Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 21 April 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

As it swept the globe starting in 1918 through the end of 1919, the deadly virus afflicted 500 million people, and left 50 million dead. Among the dead were royalty and world leaders, like Louis Botha, the first Prime Minister of South Africa, Saudi Prince Tuki I bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Rose Cleveland, a First Lady of the United States, Brazilian President Rodrigues Alves and Prince Erik of Sweden. Another notable fatality was Bavarian businessman Frederick Trump, whose grandson Donald John Trump is today President of the United States.

King Alfonso the 13th of Spain, Prime Minister Peter Fraser of New Zealand, Haile Selassie the 1st, Emperor of Ethiopia, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, German Chancellor Prince Maximillian of Baden, Queen Alexandrine of Denmark and American President Woodrow Wilson were all afflicted by the virus but recovered from their illness.

This virus was not the coronavirus that plagues us today, but the H1N1 avian virus that caused the pandemic of 1918, commonly known as the ‘Spanish Flu’. It is a strange artefact of history that while most of us are familiar with the great bubonic plagues of the 16th Century, modern society has little knowledge of the 1918 flu pandemic that infected a third of the world’s population and killed anywhere from 1% to 3% of all human life.

While the disease charged across the land and paralysed countries on both sides of the ‘Great War’, governments across the world forbid journalists from reporting the truth about its extent, censoring the press out of fear that knowledge of the pandemic would hurt the morale of troops fighting on the frontlines.

Most of the reporting about the disease came from Spain, which remained neutral during World War I, and did not censor their press’ attempts to tell the truth about the virus. In a sinister turn of events, countries from Europe to the Americas capitalised on the Spanish transparency to play down the disease’s impact in their own countries, instead taking the opportunity to brand the pandemic the “Spanish Flu”.

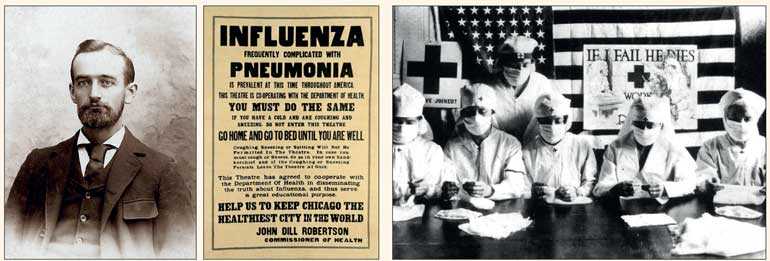

One of the few detailed modern accounts of this era is ‘The Great Influenza,’ a well-researched book by historian John M. Barry that was published in 2004. Today, experts have reached consensus that the 1918 flu originated somewhere in North America and spread rapidly across the world in large part due to the hectic pace of global activity that accompanied the first World War from 1914 to 1918. Thus, the disease that came to be known worldwide as the “Spanish flu” did not actually start in Spain. In Spain itself, the disease was blamed on the French and called the “French flu”.

Movement of soldiers

The first recorded discovery of the bug was at the US Army’s Camp Funston centre for training soldiers to fight in World War I, when an otherwise healthy army cook was suddenly diagnosed with a 104-degree Fahrenheit fever. Before the pandemic had subsided in the United States, it had killed over 670,000 Americans.

Indeed, it was the movement of soldiers from North America to Europe that exported the virus across the Atlantic. Historian James Harris wrote that “the rapid movement of soldiers around the globe was a major spreader of the disease”. Around the world, “the entire military-industrial complex of moving lots of men and material in crowded conditions” provided fertile ground for the virus to reach every corner of the globe.

As luxury cruise ships have taught us during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether they are troop carriers, aircraft carriers, passenger liners or cruise ships, boats of any kind are fertile ground for the spread of viruses over several days. A vessel that departs on a months-long journey with one infectious person can arrive at its destination with hundreds of infectious people. It was in large part due to these dynamics that the 1918 pandemic hit countries in a series of waves.

In the waning months of 1918 with the second wave engulfing the world, death rates skyrocketed. Imagine a graph of age versus fatality rate, seasonal flus usually follow a “U” shaped pattern, being deadliest to the youngest and oldest in the population. But the 1918 pandemic’s pattern followed a never before seen “W” shape, afflicting the youngest and oldest seriously, but also killing a remarkable number of people who were in their late 20s and early 30s. The millions of deaths shocked health officials worldwide.

By December 1918, Europe and the United States had largely contained the virus after two savage waves had already killed millions, but then a third wave that began in Australia made its way to Europe on a passenger liner, and then to the United States, causing a final bloody saga of fatalities before the virus finally fizzled out at the end of 1919.

Echoes of history

Exactly 100 years later we see echoes of history in how the world reacted to both pandemics; 1918’s Spain was today’s South Korea or Taiwan, being honest with their people and doing their best to plan ahead. Meanwhile, several governments around the world first played down the impact of the virus, and belatedly introduced social distancing measures and lockdowns to try and curtail the spread.

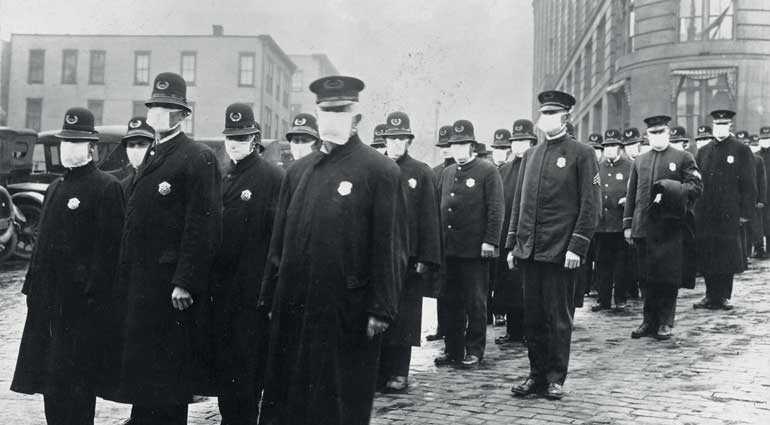

In 1918 too, social distancing was the primary tool by which states sought to control the spread of the disease. They closed schools, halted religious congregations, shuttered non-essential businesses and banned public funerals. Face masks were made mandatory and fines were imposed on people who ventured out of their homes without wearing a mask.

Our society and modern medicine have changed a lot since 1918. Overseas travel has largely migrated to airplanes. While one passenger on an airplane is less likely to infect all others onboard, a journey that lasts hours instead of months can move a virus around the world in the epidemiological blink of an eye.

Just like COVID-19, the 1918 pandemic did not spare anyone regardless of class, creed, social stature or gender. King Alfonso of Spain and several other royals around the world caught the 1918 flu, while Prince Charles of Windsor was afflicted with COVID-19. For example, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson fell ill with COVID-19 and recovered, just at the then Prime Minister of the UK, David Lloyd George survived an infection of the Spanish Flu.

Research published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases by American infectious disease specialist Dr. Karen Starko suggests that many deaths were the result of a poorly-thought-out medical decision to prescribe extremely high doses of aspirin to treat fevers, without any medical evidence that this would help patients. Patients were prescribed between eight and 31 milligrams of aspirin per day that led to blood thinning and aggravated pneumonia symptoms. Today, around four milligrams is generally considered the maximum safe dose per day.

Eerie stories

Some of the stories of how and when people got afflicted are truly eerie. President Woodrow Wilson was in Paris in April 1919, negotiating with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, about how much Germany should be punished through reparations and other measures after their surrender in World War I.

The French and British were insistent that the German people pay impossible sums of money, while Wilson objected to imposing additional hardship on war-torn Germany. One evening he fell “violently ill” with the flu, and thereafter in his weakness, relented to his allies, in a way that might have changed the course of history.

Brazilian President Rodrigues Alves was one of the most loved statesmen in early 20th Century Brazil, a professional city planner and financier who led the re-urbanisation of the capital city of Rio de Janeiro. When he was up for re-election in 1918 as the flu pandemic raged, Alves won a resounding majority, but never took office on 15 November 1918 as scheduled. Alves fell victim to the flu pandemic and died of the disease in January 2019.

Parallels between 1918 and COVID-19 pandemics

There is no shortage of parallels between the pandemic of 1918 and what we are enduring today.

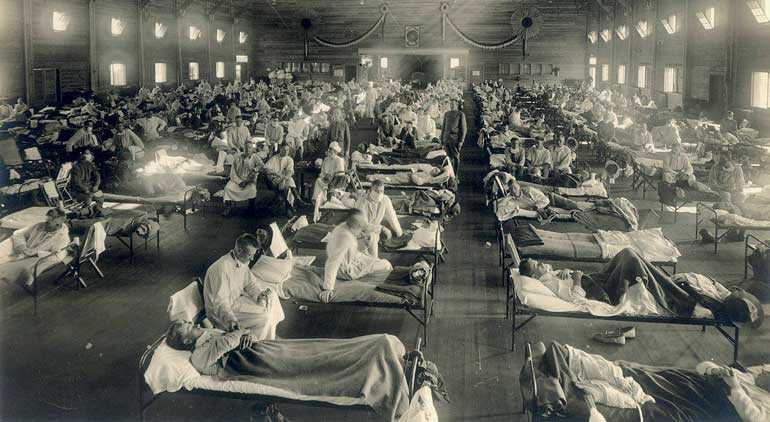

The scenes of hospitals in Italy and the United States and medical staff caring for COVID-19 patients today are reminiscent of the photographs of packed field hospitals that housed influenza patients in those countries a hundred years ago. Just as governments became complacent when their 1918 flu fatality rates declined and prematurely lifted their social distancing measures due to political considerations, some governments today are walking in those same deadly footsteps, evidenced the decision by the Governor of Florida last week to reopen public beaches in that American state.

For the world to bounce back from COVID-19, we must at least now avoid repeating the mistakes of the 1918 pandemic and take maximum advantage of the tools we have today that were absent 100 years ago. The predecessor to the World Health Organisation (WHO), known as the Health Organisation of the League of Nations, did not come into existence until 1920, well after the Spanish Flu had waned. Today, in the WHO, we have a body funded, led and staffed by people of all nations, across ideological divides, that can share advice and lessons rapidly with governments and the public at large.

Today, we have remote thermometers that allow us to check if someone has a fever without risking infection. Through electron microscopy we can see what these viruses really look like, and the fields of microbiology like virology allow us to develop treatments and vaccines. But especially when we are fighting diseases that can be spread by people who do not show any symptoms, the paradigm shift in our ability to combat a pandemic is the ability to rapidly test people for the disease, with technology that would have looked like magic in 1918.

Still vulnerable to the same follies

Despite all of these advances, we are still vulnerable to the same follies that cost so many lives 100 years ago, almost like nature is testing us to see what we have really learned as a species after so much social and technological advancement. Just as in 1918, several world leaders today tried to play down the threat of COVID-19 and were spurred to action only by public outrage caused by pointed and courageous grilling by proactive journalists who held Government officials responsible.

Nowhere is this political expedience more painfully visible today than in the United States, where President Trump seems to be oblivious to the lessons that history has learned from the disease that killed his grandfather. When he bickers with journalists on black and white matters of fact, he appears more focused on his electoral prospects than on the plight of the people he is sworn to protect.

Thankfully, in America and other countries around the world whose governments may be tempted to put their own political health over the public health, journalists and social media activists have been outspoken and insistent that today our path must be charted by health professionals who know how to keep us safe.

To be successful the world must not relive the mistakes of 1918 and be too quick to open our societies before medical professionals give the green light. When we do, we should do so taking full advantage of the medical advances we are blessed with like the ability to test people for the disease on a mass scale and identify people who have developed resistance to the COVID-19 pathogens.

Germany, which suffered severely during the 1918 pandemic, is on the road to recovery from COVID-19. It has become the first country to start a program where 3,000 households chosen at random are voluntarily tested for COVID-19 on a monthly basis for one year. This is a part of the country’s plan to thoughtfully take steps towards safely reopening their economy. Unlike the leaders of Germany 100 years ago, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, a former scientist with a doctorate in quantum chemistry, is being honest with her people and earning their trust.

We need to rethink habits. The world can replace handshakes with non-contact greetings such as the traditional Sri Lankan greeting of clasping one’s own palms together, or the Japanese bow. We must find ways to reduce the number of surfaces that are touched by large numbers of people, such as elevator buttons and door handles.

Governments must prioritise the truth

John Barry, who wrote ‘The Great Influenza’ recently opined in a New York Times article on the most critical mistake we must avoid repeating. He warns that while governments can mandate measures for their people, the most important factor is whether people will trust the advice of their governments and thus comply with what they are told. When governments lied to spin a positive picture 100 years ago, he writes, “trust in authority disintegrated, and at its core, society is based on trust. Not knowing whom or what to believe, people also lost trust in one another.”

Governments must prioritise telling the truth to their people, however bleak or politically unfortunate that truth may be at any given time. That is the only way people can have faith in their officials and feel confident in complying with their advice and directions to reign in the spread of this disease. At all costs, let us ensure that there is only ever one ‘wave’ of COVID-19.

We often think history is about the past, but one day it will be about us. In trying to research the 1918 pandemic, it becomes clear that it is not the past we are studying, but the artefacts from 100 years ago that remain intact for us today. Many generations from now, historians will write about how the world responded to and recovered from COVID-19. Each of us can play a part in influencing how this chapter in human history will be written. Let it not be one of fatalism, divided peoples and forced errors that prolonged human suffering.

Whether or not our recovery from COVID-19 will one day be remembered as one the finest moments in human history is a choice that is in our hands. Let us make this history one of when the world came together and defeated the disease restored normalcy, while harnessing the full potential of our technology and ingenuity to become more disciplined, caring and responsible stewards of our society and our planet.