Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 18 June 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Tamil politics is devoid of a strategic calculus. While the recent welcome offers to the Prime Minister and the President (in that chronological order) of conditional cooperation by the TNA leader Sampanthan

|

R. Sampanthan

|

|

A. Sumanthiran |

followed by its rising star Sumanthiran are healthy, positive gestures, the stipulated condition is unwise in the extreme: that of a new Constitution which accommodates Tamil aspirations. That’s been repeatedly tried and has failed. Worse: it’s a Pandora’s Box.

While it cannot be ruled out that the SLPP may be able to secure or come within striking distance of a two-thirds majority, any new Constitution that issues from it cannot but reflect the mandate as well as the larger ethos and the balance of forces, and these factors point to a neoconservative, ultranationalist, hyper-centralist Constitution, the very logic of which is structurally hostile to the principle of the sharing of power i.e. devolution. How can greater devolution get past the Buddhist Advisory Council? The counter-argument would be that the TNA’s support would be withheld unless the new Constitution met its requirements, but that’s riskily polarising.

Sinhala Far-Right Waves

Tracking the rise of the Sinhala Alt-Right would show a direct causal correlation with the project of seeking a new Constitution to further accommodate Tamil aspirations.

There were two waves of the rise of the Sinhala New Right. The first was the campaign triggered by the Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga project of a political package (which achieved notoriety simply as ‘The Package’) of a “union of regions” i.e. quasi-federalism.

Despite the handsome electoral victories of President Kumaratunga in 1994 and 1999, the resistance was widespread, sustained and successful, finally feeding into the Mahinda Rajapaksa candidacy and its victory of 2005, precisely because it was so far outside the parameters of the publicly acceptable. Unlike today’s GR Presidency however, Sinhala Buddhist ultra-nationalism never dominated the MR Presidential agenda, as evidenced by the fact that the Anti-Conversion Bill was taken off the table precisely by President MR.

The second wave was against the Ranil-Mangala endorsed Geneva 2015 resolution and the new Constitution project. Consensus was present for the 19th Amendment; a consensus ranging from the UNP through to the JO, mediated by President Sirisena and negotiated by the SLFP team led by Nimal Siripala de Silva and the JO parliamentary delegation led by Dinesh Gunawardena. The sole dissenter was Far-Right MP Admiral Sarath Weerasekara. It raised no more than a ripple on that occasion.

The wave reached tsunami proportions when the constitutional effort was driven beyond the reformist 19th Amendment towards a new Constitution seeking to override or by-pass the unitary character of the State.

A new Constitution would be necessary for Tamil aspirations only if these envisage a fundamental change beyond the 13th Amendment and/or in the unitary character of the state. The assumption that such drastic transformation is possible through the Prime Minister, who when he was President could/would not entertain any such possibility, and a President surrounded by fanatically anti-devolution Buddhist clergy and ultranationalist ex-military brass, is utopian.

Having surfed the Sinhala wave, it is improbable that either President Gotabaya Rajapaksa or Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, aware of the tragic fate of their father’s leader S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and the quarter from which it came, would risk the rage of the ultranationalist constituency led by the political bhikkhus, while also risking an opening for defeated parties by accommodating Tamil aspirations that venture beyond the constitutional status-quo.

It was the UNP that marched, led by JR, against the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact in 1957, empowered Cyril Mathew’s racism from 1977 to 1983, burnt CBK’s August 2000 constitutional draft in Parliament (while leader Ranil watched gleefully), and the oppositional SLFP propelled by Mangala Samaraweera and Anura Bandaranaike that allied with Wimal Weerawansa and the JVP in mobilising the nationalist wave that enabled CBK to topple the Tiger-appeasing Wickremesinghe in 2003.

Hoole stop the reign?

Today’s demonisation of Prof. Ratnajeevan Hoole and his young (Oxfordian) daughter by mainstream Government politicians is redolent of the atmosphere in which Cyril Mathew was on the warpath.

Prof. Hoole, probably the only Sri Lankan who has earned a DSc., was invited by President Mahinda Rajapaksa to be the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Jaffna. Prof. Carlo Fonseka was present. It was stymied because Tamil Hindu ultras lobbied the EPDP against Hoole, a Christian, and (against my  urging) Devananda swayed MR. The SLPP’s invective against Prof. Hoole show how far things have deteriorated since that invitation. The opening paragraph of an article in the Sunday Observer for President GR’s birthday, authored by Rear Admiral Shemal Fernando, PhD., further reveals the re-set of discourse:

urging) Devananda swayed MR. The SLPP’s invective against Prof. Hoole show how far things have deteriorated since that invitation. The opening paragraph of an article in the Sunday Observer for President GR’s birthday, authored by Rear Admiral Shemal Fernando, PhD., further reveals the re-set of discourse:

“… following his vigorous leadership as the Defence Secretary to eradicate the cruellest terrorist organisation in the world, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam…” (http://www.sundayobserver.lk/2020/06/14/opinion/patriot-committed-transform-country)

This revisionist history omits the objective truth that President Mahinda Rajapaksa was Minister of Defence and Commander-in-Chief during the war and provided overall leadership.

It is in such an ideological matrix that the TNA absurdly hopes to secure a new Constitution that meets Tamil aspirations.

Avoidable spikes and surges

The two waves of the Sinhala New Right were hardly inevitable. With the support she enjoyed from India, the Left and a moderate UNP Opposition, all President CBK had to do was follow-through sincerely on implementation of the 13th Amendment together with the “residual matters” that were tabled by India and Sri Lanka in late 1987. India never pushed beyond that. She had the best chance of winning the war, especially after the assassination attempt on her in December 1999 and the global shift on terrorism in 2001 with 9/11. When the first wave smashed through in 2004-5 it was against Ranil’s collaborationist CFA with Prabhakaran, the ISGA prospect, and CBK’s PTOMS.

The second wave that crested in late-2019 was also avoidable. The first rumblings of the tectonic shift were detectable during President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s second term. Negotiations with the TNA commenced belatedly, in 2011 and the TNA, widely perceived as political fellow-travellers of the defeated and detested LTTE, declined to regard the 13th Amendment as framework or even as basis of negotiations and put forward proposals on the emotive issue of land which went beyond it.

The next rumbling of the tectonic plates could be heard in 2013, when the newly elected Chief Minister of the Northern Provincial Council released a statement reiterating his commitment to “self-determination” (which in Kashmir, was risky for a Chief Minister even under Nehru and Indira). The conversion of Gotabhaya Rajapaksa from an agnostic on the 13th Amendment during the outbreak of the war at a time Chief Justice Sarath Silva was lobbying Basil and Mahinda Rajapaksa for adoption of the district as the unit of devolution, to one who regarded devolution as dangerously centrifugal, was catalysed by such reckless provocations.

The Tamil political imagination

In an important sense it is unfair to criticise the TNA without acknowledging that its unrealistic stances have been driven by Tamil political consciousness and the attempt to log-roll on the currents of that consciousness.

Writing as one whose first published interventions on the Tamil Question date back to the Lanka Guardian issues of June-July 1979, triggering a polemic with Dr. Kumar David, 41 years ago (when I was 22), I seek to raise a few questions for reflective consideration and present provisional answers for consideration:

I. What is the highest or peak political achievement of the Tamil people?

II. What if Prabhakaran had been alive today?

III. What if those liquidated by Prabhakaran had been alive today?

IV. What, if any, is the change in the balance of forces that permit the surpassing of that peak achievement?

V. If a Tamil public personality could be brought back to life today, who should it be?

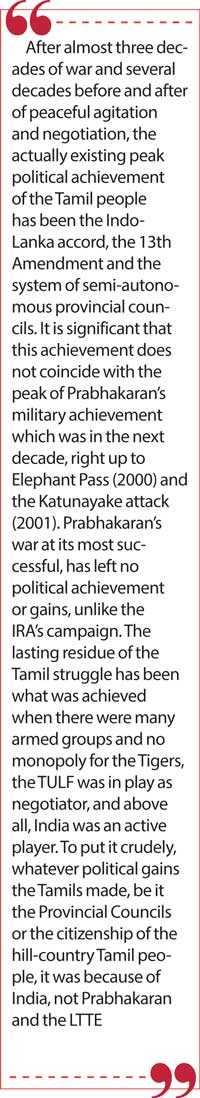

After almost three decades of war and several decades before and after of peaceful agitation and negotiation, the actually existing peak political achievement of the Tamil people has been the Indo-Lanka accord, the 13th Amendment and the system of semi-autonomous provincial councils. It is significant that this achievement does not coincide with the peak of Prabhakaran’s military achievement which was in the next decade, right up to Elephant Pass (2000) and the Katunayake attack (2001).

Prabhakaran’s war at its most successful, has left no political achievement or gains, unlike the IRA’s campaign. The lasting residue of the Tamil struggle has been what was achieved when there were many armed groups and no monopoly for the Tigers, the TULF was in play as negotiator, and above all, India was an active player.

To put it crudely, whatever political gains the Tamils made, be it the Provincial Councils or the citizenship of the hill-country Tamil people, it was because of India, not Prabhakaran and the LTTE.

What if Prabhakaran had been alive today? At their peak, and in the “Final War” of his choosing (postponed by a year due to the tsunami), Prabhakaran and his army were ingloriously decimated by the Sri Lankan military. The leader who saved him from the SLA in 1987, Rajiv Gandhi, was murdered by Prabhakaran in 1990. With today’s ruthless resolve and doctrines of zero-tolerance and pre-emption, any sign of armed militancy would be extirpated.

What if those murdered by Prabhakaran had been alive today? Amirthalingam, Mr. and Mrs. Yogeswaran, Sam Tambimuttu, Neelan Tiruchelvam, K. Pathmanabha, Gopalaswamy Mahendrarajah (aka ‘Mahattaya’), Kethesh Loganathan, Rajini Tiranagama and Lakshman Kadirgamar, to name just a few. If any one of them, let alone several or all, had been alive today, Tamil political strength and prospects, in the north and south of Sri Lanka and worldwide would have been vastly and qualitatively better.

So, which was the greater loss to the Tamil political cause, Prabhakaran and his Tigers, or those he murdered? Who could have contributed more to the Tamil political cause and project had they been alive?

In the Tamil political memory, the drama of Prabhakaran’s war, though utterly lost, is felt to have achieved more for the Tamils than that of India’s intervention both diplomatic and military, which is logically impossible because no irregular force that fights to the finish and loses completely instead of successfully resisting like Hezbollah and Hamas or stopping and settling for feasible reforms like the IRA/Sinn Fein, can possibly equal the impact of the conventional military of a strong, established state.

The Tamil mythic imagination notwithstanding, the reality was that India’s Mirage 2000s inevitably achieved more for Sri Lanka’s Tamils than did all of Prabhakaran’s suicide-bombers, snipers, artillery units, Sea Tigers, and miniature air-force.

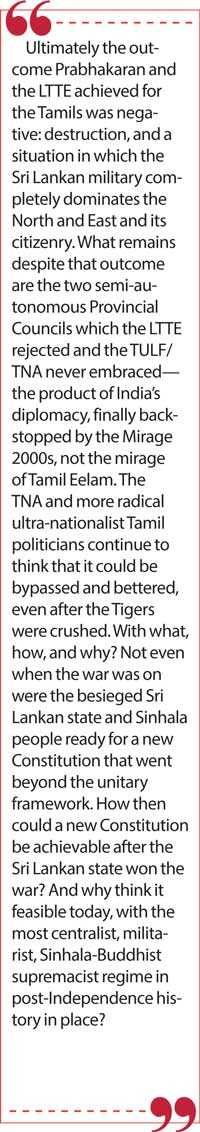

Ultimately the outcome Prabhakaran and the LTTE achieved for the Tamils was negative: destruction, and a situation in which the Sri Lankan military completely dominates the North and East and its citizenry. What remains despite that outcome are the two semi-autonomous Provincial Councils which the LTTE rejected and the TULF/TNA never embraced—the product of India’s diplomacy, finally backstopped by the Mirage 2000s, not the mirage of Tamil Eelam.

The TNA and more radical ultra-nationalist Tamil politicians continue to think that it could be bypassed and bettered, even after the Tigers were crushed. With what, how, and why? Not even when the war was on were the besieged Sri Lankan state and Sinhala people ready for a new Constitution that went beyond the unitary framework. How then could a new Constitution be achievable after the Sri Lankan state won the war? And why think it feasible today, with the most centralist, militarist, Sinhala-Buddhist supremacist regime in post-Independence history in place?

Waiting for Biden

The US Election Unit of The Economist (London) gives President Trump only a one-in-five chance of winning.

The Trump experiment is already melting-down the myth of the superiority or even the adequacy of a President who has zero-political experience but has been successful in other spheres. The polarising Bolsonaro experiment is also exposing the ‘ex-military Far-Right President’ model.

By contrast, President Erdogan, Prime Minister Modi and President Duterte who belong to a distantly related ideological family, remain sustainable political successes due to their organic populism evolved through long political experience, accumulated instinct and flexibility as persuasive ‘political animals’. Populism, even rightwing nationalist-populism, and militarism (military-supremacism/military-centrism/military-domination) as in the GR model, have very different DNA.

In Sri Lanka we are still at the beginning, not the end or even the middle of the Trumpian Far-Right arc, though its bending will be accelerated and its life-cycle foreshortened to a single term as was Madam Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s two-thirds majority based 1970 government, by the likely end of the Trump administration and its replacement by a progressive-liberal Biden Presidency. Tamil political prospects could improve if Kamala Harris makes the ticket or as by-product of a more coherently coordinated Indo-US policy in the greater region in a post-Trump international order, especially after the recent Indo-China border clash, but none of that can secure the Sinhala vote at a referendum for a non-unitary/post-unitary Constitution.

Any new global and regional factors the Tamils can leverage should be in the service of “building on” that which was achieved for the Tamils by India in 1987, because any externally-imposed sundering of the unitary character of the state even under a different dispensation is likely to generate a Sinhala-Buddhist Taliban equivalent issuing from within a tough, nationalist military, rendering the island an ungovernable quagmire.

Today, the solitary ‘plus’ factor in the Sri Lankan scenario is that the “enemy image” that Sinhala chauvinism has repeatedly, ferociously, fed on, the Ranil-CBK-Mangala neoliberal project/ bloc is almost eclipsed, permitting the progressive-populist (“pragathisheelee, podujanavaadee” as Sajith calls it) New Opposition to lead the fight for democracy and defeat the Far-Right by the end of a single term.

A new Constitution now would only enthrone Sinhala-Buddhist supremacism. No mainstream Opposition would dare confront it and no successor administration would dare undo it (as 1978 never undid the 1972 redefinition).

Even with a Biden win and a fresh Indo-US approach, Tamil standing will not be helped by fealty to a history, memory and symbolism of terrorist violence. Imagine the wider appeal and greater impact that MIA could have if she dropped the petulant infantile identification with Tiger terrorism (which my late friend, her Marxist father Arular of EROS, never endorsed).

As in Avengers: Endgame, if it were possible to retrieve a lost Tamil personality from the past, who would be most suitable and useful? Had Corbyn won, the answer would be Balasingham, but enlightened Tamil self-interest in a post-Trump, post-COVID world would be best served by “restoring” –rediscovering, studying, emulating – a non-violent, scholarly victim of Prabhakaran’s suicide-bombers and arguably the Bobby Kennedy of Tamil politics: Neelan Tiruchelvam.

The political meta-narrative of heroes, martyrs, traitors and villains in the Tamil consciousness, including in the Diaspora, needs to change, through an audit and accounting of the whole of contemporary Tamil political history. Far from being the heroic successor of S.J.V. Chelvanakayam, Velupillai Prabhakaran was actually the great deviationist, and executioner of Chelvanayakam’s authentic, gifted political children.