Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 16 April 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

As the Head of the Sri Lankan Catholic Church, the Cardinal’s anger is righteous; he demands justice, not only for the perpetrators of the outrage, but also for the so-called authorities, those who stood and waited, either through their customary dithering or timorousness, or the buffoonery of men simply unequal to the challenges of today’s world

“Nobody can rule guiltlessly” – Saint-Just

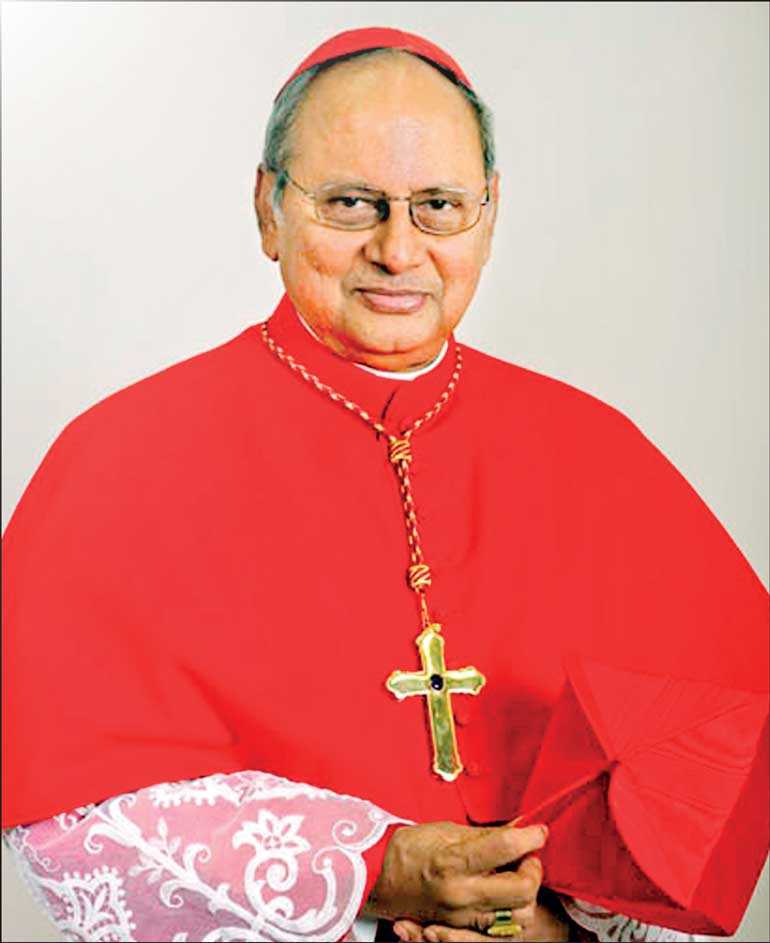

Archbishop Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith’s discontent is obvious; his every statement underlines his dissatisfaction. In the Easter Sunday outrage of 2019, in addition to plush Colombo hotels, several churches were targeted, hundreds of innocent worshippers fell victim to the coordinated attack of the suicide bombers on that day.

Archbishop Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith’s discontent is obvious; his every statement underlines his dissatisfaction. In the Easter Sunday outrage of 2019, in addition to plush Colombo hotels, several churches were targeted, hundreds of innocent worshippers fell victim to the coordinated attack of the suicide bombers on that day.

Not only were the attacks indescribably inhuman, they were senseless; men, women, children, harmlessly going about their prayers perished in one blinding flash; and, none could answer why.

As the Head of the Sri Lankan Catholic Church, the Cardinal’s anger is righteous; he demands justice, not only for the perpetrators of the outrage, but also for the so-called authorities, those who stood and waited, either through their customary dithering or timorousness, or the buffoonery of men simply unequal to the challenges of today’s world.

We need to only look at Sri Lanka’s present situation, political, social as well as economic, to comprehend the appalling quality of leadership the country has produced post-independence.

What the common perception in this country considers leadership, is a tragicomedy, tailored to meet a very basic mentality. As a result, the prevailing culture seemingly favours a certain type of personality in every sphere of public office, enabling only careerists in the lowest sense; mediocrities, windbags, and nepotistic fraudsters rule the roost. No wonder that the Cardinal wants them dealt with.

The word nepotism apparently has a Latin root, ‘nepos’ meaning nephew. Until the late 17th Century when by papal order the Popes (and other high officials) were banned from bestowing estates and offices to relatives, it was a common practice to pass on such favours to close relatives. Several Popes elevated their nephews to high office in the church, some even succeeding as Popes themselves (it had to be nephews, as on account of their oath of celibacy, they were deemed to have sired no children).

Nepotism, the evil that the church confronted and attempted to stamp out four centuries ago, has in this 21st century become a fetish in Sri Lanka, every politician striving to create a succession plan for his kith and kin! There is no strong moral objection from the wider society, even in the ranks of the rebels; the NGOs and other social organisations, family connections are rife. Our political parties go from father to son, mother to daughter, brother to brother, uncle to nephew, a mere bequest.

Going back to the Easter outrage, it is a truism that one is wise after the event. From the widespread plane hijackings of the 1970s to the course changing 9/11: these were atrocities the security services of those countries did not anticipate, thus, were unable to prevent. Afterwards, the entire world took steps to cover terrorists from using these methods. Security at today’s airports are near impenetrable. Invariably, the first time, is the most difficult to forestall.

Equally, the instinctive reactions of men to any large, sudden and traumatic phenomenon, cannot always be faultless. Under the pressures of fast developing events, their automatic responses will not necessarily be the most rational. To take a hypothetical situation, let us say a future Government appoints a Presidential Commission to inquire into the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic by this Government, a phenomenon which has resulted in the death of hundreds while damaging an already-vulnerable economy near fatally.

Several questions can be asked; were all necessary steps taken to close our borders in time, how did COVID-19 clusters such as at the fish market and Navy camp develop later, was the inoculation properly organised, did the long and blanket lockdown achieve its purpose, what was the economic impact, how well advised was the decision to ban burials?

The so-called authorities are also human, and likely to err. There is a saying that the best is the enemy of the good; if we insist on the perfect solution for every problem, we will perhaps miss many opportunities to provide good solutions. Too much nit-picking and fault-finding can only demoralise an administration.

Is every non-action, an abdication of authority? Acts of omission are distinguishable from acts of commission. The political decision maker has many aspects to consider: the economy, social impact, racial harmony, legality and above all, his voter base; considerations that are bound to influence any decision he makes.

A serious study of intelligence gathering in other countries will reveal its essential volatility, many a security warning has turned out to be damp squibs. If the authorities mobilise at every such warning, we would be on a permanent war footing. In the shadowy world of the intelligence operatives, misinformation, faulty interpretation, false trails, provocateurs and double agents are familiar features.

We remember the embarrassing incident during the harrowing days of the JVP insurrection of the late 1980s when Defence Minister Lalith Athulathmudali was duped into declaring a ceasefire by a fraudster claiming to be a representative of the clandestine movement, then wreaking havoc in the country. Athulathmudali, much better educated and more urbane than the average politician, was taken in by the man’s pretence, a clear case of an intelligence failure. Even for a high calibre leadership, handing intelligence received is challenging work, requiring extreme discernment, sensitivity and caution.

All this does not mean that our leaders are free of guilt. When their acts of commission are gaping blunders costing colossal sums of money for the country, for their acts of omission the price is paid with the lives of hundreds of citizens, they insist on round the clock security for themselves, and claim every privilege that power can bring, the case against them, at least where ineptness and corruption are concerned, is open and shut. Our so-called leaders, offend the meaning of leadership.

Many want to believe that there are several layers of intrigue behind Easter Sunday. They somewhat downplay the role of the suicide bombers to a status of pawns in a large and complex scheme, the dimensions of which even the perpetrators were only dimly aware of. This is speculative, having no knowledge of such convoluted conspiracies, we cannot comment any further.

The Cardinal wants the authorities to bring justice to those who are guilty of acts of commission as well as omission in relation to the Easter bombing. Undoubtedly, this will be the wish of all right-thinking persons, arriving at an appropriate measure of guilt being the only trouble. Outraged they may be, but agreeing on the culpability of those outside of the plot, is bound to raise serious controversy. Linking them to the crime may not be as easy as commonly assumed.

Having moved in that direction, the good Cardinal now perhaps realises that it is an arduous journey from the province of God to the province of Caesar. We postulate the kingdom of God in its perfection, we see the reality of life before us for its sham and shoddiness. The very authority we appeal to is the source of our unhappiness, the culture of our ruin. By this plea, do we legitimise that which is essentially corrupt and dubious?

“Justice is turned back, and righteousness stands far away; for truth has stumbled in the street, and uprightness cannot enter” – Isaiah 59:14.