root cause of the multiple socioeconomic problems that have ravaged our motherland since Independence. The short-sighted policies implemented decade after decade under the guidance of the political masters with elections in their minds have driven the country to a very gloomy destiny by now, as I will highlight in this article.

Just like our fielders who missed so many catches in recent cricket matches paving the way to their successive defeats, our policymakers too missed many opportunities that could have been exploited to uplift the country from the economic mess. The two turning points that stand out among such ‘catches’ are, (a) liberalising the economy by the UNP Government in 1977, and (b) ending the 30-year war by the SLFP-led Government in 2009. So, credit should go to both political parties. Both turning points brought widespread economic benefits to the country and boosted investor expectations. Unfortunately, the growth momentum got diluted in no time after those landmark events owing to various reasons, mostly dominated by political interests.

In my opinion, the much-publicised massive corruption taking place in the country at the highest political levels in recent times causes far more devastating damages to Sri Lanka’s image, in front of today’s competitive business world, than those caused by the misconduct of a group of hooligans at an isolated sports event.

The country’s economic growth is constrained by severe imbalances which can be simplified by the ‘two-gap  theory’. First, there is the domestic savings gap resulting from low savings in the private sector and dis-savings in the Government budget. Second, the excess of imports over exports causes the foreign savings gap. These two gaps compel the country to borrow indefinitely from domestic and foreign sources, and getting caught in a debt trap.

theory’. First, there is the domestic savings gap resulting from low savings in the private sector and dis-savings in the Government budget. Second, the excess of imports over exports causes the foreign savings gap. These two gaps compel the country to borrow indefinitely from domestic and foreign sources, and getting caught in a debt trap.

Borrowings from domestic market sources to finance the budget deficit pre-empt resources from the private sector, and raise market interest rates. If these borrowings are mobilised from the banking sector the money supply will rise causing high inflation. Politicians seem to prefer such ‘inflation taxation’ that mostly affects the poor, rather than taxing the affluent with rigorous enforcement.

The resource imbalances have led to misalign the macroeconomic fundamentals. But no effort seems to have been taken so far to rectify these fundamentals.

The trade-off between welfare and growth has haunted the annual budgetary preparation exercises of the successive governments since Independence. Populist policies have taken a prime place in budget proposals for political survival of the ruling political party, thus undermining the market reforms that are needed to correct the disarrayed macroeconomic fundamentals so as to facilitate economic growth.

In 2016, the budget deficit was 5.4% of GDP reflecting an excess of Government expenditure (19.7 of GDP) over revenue (14.3% of GDP). This year’s budget deficit too is going to be well above 5 percent of GDP. The accumulated foreign debt which amounts to nearly $ 50 billion is a disturbing concern, given the stagnant export earnings.

The expansion of public sector employment by all regimes to the tune of 1.5 million employees has led to absorb as much as 33% of total Government expenditure for salaries annually. Welfare transfers to households including Samurdhi payments, food subsidies and other benefits accrue 18% of Government expenditure. Interest payments account for 35% of total expenditure. Escalation of foreign borrowings to fund the huge infrastructure projects undertook by the previous regime has caused rapid accumulation of foreign debt with high interest rate commitments, and a corresponding increase in debt service payments, though some of those projects are essential for the country’s progress.

In spite of the election pledges given by the ruling party to the Federation of University Teachers’ Association (FUTA) to allocate 6% of GDP for education, the actual allocation (for both school and higher education) was only 2% of GDP last year, and the same ratio remains this year as well, according to the budget estimates.

The total tax revenue which amounts to only 12% of GDP is mainly generated from indirect taxes imposed for goods and services consumed by the masses, and hence, they have to bear the bulk of the tax burden. The indirect to direct tax ratio is 80:20, and the new Inland Revenue Act is claimed to mobilise more income taxes so as to change this ratio in favour of low-income earners. The outcome of this reform is yet to be seen.

Politicians display an inflation-bias in formulating policies, as they prefer to please the electorate by offering various hand-outs at the expense of price stability, as discussed earlier. It is the prime responsibility of the Central Bank to insulate the economy from such political pressures and to ensure price stability. This is why so much attention has been given worldwide for central bank independence.

Although price stability is a prime objective of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, the leeway available to conduct its monetary policy towards that end is extremely limited, as the bank has to wear several hats at the same time. Apart from the conduct of monetary policy, the Central Bank has to act as the fiscal agent and the manager of the public debt, and also as the manager of the provident fund. At the same time, the foreign reserves of the country come under the purview of the bank.

Currently, the inflationary pressures are building up as reflected in the year-on-year rise in the consumer price index by 6.0% in August 2017, as against 4.4% a year ago. This calls for tightening of the money supply growth which is currently running at high of 23% on annual basis, compared with 17% a year ago. However, the Central Bank has not raised its policy rates since the marginal upward revision effected last March. A reason for this would be the bank’s concern about the possible adverse effects of a rate hike on Government borrowings.

Thus, the objectives and functions of the Central Bank are conflicting most of the time, and the bank is bound to follow the directives of the Government when disputes arise, as per Monetary Law Act. Specifically, the bank’s independence has been severely restricted by its obligation to accommodate Government borrowing requirements. This is reflected in the amounts of six-month advances given by the bank to the Government which always exceed the statutory limit of 10% of Government revenue.

The Treasury bond scam poses many questions on the independence and the credibility of the Central Bank in recent times. Further, shifting the subject of central banking and monetary policy from the Ministry of Finance to the Ministry of Policy Planning and Economic Affairs headed by the Prime Minister in September 2015 could be interpreted as an attempt to belittle the limited independence that the Central Bank had enjoyed previously. The bank is required to consult the Ministry in formulating monetary policy according to this arrangement. Thus, the Central Bank seems to have lost its autonomy with regard to monetary policy matters altogether leaving no hope for inflation targeting, as envisaged in its monetary policy framework.

According to the official projections, the annual GDP growth rate is expected to remain flat at 5% during 2018-2021. This is somewhat disappointing, as it is lower than the annual average growth rate of 5.1% maintained during 1977-2016. This reflects economic stagnation. Currently, the country is unable to move forward with its obsolete ‘factor-driven’ growth model which had lifted growth rates to a higher trajectory from the late 1970s up to mid-1990s by mainly utilising cheap labour inputs and foreign direct investment (FDI) for garment factories. As the next step, the ‘technology-driven’ growth backed by knowledge-based economy is not forthcoming due to the policy misalignments that I elaborated in this article. FDI inflows to Sri Lanka remain less than 1% of GDP, in comparison with 6% of GDP in Vietnam and 4% of GDP in Malaysia.

The annual rate of inflation is projected to be at 5% during the next four years without reflecting any deceleration. This calls for further depreciation of the rupee, and the implicit exchange rate derived from the official projections indicates an annual depreciation of around 2% in the next four years with a resultant fall in the value of the rupee to around Rs. 180 a dollar by 2021.

The present Government’s economic agenda is not clear though the PM has presented several economic policy statements to the Parliament from time to time. The next one is scheduled to be presented this week. There does not seem to be any firm political commitment towards resource balancing or market reforms in any of these statements.

The Government’s flagship project Megapolis, which originally envisaged FDI inflows to the tune of $ 45 billion during five to 10 years, does not seem to take off so far in the context of extremely low levels of FDI inflows.

Meanwhile, the Economic and Technical Cooperation Agreement (ETCA) to be signed with India is unlikely to be of any help to overcome the current economic problems. Such agreements with numerous countries will get very complicated over time, and they will eventually become “spaghetti bowls”, as articulated by the renowned trade economist Prof. Jagdish Bhagwati of Columbia University. It is miraculous to expect any trade expansion through preferential agreements without putting the house in order as elaborated in this article.

Putting the house in order is nothing but correcting the macroeconomic fundamentals and executing the market reforms. Strong political commitment is needed for the success of these adjustments.

(Prof. Colombage, Emeritus Professor, Open University of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])