Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 17 February 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The cost of food has trended upwards, regardless of which government has been in power

By Rehana Thowfeek

A Twitter account I follow recently posted an old video of Wimal Weerawansa bellowing into a microphone at an election rally, back when he was not a part of the governing political party. In typical Wimal style, he bellows in Sinhala: “What’s the cost of rice? Of coconuts? Of vegetables? Of dried fish?”

This got me thinking, “How much are these, actually?”

Much to the people’s chagrin, Wimal is not the only politician guilty of this “What’s the cost of rice? Of coconuts?” schtick – it is a fairly common yardstick meant to measure the good/bad performance of a government in Sri Lanka, albeit a poor one.

Now you could very easily hop on over to the Census Department’s website and take a good long look at the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to get an idea of how the cost of living has gone up. This is bit complicated though; after a while, the numbers all start to look a bit like that vegetable soup Mom makes when you were sick as a kid – bland and unappetising.

So, it got me thinking; as an average Sri Lankan, what would actually help me better understand the cost of living and how it has changed over time? By some madness, surely driven by the fact I was yet to have lunch, I thought it may be useful to calculate how much a dish of food we consume regularly would cost over time.

The Big Sri Lankan Breakfast Index (BSBI)

Picking a dish was a daunting task, there are so many dishes us Sri Lankans consume regularly, but thankfully none more voraciously as the good old parippu (dhal curry). So I thought why not a Parippu

Index?

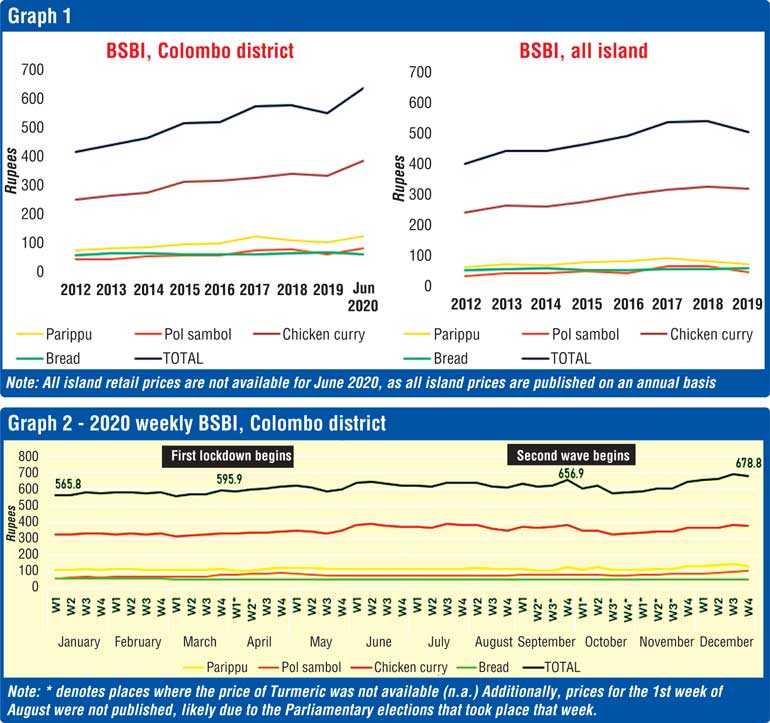

But, being typically Sri Lankan, where one curry is never enough, I thought I’ll make up the ‘Big Sri Lankan Breakfast Index’ or the BSBI – essentially, how much does it cost, for an average family of four to five people to enjoy a lip-smacking combo of parippu [dhal curry], chicken curry, pol sambol [coconut sambal] and paan [bread] for breakfast.

The BSBI recipe

I used the Department of Census and Statistics’ (DCS) annual and weekly bulletins of retail prices, which track the retail prices of a variety of food items sold in the main markets the around the country. For purposes of my sanity (if you have tried extracting data out of the DCS’s publications, you will know what I mean!), I will only use data for Colombo District (the most populated district) and the all island prices.

I have had to omit certain ingredients like fenugreek seeds, lemon grass, rampe (pandan leaf), curry leaves, chilli powder, curry powder as these are not tracked either at all or consistently by the DCS. I have also not included ingredients that are added in very small quantities (like salt, chilli powder, curry powder), nor the cost of cooking gas, nor the cost of the tuk-tuk to and from the market.

Keep in mind that the BSBI is only a measure of the cost of breakfast, and would therefore need to be adjusted accordingly to consider the cost of meals for a full day

The proof is in the parippu

Contrary to Wimal’s belief (although I don’t think he genuinely believes it), the BSBI suggests that the cost of food in Sri Lanka has trended upwards consistently – regardless of which political party has been in power. Price controls have served as little but temporary barriers from the inevitable.

In 2019, it would cost a family of four to five living in Colombo District Rs. 550 to enjoy this breakfast combo, while in 2012 it would have cost Rs. 413 – that is an annual growth rate of 4.2%. The all-island percentage increased by an annual growth rate of 3.4%. Therefore, the annual inflation on this particular basket of items remains in line with the headline inflation rates published by the DCS.

I suppose the more pertinent question for 2020 is, how does the BSBI fare in the year of the pandemic; a time where many lost their modes of earning an income?

Spotlight on 2020

The weekly bulletins available (only) for Colombo District allow us to take a closer look at the BSBI on a weekly basis for the frightful year 2020:

That is a 22% increase in the BSBI within the span of the 12 months; noteworthy considering this was a year in which many were unable to work to earn an income, or had lost jobs or taken a pay cut due to the pandemic.

Headline inflation for 2020 was said to be 4.6% by the DCS, with food inflation at 11.4% - however comparing the year-on-year prices of the 4th week of December in 2019 and 2020, the prices are Rs. 532 and Rs. 678 respectively, that is a YoY change in the BSBI of 27.6%, a vastly more significant increase than recorded by the Census Department.

Side note on gazette prices

It was interesting to note that, despite the Government announcing a cap on the prices of Mysoor dhal, tinned fish and big onions at the end of March 2020, the market prices recorded by the DCS for tinned fish was higher than the stipulated Rs. 100 per 425g tin. Only the “small seed” variety of Mysoor dhal was sold at the stipulated Rs. 65 per kilo, the medium and large seed variety were sold at higher prices.

The market prices of local variety of big onions, was “not available” except for the first two weeks of April 2020, the first which was higher than the stipulated Rs. 150 per kilo and the second which was slightly lower.

The post-breakfast lull; the BSBI in conclusion

While the DCS’s 4.6% is not a worrisome number, the BSBI’s 22% rings a few alarm bells.

Just earlier this week the Government gazetted reduced prices for 27 essential commodities, to be maintained for a period of three months. However, as we can see from the DCS’s data gathering expeditions, these ceiling prices are either not adhered at all times or a shortage is artificially created by suppliers and consumers are not able to enjoy these reduced prices.

There have already been reports of certain types of rice being unavailable in the markets since the start of the week. Gazette prices, as tweeted by MP Harsha de Silva, are not a sustainable solution to curtailing the rising cost of living felt by the general population.

Observing the graph, which plots inflation of the BSBI and the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) on a point-to-point and fixed-year basis is that;

Therefore, we can conclude that the cost of food has trended upwards, regardless of which government has been in power.

In a context of rising wages, an inflation rate of 4% is not alarming, however wages in Sri Lanka are slow to rise, especially among the informal sector of Sri Lanka who make up two-thirds of Sri Lanka’s working population. For example, after years of demand, the plantation workers were finally granted the Rs. 1,000 daily wage just a few days ago (it is also worth noting that at Rs 1,000 a day, the big Sri Lankan breakfast is probably not an affordable meal).

Like Marie Antoinette infamously said, if we can’t have bread, we can eat cake, right? Yes, we could substitute the expensive food items away and consume cheaper alternatives, but the big Sri Lankan breakfast is not luxury food; it is everyday Sri Lankan food - is it fair to expect people not to have a nice parippu, chicken curry, pol sambol and paan combo?

It is hardly surprising to see the general public lament about the rising cost of living; and politicians capitalizing on this for their benefit. Yes, prices go up, but what politicians fail to tell us is that despite all their reassurances, they hardly ever come down.

(Rehana Thowfeek is an economics researcher by profession. She blogs about topics that interest her. She has an MSc in Economics from the University of Warwick and a BSc in Mathematics and Economics from the University of London. She has worked previously for Sri Lanka-based think tanks; Verité Research and the Institute for Health Policy. At present she works for a US-based food technology company as a researcher and copywriter.)

(Link to blog: https://writtenbyreh.wordpress.com/)