Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 28 August 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

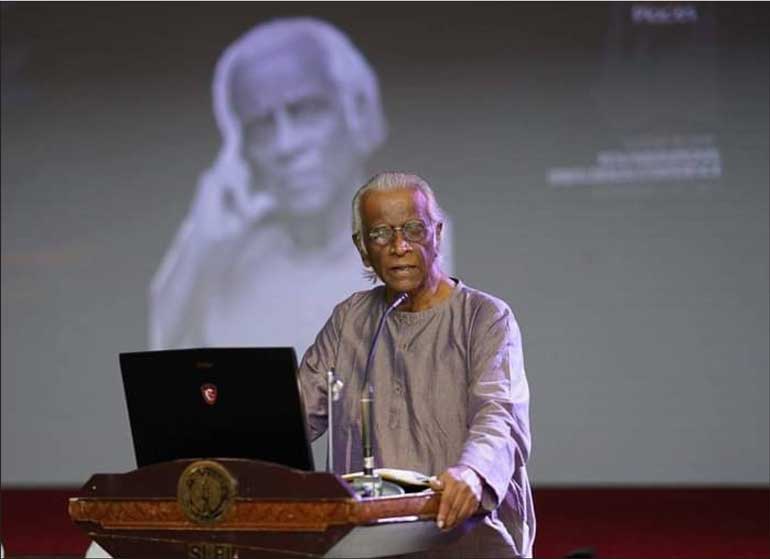

Susil Sirivardana was one of Sri Lanka’s greatest public servants

Susil Sirivardana was one of my oldest and wisest friends. He passed away on Monday morning. He chose to mentor me in public service when I was 21 years old — he’s the reason I chose to stay in the career path I picked. But he was more than a mentor. He was a friend who taught me to see a better world.

I was interning at the President’s office in early 2015. I had no designated telephone or office. I came to work one day to find out that a former Advisor to President Premadasa had left messages trying to contact me in several different offices in the Presidential Secretariat. I called him back and found out that he had read one of my policy articles on the news and had some notes for me. I went to meet him at the Housing Ministry; he shared with me his thoughts on my article and a copy of the election manifesto he had drafted for R. Premadasa in 1989.

In the next few years over many hundred cups of tea, he walked me through the policy blueprints of Janasaviya, Gam Udawa and shared many amusing stories from his unbelievable life. I will never know why he so selflessly shared all this knowledge with me, for nothing in return.

He introduced me to grassroots activists in the fight for housing for the homeless. He could have back-to-back meetings with homeless people and Presidents seamlessly. He could walk through the slums of Wekanda and into the President’s house and never change a thing about how he carried himself. “Thisuri, you need to be with the people,” he would say.

He always wanted me to remember that the real work is on the ground. That the top is where you execute policies, but the bottom is where you learn everything about good policymaking. He encouraged my reluctant, introverted self to engage grassroots leaders and learn from them.

How did a man who was raised in a comfortable home in Colombo and educated at Oxford, understand the plight of the rural poor or the urban homeless? Returning from Oxford, he took up a teaching position in a school in rural Anuradhapura. He learned to engage people and understand their stories. Spent many years there before joining the civil service.

In those early years of mentoring, while I was still an undergraduate student in America, before I had any job offers lined up in government, he encouraged me to consider taking up a teaching post in a rural school in Sri Lanka.

A year later, after joining the President’s staff, I learned from colleagues that he was calling my supervisors and senior officials at the Presidential Secretariat to complain that I was spending too much time cooped up in Colombo, requesting they send me to work on the ground with DS level officers in remote villages.

Those requests were honoured, and man did I curse his breath those first days in Monaragala. But a few days in, getting accustomed to the cold-water baths and heat rashes, I learned to come out of my shell and engage people. I learned how little I knew about the country I claim to love so much. Those were some of the most formative days in my career — I have him to thank for it.

He made me read, read, and read. His old, termite-ridden books felt apart as I read them, and were often returned to him in pieces. He quizzed me on what I had learned, and gave me even more books to read and report back; he was relentless.

My decision to continue working in government was inspired very much by him. He encouraged me to keep at it. When I was appointed to head one of the President’s policy projects when I was just 23, he was one of my biggest cheerleaders. He helped me fight my imposter syndrome.

He knew me, saw the world the way I saw it, and knew how much I struggled to work in a system that constantly stood for the opposite of what I believed in. He would call me during difficult times in the President’s office and give me much-needed words of strength and advice.

He’d say in his ever-stubborn voice, “It’s your job to do what’s right. That’s why you’ve been hired. You tell him to his face what you believe is the right thing to do. If he doesn’t listen, that’s on him. If you don’t tell him, then it’s on you. I know you can do it: be strong.”

When he found out I that I resigned during the 2018 coup, he said something that brings a smile to my face even on this saddest of days, “You make me so proud and so hopeful for the future. I always knew you had it in you. Always remember how your conscience feels right now. Never forget it.”

A big part of mentoring a young person is instilling confidence. And man did I get lucky with Susil. He took a little girl who could barely comprehend a policy paper to think bigger. Taught her the ropes and made her believe that she was good enough to write a policy manifesto. (Coincidentally, I ended up co-authoring the presidential election manifesto of Sajith Premadasa mere years after meeting Susil.)

My friends and family often found it funny that I spent so much of my time talking to this man in his eighties about public policy, but I treasured our talks so very much. In our last conversation, a few weeks ago, we spoke about the new normal, social security, and brain drain. He was upset about what the pandemic was doing to the country. I told him Sri Lanka has been through worse times and we’ll get through this one too. We ended on that note. We never spoke again — never will. I will always miss him. What an honour it has been to know him.

There are many dreams of his for this country that were left unfulfilled. I will never stop working on them. He mentored so many like me— I know I’m not alone. The world he saw is not only possible, he has laid the foundation for it.

Susil Sirivardana was one of the greatest public servants to walk the earth of my motherland. He is survived by his brainchild Janasaviya (now Samurdhi), which continues to help Lankans even after he’s gone— what an extraordinary gift.

Rest well, my friend. You will be missed.