Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 28 July 2020 01:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

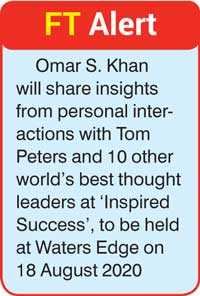

Having worked with the madcap maestro of corporate “vivification,” Tom Peters, having brought him to Sri Lanka, and collaborated with him and his company, I have an unrepentant admiration for his ability to be decisively and unerringly ahead of the curve.

When McKinsey sent Tom and colleague Bob Waterman out to do the research that led to In Search of Excellence, who could have guessed in the fusty and fussy corridors of corporate power that the realisation that “people matter,” that “getting close to customers” and exercising aptitudes like “simultaneous loose-tight properties” would so enthuse and excite the world … mired as that world was in plodding strategic planning and kowtowing to central planning and corporate hierarchy?

But Tom Peters has ruthlessly reinvented himself ever since, and continued to be a thought-provoking firebrand. And so, I’ve selected in this tour of his thinking and impact, what most captivated me during the time we interacted together … namely his challenge that if the world had truly gone “mad” (upending nostrums and notions of normalcy), then in an “insane” world, “sane” organisations no longer made any sense.

And if anyone looking at today’s COVID-splattered landscape, this bizarre brew of public health prudence and paranoia, the prurient manic over-reaction being fomented by various global media outlets, and the uncertain economic devastation still playing out, thinks “normal” is even a meaningful concept, then said person has clearly taken a treacherous leave of absence from their senses.

Asia leads again

Circa 1993, the world watched agog as the Chinese rioted to acquire stock share applications, as Singapore’s per capita income exceeded that of Britain, and electronic design work not just in Japan but Taiwan, Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, and yes, China and India, became truly world-leading.

The 90s were another turning point, as an “emerging” behemoth Microsoft’s stock market value exceeded General Motors for the first time (though Microsoft at the time had $ 2 billion in revenues and GM had $ 120 billion). And this is not the same phenomenon as Tesla today, as today’s “zero interest money” and central bank manipulations are creating all kinds of skews that may or may not last. But the 90s saw a foundational change in the very concept of value, which we are still exploiting and seeking to explore today. Tom Peters, as ever, was at the vanguard of pointing this out.

Restructuring revolutions began, and they sputtered and foundered later, as our “thinking” and “behavioural evolution” couldn’t keep pace with the opportunities and imperatives. We think AI might cost us jobs today, but HP (Hewlett-Packard), back then announced it could run it’s 9,000-person ink-jet printer business with “4” head office staff! Flattening and outsourcing were the mantras, and Tom was beating the drums of revolution, as he had from the early days.

Asia today leads again in pandemic responsiveness, results, overall leadership, and social cohesion. The world leader, the USA, now as then, is facing not only a crisis of confidence, but a crisis of identity. So, we may be “back” to the Tom Peters revolution again, and I want to explore how some of those “90s themes” are every bit as urgent and pressing once more.

The imagination quotient

Tom has pointed out that “soft” is “hard” in multiple dimensions. Nike became a global brand, like Harley Davidson, by entering the “lifestyle” business, not the shoe or motorcycle business.

3M intoned: “We are trying to sell more and more intellect and less and less materials.” That is the very essence of the modern economy. Microsoft is often considered “traditional” when compared with the explosively audacious and perpetually “revolutionary” Apple. But Microsoft is a venerable player, and yet even they made it clear: “Microsoft’s only factory asset is imagination.”

Tom challenges us anew: “If imagination and intellect and knowhow and design are an increasing part of the ‘value’ of brands and companies and experiences, who among us feels they understand how to ‘manage’ the imagination?”

And yet companies will moan and groan over capital expenditure proposals, and yet ignore all the “other,” the expertise, the team competencies and alignment or lack thereof, the growing or stunting of leaders, the creation of proprietary processes and embedding them in behaviours … this is a gaping chasm and it sums up the sheer shocking failure of large company after large company to sustain their eminence, or “icon” after icon, superseded by a creative disruptor who passionately “sweats” the adaptive “other.” It is the passion for the mortar, not just the bricks.

The joys of disorganisation

Companies went on a mania of decentralisation, from which they then recoiled later, when “trust” and “empowerment” were shown to be easier to preach than practice. But the benefits of a more federal approach became increasingly evident. The ineffectiveness and inefficiency of problems beginning a slow ascent “up” the hierarchy and then a slow agonising flow down, where the customer say who flagged the problem, if still alive, might finally hear back, became ever more evidently preposterous.

Of course, today, with disquiet going viral in seconds, pacifying has to take place immediately. But “solutions” are not frankly any faster or better, just the mollifying rhetoric.

Reducing management ranks without increasing line manager autonomy is also pointless. This also requires vastly simplifying procedures, removing layers of staff that add “negative” value to customer satisfaction and innovation, and activities that can be outsourced have to increasingly become so. Manufacturing as a result, has been, and continues to be, radically reinvented and reorganised.

And yet the aim of putting a “small company soul into a big company body” remains as elusive as ever Tom reminds us. The experiment conducted by Lakeland Medical Center in Florida, decades ago, creating “mini-hospitals” within a central hospital, and then creating “care pairs” who can provide 80-90% of pre and post-surgical care for 4-7 patients each (a registered nurse allied with a technician) proved dramatically successful: turnaround time for routine tests dropped from 157 minutes to 48 minutes – in diagnostic radiology, a 40 step, 140 minute process became an 8 step, 28 minute process; they had the lowest medication error rate compared to benchmark hospitals; registered nurse turnover plummeted; out of pocket costs fell; physician and patient satisfaction shot up; and nurses now could spend 51% of their time with a patient rather than a mere frustrated 21% while they battled their own bureaucracy. Yet this is hardly the norm today despite these overwhelming results.

Why does this still read like science fiction more than two decades later? Why does the mania for “self-destruction” at say, Intel, where rendering a market-leading product of their own obsolete, in pursuit of not only “disorganisation” but outright “self-destruction”, periodically still make us nervous rather than having us simply applaud with recognition?

In pandemic times, and pandemic aftermaths, “tinkering”, or “incrementalism”, or stodgy staleness hiding under outmoded business models and practices, will not work.

We need the zest for utter infatuated dedication to value, to customer, to focused “craziness”, to being willing and able to challenge virtually everything.

The “tired” will be the “dead,” those who are committed to ongoing spontaneous discovery processes, argues Tom, who ground that in their human capital and brand engagement, who accept temporary “failure” with wit, grace and style, will rebound.

We have to all be willing to build greenhouses in which to nurture the new order; we have to sharpen our capabilities and soften our more fixated strategic focus, and let an emerging future light the way, one we respond to and influence.

Liberating entrepreneurs and growing leaders at all levels

Tom reminds us that almost all good work is done at least “partly” in defiance of management; following orders as an excuse for delivering substandard results is sheer capitulation.

More businesses are giving workers their own “space” to manage, run, to steer the costs and deliver the profits from. If detached from business outcomes, they can only be a cog in the wheel. What we need to be doing in this shell-shocked world is selling relationship management, customisation and responsiveness. A key question to ask of every team, department, even units or roles: “How can this be ‘businessed’?”

So, metrics have to evolve. Here are some Tom campaigns for tracking, coaching, stimulating, assessing and then cheering:

And yes, we can cut costs by going virtual, but that won’t deliver growth. Growth will come from each of these folks “viscerally” being able and developed to deliver and having the terrifying “ownership” and the exciting upside that comes from being able to do so.

Eons ahead of his time, Roger Meade, then-CEO of IS firm Scitor, made the following a key plank of their corporate creed. How many companies would have the wisdom and courage to live by this, or even just publish it, lo these many years later? The creed stated:

“Utilise your best judgment at all times. Ask yourself: Is it fair and reasonable? Is it honest? Does it make good business sense in the context of our established objectives? If you can answer yes to all of these, then proceed. Remember you are accountable against this policy for all your actions. If you find that management’s direction is out of touch with the reality of the situation at hand, it is your responsibility to act based on your best judgment. Never, and I mean never, use the excuse of following orders as the rationale for following a poor course of action. This is compounding stupidity, and it is inexcusable.”

So, from this, you either will get potential anarchy, or bracing, proactive communication, dialogue, information sharing, and continuous alignment.

Tom also recommends that everyone have to “re-apply” for their job each year, and in order to justify that, as an independent contractor pitching for a job would, rather than just a KPI based performance review, the following should be presented:

For bosses the gauntlet is even more bracing … imagine you had to make yourself obsolete for at least 80% of what you currently do in 6 months, and the company had to be able to carry on these functions with no replacement for you. Present your game-plan and then deliver it. As Bill Chartland put it so unforgettably, “Jobs are joint ventures with an employer in problem-solving.”

Leverage knowledge and capabilities

Here is the paradox of the regional or global powerhouse in the emerging age, which is also locally savvy and relevant: Stay close to customers and supply chain and perform as responsive, semi-autonomous units and demonstrate value; and paradoxically realise as the powerhouse Asea Brown Boveri (ABB) championed lo those many trailblazing years ago: “Power stems from constant cooperation between units.”

Flowing from this is the realisation that “staff experts” are often not expert at all, and yet expertise is needed more crucially than ever. The “dispersed” organisation is next, where expertise is located not in central HQ with ludicrously pricey real estate to boot, but in whichever line operation it can best add value.

Why experts need to live as Peters says “cheek-by-jowl in a Brussels spire (or Beijing or Bahrain or Boston) and devote large chunks of their days to playing politics and brown-nosing nearby senior management,” is anything but self-evident. What if senior leaders were perceived to be in the “knowledge and opportunity transfer” business, rather than the “command and control” soul-leeching business?

And the “networking” of knowledge is not primarily about bits and bytes. State-of-the-art software packages have been around for some time, but most companies, from PwC to FMCG transnationals report they aren’t using these “aptitudes” in particularly interesting ways. The aim is nothing less than to convert everything from insurance companies to banks to hospitality brands to power generation firms to “an ensemble of interconnected communities of practice.” Collaboration, we are learning increasingly, is like romance, it can’t be routine and predictable, and it can’t be “ordered.”

What if we construed “work” going forward as “conversations” that need to take place, creating new value, exploiting strategic or even transient market openings? And what if enabling, stimulating, preparing for, conducting and following through and following on from those conversations became one of the core priorities and identifying marks of leadership? Then, “digital” could provide platforms and pathways, and what flowed through would be worth its weight in value and inspiration.

Welcome the weird

Sigmund Freud gave us sobering testimony: “What a distressing contrast there is between the radiant intelligence of the child and the feeble mentality of the average adult.” No wonder kids are so loathe to “grow up!”

Tom adds his own marvellous spice mixture: “Most organisations bore me stiff. I can’t imagine working in one of them. I’d be sad if my children chose to. Most organisations, large and small, are bland as bean curd.” Turnaround maven Victor Palmieri decries the fact that strategies are routinely okayed in boardrooms that most children would know are bound to fail.

Some ideas to reverse this trend:

The revolution continues and the myth of shareholder value

Tom has continued to be at the forefront of management thinking, from pushing us to consider all “work” to be raw material for conversion into “wow” projects, for individuals to consider themselves true emerging “brands,” to departments evolving into true “professional service firms,” for “design” as argued above to take increasing primacy, to leaders growing other leaders being a true conviction, to cultivating truly diverse leadership and drawing on women’s leadership, to understanding the extraordinary potential of marketing to women, to marketing to the older (discretionary income and time on their hands) … these are thunderclaps of change that are ever more needed … add to that the need to redefine “resilience” in a world that has to live with, live past, and learn to truly live beyond COVID-19 no matter the medical stats, which may continue to swell and sputter for some time.

And the concept that is truly dated, and the global financial crisis of 2008-9 left a lot of cynicism in its wake from the failure of global leadership to demand accountability here, is the single-minded, rapacious obsession with shareholder value.

449 S&P 500 companies publicly listed in 2003-2012, 54% of $2.4 trillion went to earnings/stock buybacks, 37% to dividends, and a shameful 9% for what were termed “productive capabilities or higher incomes for employees.” Bailed-out companies, instead of investing in future growth, cut capital expenditure and increased debt, and so COVID-19 is now interacting with a swelling corporate debt bubble.

Tom Peters cites Joseph Bower and Lynn Paine speaking about the “error at the heart of corporate leadership.” They point out that the alleged benefit from hedge fund activism beyond an initial stock price bump is rare. Far from waking up a sleepy board or driving an overdue change in strategy or management, what happens is less “value creation” than “value transfer.” Nothing is created, instead cash that would have gone to future returns now goes to dividends. The lag time though is such it exceeds the timeframes of standard models, and so the travesty is not “breaking news” as it otherwise would be.

The former Medtronic CEO sums it up powerfully: “… unconstrained capitalism focusing on short-term gains can cause great harm to employees, communities, and the greater needs of society …”

It is the breeding ground for much of the populism outbreaks around the world, and the “rigged” system anger, boiling over after the COVID-19 shocks and perceived helplessness are further testimony to this. This can be summed up under the following headlines, and Tom Peters’ current work is leading us to consider antidotes to the following:

“Too much cost, not enough value.

Too much speculation, not enough investment.

Too much counting, not enough trust.

Too much complexity, not enough simplicity.

Too much business conduct, not enough professional conduct.

Too much salesmanship, not enough stewardship.

Too much focus on things, not enough focus on commitment.

Too many 21st century values, not enough 18th century values.

Too much success, not enough character.”

(From the chapter titles of a book extolled by Peters called “Enough” by Jack Bogle)

The Tom Peters phenomenon

No one quite says it like Tom, the uber-guru, the epiphenomenon in the world of drab management theory. Here he is giving his own answer to his own ethos when being asked about “perpetuity” in Sao Paulo:

“I’ve ‘lasted’ quite a while; my landmark book, In Search of Excellence, arrived decades ago. That’s cool. But it misses the point ... utterly misses the point. I live for one ... and only one ... thing. The moment. I have worked my buns off at my craft for 3 decades, but the entire point is to do absolutely nothing more than bring every moment of those 30 years to bear on this ... this ‘mere’ 30-minute press conference in São Paulo. Screw the ‘long term.’ I will achieve impact in answering your particular question or ... as I see it ... I will have p***ed away the entire 30 years! My life will mean sh** all! No kidding!

“I just came from speaking for 90 minutes to 4,000 of my fellow human beings, Brazilian execs and professionals and managers. That 90 minutes ... is my life. There is nothing else. Not yesterday. Not tomorrow. Only now ... a God-given, incredible, once-in-a-lifetime, never-to-be-repeated opportunity to make an impact. (Or not!) To: make a difference about some ideas I care very deeply about. (Or not!) ‘Built to last’? Who gives a tinker’s damn! Built to do my utmost to make this moment matter! To make this moment sing! Period! Tomorrow will take care of itself ... tomorrow. (If I am lucky enough to be given the gift of another day.)”

When the field of leadership and management needed a thinker, an architect, we were blessed with Peter Drucker. When we needed a “vivifier”, someone to inject animation and vitality and insightful audacity, the fates intervened, and from the bowels of McKinsey, sprang the brand “Tom Peters”, and Tom Peters the passionate human gave us brilliant food for thought packaged as performance art for just under four decades now.

We need to take inspiration from Tom Peters’ example, and ensure leadership achieves its promise, that it rattles the cages of our complacency and truly adds both value and lustre to life.