Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 16 September 2017 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

I once came into contact with a woman on account of a professional relationship we had. We had met to discuss her prolonged absence from work. With a reserved demeanour and a soft voice, she claimed that she had to run her father’s shop back home as he had not been well and hence she said that she had not been able toleave home.

After the third conversation that I had with her, she explained the actual reason for her absence. She had been pregnant and her boyfriend’s mother had taken her to a ‘doctor’ so that she could have an abortion. She said she had suffered from bleeding for some time, that she was unwell for a long time thereafter and had lost interest in life. According to her, her parents had no idea about what she had gone through.

Sara, a domestic worker, mentioned in passing to me that she thought taking the pill was the reason for her excess weight. We got talking and she eventually told me how she was introduced to the pill. When she conceived for the second time, she went to a clinic and underwent an abortion as she thought would not be able to afford to care for another child and that she would have to stop working if she had that child. Her husband works as a nattami. Sara is a Catholic. After the abortion, she went to the nearest Catholic Church to confess her ‘sin’. The priest spoke with her, directed her to the Family Planning Association and since then she has been using the pill as contraception.

The above are anonymised real life accounts of two women who have undergone abortion in a country where the law prohibits it except where the life of the mother is in danger. The statement by the Catholic Bishops Conference condemning the Government’s decision to legalise abortion under specified conditions has revived the debates and conversations regarding abortion, its ethics and the role of the state in its regulation.

According to news reports on 3 of September the Government has decided to withdraw its proposals for reform due to religious and cultural reasons. Be that as it may, the issues that have been debated on raise several questions that require serious reflection.

In this article I offer some reflections based on which I take the following position in this debate. I hope that by sharing these reflections I will draw attention to a wider range of concerns that should be taken into account in determining the way forward.

Prevailing law

Abortion has been criminalised in Sri Lanka since 1883. Under sections 303 to 306 of Sri Lanka’s Penal Code, voluntarily causing miscarriage is a crime punishable with up to three years of imprisonment. If the woman dies due to an act carried out with the intention to cause a miscarriage the punishment is up to 20 years. If such miscarriage is caused without the consent of the women the punishment is up to 20 years of imprisonment. The only exception to these criminal offences is where the miscarriage is ‘caused in good faith for the purpose of saving the life of the woman.’

Not much is known about the level of awareness among the public regarding these laws. In a study carried out 2014 among 271 households in Thimbirigasyaya, researchers found that legal literacy regarding abortion laws were poor. Only 11% knew the law accurately. Their attitudes regarding the legalisation of abortion was that more than 50% held the view that abortion should be permitted for rape (65%), incest (55%) and lethal foetal abnormalities (53%). Only 4% thought it should be permitted at the request of the woman.

Proposals for liberalising abortion

The current proposal is to decriminalise abortion in certain instances: rape, statutory rape (where the woman is under 16 years of age), incest, and where the foetus has congenital deformities. Attempts have been made to reform these laws in the 1970s, in 1995 and in the present moment as well.

While these proposals seem to be a practical method of demarcating boundaries its implementation might not be so practical. Even if one were to assume that the legal system is efficient and fair (which it is not, as evident in different studies that have been carried out in Sri Lanka), would a legally valid determination re incest or rape be available based on which abortion could be permitted?

Generally, it takes at least 10 years for a Court to conclude a criminal trial – clearly these time frames do not match. Moreover, is abortion to be available at any point in the pregnancy in these circumstances? What  procedures are to be adopted in determining congenital deformities? What are the implications of these reforms to the medical profession? For instance, if a doctor refuses to perform an abortion would such doctor face civil or criminal liability? More information should be made available in the public domain in this regard in evaluating these proposed reforms.

procedures are to be adopted in determining congenital deformities? What are the implications of these reforms to the medical profession? For instance, if a doctor refuses to perform an abortion would such doctor face civil or criminal liability? More information should be made available in the public domain in this regard in evaluating these proposed reforms.

Prevalence of abortion in Sri Lanka

Anecdotal evidence and studies conducted in Sri Lanka over the years clearly establishes that the prohibition of abortion by law has not prevented women opting for the same. A study in 2000 suggests that 741 abortions are carried out per 1,000 live births in Sri Lanka. 12.5% of all maternal deaths are attributed to illegal abortions making it the third most common reason for such deaths in Sri Lanka.

Research carried out in two abortion clinics in Colombo in 1997 show that more than 90% of the clients of that clinic were married women. More than half of them already had had one or two children. Most of them were at the early stage of their pregnancy.

The reasons for the abortion among the married women included the pregnancy being too soon after the last delivery, poverty and foreign employment. Shame and fear were given as reasons by the unmarried women and the other reason given was that the father of child was not able/willing to marry the client. Most of the clients are reported as not having used a contraceptive method at the time of pregnancy. The authors of the study suggest that for a majority of the clients that were interviewed, abortion is used as a method of contraception, pointing to the need for improved family planning services.

A more recent study (2014) notes that use of contraceptives have increased in Sri Lanka from 32% in 1975 to 68% by 2006-7. However, abortion continues as a method of birth control at a rate of 45 per 1000 women. The women who participated in the 2014 study were women who had undergone unsafe abortions and women who had delivered children following an unintended pregnancy.

In this study it was found that lack of access to reliable information was one factor that pushed women to undergo unsafe abortions. From the women who delivered their children though the pregnancy was unintended, religion and ethical belief were given as factors that prevented them from opting for abortion more than the illegality of abortion.

Birth control and education on reproduction

The ineffective use of birth control methods seems to be the main reason for abortion in Sri Lanka. In a study published in 2007 for which data had been gathered from 306 abortion seekers, 74% had been using a contraception method at the time of conception. Of the women who were using contraception,traditional methods (‘safe period’ and withdrawal) were being used by 74%, thereby suggesting that information and decision making in selecting and using birth control is not as effective as it could be in Sri Lanka. Furthermore 68% of this group stated that they had no knowledge of emergency contraception methods.

Drawing on these findings it has been pointed out that proposals for liberalising abortion in Sri Lanka will not reduce the incidence of abortions as the factors leading women to seek abortion are not addressed by the proposed reforms. The proposals seek to permit abortion in instances of rape, incest and congenital deformities of the child – i.e. pregnancies under special circumstance. Most abortion seekers however are woman who seem to be becoming pregnant under ‘regular’ circumstance such as married women conceiving a third child. The mismatch between the proposals and reality is stark.

Irrespective of whether abortion laws are to be liberalised or not, Sri Lanka should focus on strengthening its reproductive health related services in general and sex education in particular. Sex education must be ensured at school level so that children grow up equipped with the knowledge and attitudes that is necessary to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

Women and abortion

Electing for an abortion has been recognised, with conditions, as part of a woman’s reproductive rights. In KL v Peru decided in 2005 by the Human Rights Committee (which is the Committee that monitors the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights) the Committee held that the refusal to carry out an abortion where the woman was carrying an anencephalic foetus was a violation of several human rights. In this case, the woman delivered the baby who died four days later.

The Committee decided that the refusal to carry out an abortion was a violation of the woman’s right to be free  from torture including mental torture, and the right to privacy. In 2015, the woman was granted compensation by the Peruvian Government for the violation of her human rights.

from torture including mental torture, and the right to privacy. In 2015, the woman was granted compensation by the Peruvian Government for the violation of her human rights.

In June 2017, the Human Rights Committee held that Ireland had violated the right of a woman to be free from torture, right to privacy, and freedom from discrimination in the case of Whelan v Ireland where the woman was denied abortion of a foetus that was diagnosed with a fatal foetal impairment.

While some countries such as Canada recognise a woman’s right to abortion at any point in the pregnancy, several other countries recognise a conditional right – which means that the woman’s right to an abortion reduces and is eventually eliminated as the pregnancy advances; based on circumstances of the conception; or based on health factors.

But the claim that women have a right to abortion is being challenged by different quarters. Of these, the most compelling argument is that abortion amounts to murder and should therefore continue to be a criminal offence permitting it only when it is a threat to the mother’s life. The following questions and issues are relevant in evaluating this claim.

When does life begin?

The advancement of science and technology has meant remarkable transformations in the field of human reproduction but it has not been particularly helpful in determining whether there is a particular point at which life begins.

Fertilisation itself does not happen in an instance but from the time the egg is fertilised it can be argued that the fertilised egg becomes a distinct organism (distinct from the egg or the sperm) which has the genetic makeup to develop into a human being. The ‘personhood’ of this living organism takes various forms throughout its lifetime. After birth it ranges from infancy to youth to adulthood to old age. Similarly, the stages before birth would range from a zygote to a foetus.

The point to note here is that personhood is not a stage in life that humans enter into and exist in clearly defined terms but is rather a stage that we evolve into and out of. So life ought to be recognised as such even when it does not demonstrate ‘personhood’– aperson with intellectual disability or a person in a coma are examples that illustrates this point.

If rights are accorded to human beings on the basis that they have an inherent right to it and not because they earn it – it becomes difficult to deny such rights to a human life pre-birth. However the only international human rights document that takes this approach is the Inter-American Declaration on the Rights and Freedom of Man which recognises that life begins at conception.

This is why the debate on abortion is actually a debate about the choices society makes about when it recognises a life, the autonomy it chooses to afford to a pregnant woman and the value it attaches to different types of life. Religious belief, cultural beliefs and practices, economics, politics weigh in significantly in these decisions.

Regardless of the position that we take on how law should regulate abortion – I do think it is necessary to recognise that life begins before birth. Not recognising this can have grave implications for protection of life in other instances including in old age and in relation to disabilities.

Law and life

It is helpful as this point to note that law heavily regulates our notions of life; when it begins and when it ends; the value of life; hierarchies in the value attached to life; and then of course the quality of life. It is not only abortion that can result in loss of life, and particularly loss of vulnerable or voiceless lives.

A country’s criminal justice system in and of itself, at a widespread and cross generational level can bring about similar outcomes. A casual glance at the prevailing realities of Sri Lanka’s access to justice particularly in criminal justice is a case in point. So while valid questions may be raised as to whether a zygote/embryo/foetus should have a right to life, those questions and concerns must be viewed as being connected to the other ways in which law (and its practice) impacts on fundamental questions about life.

Politics of abortion

The liberalisation of abortion has often been welcomed as an advancement of women’s equality and as recognition of women’s reproductive rights. The liberalisation of abortion means that the law will recognise the woman’s right and freedom to make choices with regard to whether she will carry through with her pregnancy.

Catherine Mackinnon, a path-breaking feminist legal scholar, writing in the 1970s about abortion laws argued that relegating abortion to the private sphere – i.e. giving the woman the ‘choice’ within a larger patriarchal context where women continue to be unequal and discriminated against, could often lead to further victimisation of women.

Recognising a woman’s right to privacy in this context she argues assumes a freedom and equality in the private sphere for a woman while the reality is different. In her own words ‘abortion promises women sex with men on the same terms on which men have sex with women… sexual liberation in this sense does not so much free women sexually as it frees male sexual aggression.’

Therefore if the objective is to improve respect for women’s equality and freedom in reproduction, the abortion debate must be seen as linked to other issues. The spread of underage marriage of the girl child, the stigma attached to pregnancy of ‘unmarried’ women, the applicability of personal laws that arediscriminatory of women and the prevalence of sexual harassment and domestic violence are some examples.

A debate with no winners

Whichever way the abortion debates move, it is a debate without winners. We are aware of how an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy affects a woman’s life. We are also aware of the lack of support women experience in rearing their children even where pregnancies are planned and expected.

Not allowing women who have been subject to rape or incest the freedom to decide whether they wish to have an abortion seems unacceptable. It is possible that some women chose to abort pregnancies where the child has a congenital defect because they feel that the rest of their family would be affected in serious ways in terms of care and availability.

However if you believe that one measurement of a society’s commitment to social justice and equality is the way in which it protects its vulnerable and marginalised, and if you believe that life does being at birth – then accepting abortion under the law becomes difficult.

Selective dispensability of life in proposed reforms

The logic of the proposals for liberalisation of abortion in Sri Lanka are not aligned with a recognition of women’s rights. None of the conditions that are proposed are in fact proposals that are being made in the interest of women’s equality. I say this for the following reasons.

This is the most problematic aspect of the current proposal at a normative level. It assigns a negative value to life that is ‘abnormal’, or ‘unacceptable’ life that is conceived in conditions of rape or incest and life that is conceived by girls under the age of 16. In a society that hardly recognises the human rights of persons with disability however, the proposal to permit abortion in cases of congenital deformities is not surprising. Persons with disability are generally invisible in Sri Lanka and this proposal seeks to ensure that their invisibility becomes a matter of policy.

In the case of rape, incest or statutory rape, the rationale seems to be that the woman had no choice in conception. But there are other underlying concerns – achild born out of such circumstances is considered to be unwanted, stigmatised and outside of the conventional institution that is allowed to procreate – i.e. marriage.

It can be argued therefore that the current proposals for liberalisation of abortion do not really uphold women’s right to privacy or right to reproduction. Rather these proposals reflect problematic assumptions that are made about the value of life, who has the right to procreate and who has a right to ‘be born’.

Any law that seeks to promote women’s rights should allow for abortion on more ‘liberal terms’. That is to say that the scheme should be based on a woman’s choice and the decision that society makes about when it would introduce a near absolute protection on human life before birth.

Law as lowest common denominator

Law almost always reflects some kind of belief – whether religious or not. The debate on abortion in Sri Lanka is also a debate as to whose belief should be reflected in this particular law. Exchange of ideas on social media suggests that there are at least two views – one which favours the prevailing law due to religious reasons and the other which supports the proposed reforms. The latter group rejects many of the ‘religious’ views on this matter. I do think that both these groups have to reflect on the extent to which they wish to impose their view on the rest of society.

Another way to look at this issue is to recognise that all things considered, the law is not a helpful tool which can help society in this regard. Abortion continues today regardless of criminal sanctions against it. However, that does not necessarily mean that one has to have a qualified view as to when life should be given legal protection.

Those who strongly oppose abortion should engage meaningfully in making their own choices and in helping society to improve in how these choices are made. But we do live in a society in which we have come to realise that we need to respect individual choices – sometimes even if we think their choices are wrong and harmful to society.

As much as I am a proponent of human dignity and equality, in making this argument, and as much as I believe that life begins at conception, I am compelled to make a ‘pro-choice’ argument for another reason. Pregnancy is a miracle – every single time – regardless of its circumstances and regardless of the health, ability of the life thus conceived. But it is a miracle that requires tremendous commitment, courage, and capacity on the part of the woman who has to bring forth that life or to raise that child.

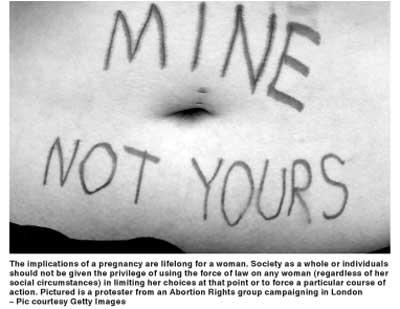

The implications of a pregnancy are lifelong for a woman. Society as a whole or individuals like me should not be given the privilege of using the force of law on any woman (regardless of her social circumstances) in limiting her choices at that point or to force a particular course of action.

(This article has benefitted from comments received by friends and colleagues).