Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 5 November 2018 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

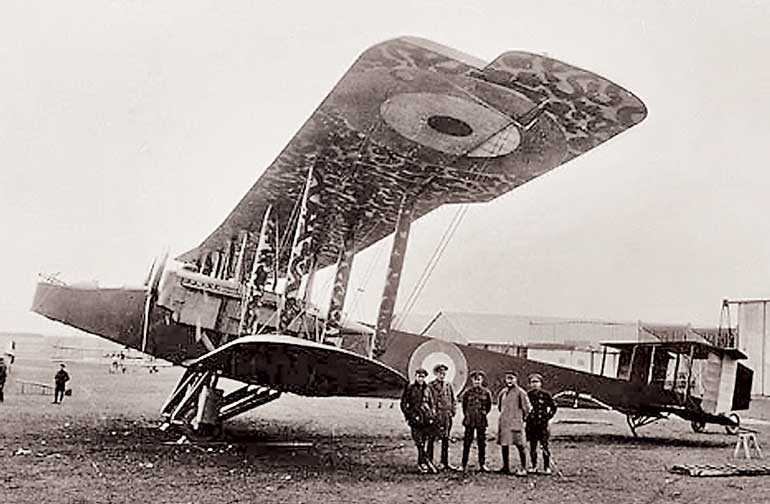

A Handley Page O/100 of the Royal Naval Air Service

A Sikorsky Ilya Mourometz

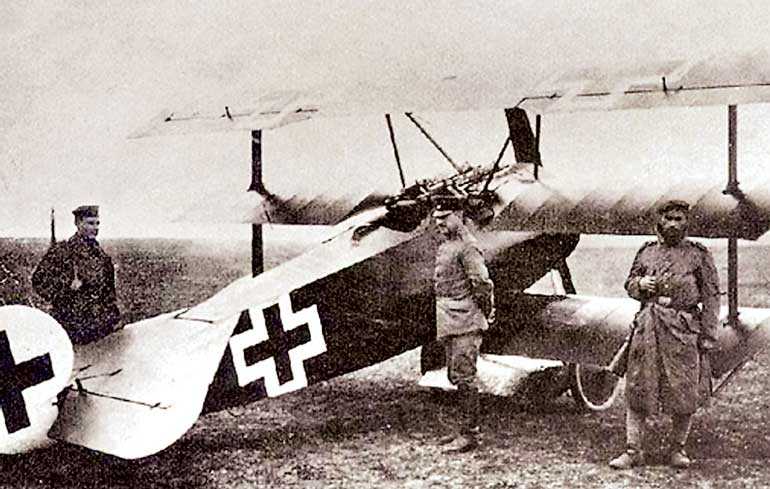

Baron Manfred von Richthofen’s all-red Fokker Dr.1 425/17 shortly before his demise

The Great War, which engulfed Europe in August 1914, was supposed to be a short conflict “over by Christmas” in the opinion of the complacent Generals who planned it. In fact, the first sustained conflict between industrial powers turned into a quagmire of unparalleled horror and savagery, which was to last over four terrible years.

The public at home greeted the sheer awfulness of the trench warfare that resulted in a long stalemate with revulsion. The new air forces provided a distraction. Both sides used the ‘knights’ of the air as propaganda tools, with tales of bravado and skill in piloting their newly developed ‘fighters’ against each other. Fighter pilots such as the Baron Manfred von Richthofen, the German nobleman who was the greatest of them all, along with colleagues such as Ernst Udet and Erich Lowenhardt, were made into legendary heroes. They were joined by pilots on the Allied side such as Rene Fonck, Billy Bishop, Alec Ball and Edward Mannock, to be promoted as the chivalrous heroes bedecked in leather jackets and silk scarves, a ray of decency in a war that lacked all honour.

In actuality, the lifespan of these ‘aces’ was quite limited, with almost all of them dying after a short period of time. The fur-lined leather jackets barely kept out the brutal cold of the open cockpits and the scarves were used to prevent inhaling the noxious oil that lubricated their primitive engines. Glorious it was not, but certainly better than the absolute horrors experienced in the trenches.

Rapid innovation

The innovation on the technical side, however, continued in leaps and bounds. Renowned designers such as Fokker (who made Richthofen’s famous Tri-plane), the British companies Sopwith, the Royal Aircraft Factory and Bristol Aircraft, France’s SPAD and Nieuport had all started to produce very capable and effective machines. The Americans, despite the pioneering efforts of the Wrights, had fallen way behind, with only the Curtiss ‘flying boats’ seeing active service in the war.

While glory and attention were trained on the small single-seat fighters, great strides were also being made with larger aircraft, most often used for bombing. The exigencies of war allowed for huge research and development budgets. Aircraft designers responded with many innovative designs, particularly for fighters and bombers – weapons of aggression that were designed to break the stalemate on the ground.

Interestingly, little effort was expended on developing transport aircraft, with trains and ships remaining the principle mode of carrying heavy loads over long distances. The engines and structures of the aircraft, still mainly wood and canvas, did not allow for significant payloads to be carried aloft.

The German side developed the Gotha, a large twin-engined machine capable of bombing Britain. The British in turn had the Handley-Page O/100 but it was the Russians who developed the ‘Ilya Mourometz’, the world’s first four-engined aircraft, designed by Igor Sikorsky (this talented inventor was to flee Russia after the revolution and became famous as a legendary helicopter designer based in the US in later life).

The Germans also used the lighter-than-air Zeppelins, which were modified for carrying bombs. These were to enjoy a brief period of civilian use after the war in the 1920s and 1930s, before the Hindenburg disaster put an end to these graceful aircraft.

War’s end

The Great War, as it was known, ground to a halt in November 1918 after four long and terrible years. The conflict killed an estimated 9-11 million military personnel and another eight million civilians. Astonishingly, a further 50-100 million died in the Spanish Flu epidemic that followed soon after the war. Even Ceylon, despite its isolation, suffered over 307,000 deaths, an estimated 6.7% of its population at the time.

By its end, four great empires - the Turkish, Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian - were destroyed and dismembered. The maps of Europe were dramatically changed and society was never the same again. Aviation too had changed in spectacular fashion. The frail hand-built machines of 1914 were replaced by much more capable aircraft coming out of factories in large quantities. A golden age of commercial aviation was about to begin.