Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 25 December 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is estimated that there are some 6,000 wild elephants in Sri Lanka today. This then means that there is a treasure worth more than Rs. 23.4 billion ($ 128 m) out in the wild

“There is no creature among all the beasts of the world which hath so great and ample demonstration of the power and wisdom of almighty God as the Elephant” – Edward Topsell

From time immemorial, travellers of days gone by and modern-day tourists have been fascinated by Sri Lanka’s elephants. Today, wildlife, and elephants in particular, is a major component of Sri Lanka tourism’s product portfolio.

From time immemorial, travellers of days gone by and modern-day tourists have been fascinated by Sri Lanka’s elephants. Today, wildlife, and elephants in particular, is a major component of Sri Lanka tourism’s product portfolio.

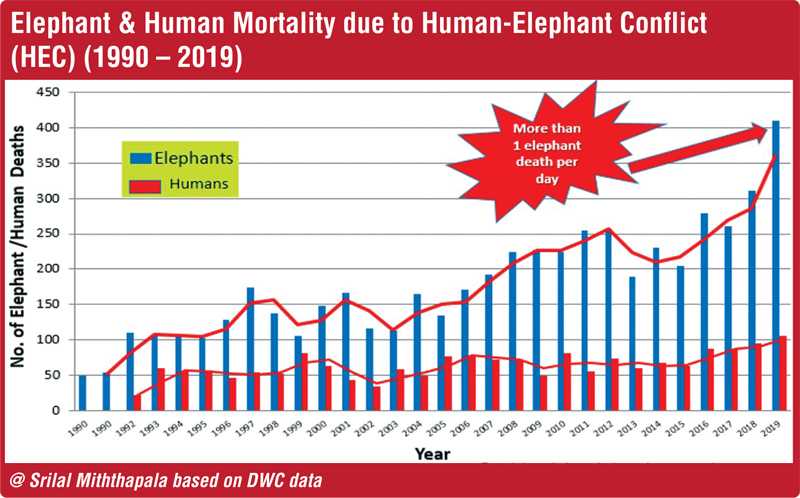

Unfortunately at the same time, due to haphazard and unplanned development, encroaching into hitherto elephant habitats, there are widespread altercations between man and elephant, resulting in large numbers of elephants dying. Today Sri Lanka has earned the dubious ‘honour’ of being rated as the country with the highest number of elephant deaths in the world.

In this analysis I attempt to evaluate the economic benefits of an elephant for tourism, using some reasonable and research based assumptions, which may open the eyes of the administrators to holistically and seriously look into this major issue.

The elephant in Sri Lanka and tourism

The world’s largest living land animal’s sheer majesty, size, and calm but latently powerful demeanour, is awe-inspiring. Elephants have always fascinated visitors to Sri Lanka, which boasts of one of the largest populations of wild elephants in Asia.

The ‘Gathering’ of Elephants every year on the banks of the Minneriya-Kaudulla reservoirs is now world famous. Just 3.5 hours’ drive from the city of Colombo one is assured of sighting wild elephants at the Uda Walawe National Park (UWNP) all year round. So elephants and tourism are closely linked. In fact the number of tourists visiting national parks in Sri Lanka has risen from 20% of all tourists visiting the country in 2015, to 47% in 2018.

|

|

The Human-Elephant Conflict

Due to unplanned development, encroachment into national park buffer zones over the years, and with no cohesive mitigation plan in place, the human elephant conflict has now reached serious proportions. Deaths of wild elephants at the hands of villagers has been steadily increasing, and last year it topped 400. This means that a wild elephant dies every day. At the same time some 80-90 humans also lose their lives due altercations with wild elephants.

This is indeed a very grim and sad situation, which has led Sri Lanka recently to earn the dubious ‘honour’ of being rated as country with the highest number of elephant deaths in the world. While this indeed disastrous to Sri Lanka as a country , to keep losing one if its greatest and most charismatic species, will have a slow, but long term effect on tourism.

So for a moment I thought I would put aside my ‘environmental and wild life’ cap, and study this problem from an economic angle (actually this idea was suggested to me by my friend Sanath Ukwatte, the President of the Tourist Hotels Association of Sri Lanka).

Calculation of economic value of elephants in Sri Lanka for tourism

Results

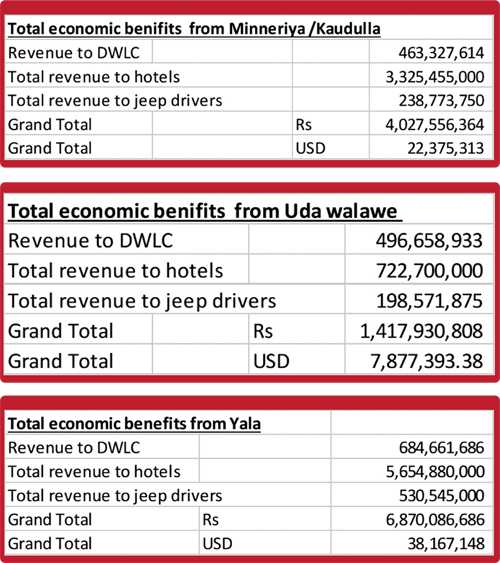

From the analysis it is seen that the overall economic value of a single wild elephant to Sri Lanka tourism is close to Rs. 4 million or $ 21,400.

The highest value, as one would expect, is in Minneriya-Kaudulla, area (Rs. 10 m per elephant) where the world-famous ‘The Gathering’ attracts a large number of visitors, while the abundance of elephants is also large.

Yala accounts for a value of Rs. 1.7 m, since elephant abundance is relatively low there.

The lowest is in UWNP at Rs. 1.6 m per elephant, which is mainly because UWNP has a larger population of elephants, in a relatively small park.

Conclusion

It is estimated that there are some 6,000 wild elephants in Sri Lanka today. This then means that there is a treasure worth more than Rs. 23.4 billion ($ 128 m) out in the wild.

This value of a single elephant taken in a different context, shows that if we lost some 407 elephants in 2019, the value of our loss is about Rs .1.6 b ($ 8.8 m).

Certainly this study may have some shortcomings. However all assumptions made are on the conservative side and errors, if any, will only give results which are less than the actual.

The important fact is that from this study we can at least begin to understand the full potential of this national treasure we have.

It may be already too late to turn the tide, and save this magnificent gentle giant from total annihilation unless urgent and cohesive action is taken by the Government.

References: