Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 19 March 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka will soon be subject to a ban on a selection of sachets in our market. Sachet usage has been rising in Sri Lanka and other developing, low-income nations. Exponential environmental and economic impacts have been evidenced as a result of increased consumption.

Sri Lanka will soon be subject to a ban on a selection of sachets in our market. Sachet usage has been rising in Sri Lanka and other developing, low-income nations. Exponential environmental and economic impacts have been evidenced as a result of increased consumption.

The concept of a sachet dates back to the Han dynasty in China and has evolved to be a commercial mechanism to sell products in lower quantities at cheaper prices. Originally, sachets were made of cloth and wool and were carried around predominantly as scented and aromatic pouches. However, modern day sachets have become heavily commercialised to cater towards low income consumer needs.

While many products such as tea bags, medicine, herbs and spice mixes have been sold in sachets, a solitary type of sachet has emerged drastically during the past several decades. Present day sachets are predominantly made of multi-layered plastic and can be seen in almost any supermarket, fast food restaurant, coffee shops or pharmacy.

‘A Plastic Planet’ which is a movement against the use of plastic has revealed that 855 billion sachets are used every year globally by food and home care brands. Comparisons have been drawn to the number of sachets used per year, as being able to cover the entire surface of Earth. It is estimated, if sachet production continuous at current production rates without any regulation, the world will see a trillion sachets used by 2030.

Positive and negative attributes

Sachets are mostly used by low income populations and are prevalent in African, South Asian and South East Asian countries. While South East Asia is known to contribute towards half of the world’s sachet production, developing nation economies during the past 20 years have heavily become dependent on the usage of sachets.

The concept of a sachet allows for the productions of low quantities of a product at a cheaper price making it more appealing to countries in these regions. The ‘sachet economy’ promotes the consumption of small units of product and is particularly suited to consumers with limited financial resources. Consumers at the bottom of the income pyramid have inconsistent and low wages and it is economical for them to purchase small amounts rather than in bulk. This has resulted in sachet usage becoming prevalent in lower income populations.

In nations which have populations with low skill labour opportunities and where spending habits are based on low daily wage rates, sachets provide adequate comfort in providing the consumer with utilising the daily products needed in small quantities. Consumers in developing nations are price conscious, and there is extensive opportunity to capture a large segment of market share through heavily reduced pricing.

Lack of security and protection is a common issue in some impoverished areas. Residents in low income communities are unstable and they tend to have as few valuable assets on the premises as possible, therefore small quantities of single items are mostly preferred. The convenience of packaging is also considered a major advantage. Due to its size and composition, transportation has been relatively easy, enabling a wider consumer base to be reached.

The ‘sachet economy’ effectively ceases the application of economies of scale. A product purchased in bulk would be less expensive than a product purchased in smaller quantities. Although it reduces the barriers to economic participation, low-income customers pay more for such goods than their higher-income counterparts over time. This evidently results in low income populations unable to save or spend on other products which can increase individual utility.

The primary negative attribute of the sachet is its contribution to environmental degradation. Made of multi-layered plastic where polyethylene accounts for 60% in the layers, the recycling of sachets is impossible. According to waste audits which were collected during the shoreline and seabed clean-ups conducted by The Pearl Protectors, a youth led marine environment conservation organisation in Sri Lanka, sachets along with food wrappers were the leading plastic pollutants prevalent. Sachets and food wrappers account for approximately 45% of plastic waste collected. Challenges have arisen in its collection due to the sheer small sizes of discarded sachets.

Due to the multi-layering in plastic found in sachets, the prevalence of these sachets breaking into smaller particles such as microplastic and nano plastic is high. When fragmented in the ocean, microplastic are consumed by marine life mistaking plastic particle to be its diet. According to a recent study, Maldives and many of South Asia’s shorelines have the highest proportion of microplastic found compared to rest of the world.

Microplastics have been shown to damage marine organisms, as well as turtles and birds in the following ways: they obstruct digestive tracts, decrease the desire to eat, and change feeding behaviour, all of which reduce growth and reproductive performance. Globally, fish provides more than 1.5 billion people with approximately 20% of its average per capita intake of animal protein indicating the high prevalence of these microplastic ending up in human’s digestive system.

Since most of sachets are discarded through low income generating communities, the prevalence of used and discarded sachets entering the ocean through means of canals and rivers is significantly high. As many undernourished families within urban Colombo are located in close proximity to the canals, the immediate solution to many of these communities is to use the canal system to dispose of waste generated within households.

Due to the extreme price sensitivity, many undernourished households purchase the products which has the lowest prices in the market without considering the quality of product or sustainability in packaging. This vulnerability has successfully been capitalised by several large corporations where they manufacture variety of sachet brands at a significantly low price with increased distribution, effectively challenging any small or medium size companies’ ability of entrance to the market and negating space for sustainable packaging solutions.

As part of the survey conducted, views collected from grocery store vendors indicate that customers purchase sachets also for the reason to avoid content wastage. Shop owners reflected the consumers’ view where bulk purchase leads to unnecessary usage or losing the ability to control the product utilisation. This trend is prevalent where households consists of children and adolescents. This thinking process by the consumer reflects the South East Asian cultural practice called “tingi” which is a mindset of careful consumption and conscientious usage reduction.

Shop owners were also unanimously in favour of banning the usage of sachets since they bring far less benefit to the seller while also risking storage contamination where one damaged sachet could potentially contaminate other products found within the storage area and making it more tedious to identify the damaged sachet. Instead, as alternatives, the proposition of setting a bottom cap based on the weight limit for products ranging from 60ml/g to 150ml/g will ensure the consumers are provided the correct balance between price vs. quantity while allowing space for better or even sustainable product packaging.

Proposed ban

Sri Lanka’s newly-elected Government decided to ban certain plastic products during mid-2020 after the successful election campaign of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The campaign ensured that the usage of plastic was banned throughout the election campaign setting precedent to other candidate campaigns in avoiding the usage of plastic decorations.

Meanwhile during June of 2020, the coastal stretch of Mt. Lavinia saw unprecedented amounts of plastic waste gushing onto the shore prompting immediate action by the government to control the plastic waste spillage. In October 2020, the ministers of the cabinet gave the nod to a plastic ban proposal which was developed by the Central Environment Authority. The ban includes:

The ban was initially to be introduced by 1 January 2021 but was delayed due to the pressure by manufacturing companies and due to the delays in the legal sector. The proposed ban was then successfully gazetted to be implemented from 1 April 2021 onwards.

Apart from the delays, major flaws in the proposed ban were identified and are as follows;

Dilemma in the sachet ban – Survey

A survey on sachets was conducted during the early stages of 2021 to determine the characteristics of the sachets sold in Sri Lanka. Both types of sachets containing consumables and non-consumables were surveyed where the range of weight was up until 60ml/g. A significant sample amount of 64 sachets were used for the survey analysis where the purpose was to determine if the sachets are beneficial or non-beneficial towards scale of economies and to determine which sachets will be banned with the Government’s new regulations.

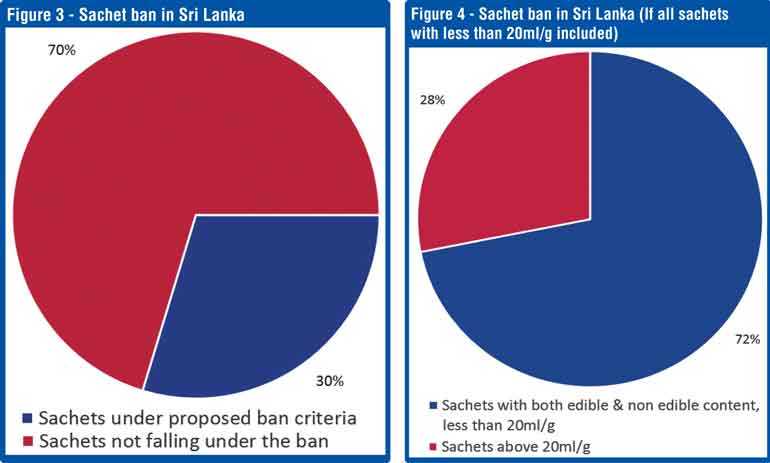

According the survey analysis, only 19 sachet brands from 64 will be banned from 1 April 2021 onwards. This is since the Government only sanctions sachets which are under 20ml/g and sachets which contains non-consumables. If the Government proposed ban is implemented, only 30% of all sachets will be removed from the market.

If the Government had instead proposed the same ban with both types of sachets containing consumables and non-consumables, which are under 20ml/g, 46 sachets out of 64 could have effectively been removed from the market. This accounts to 72% of sachets banned from Sri Lanka.

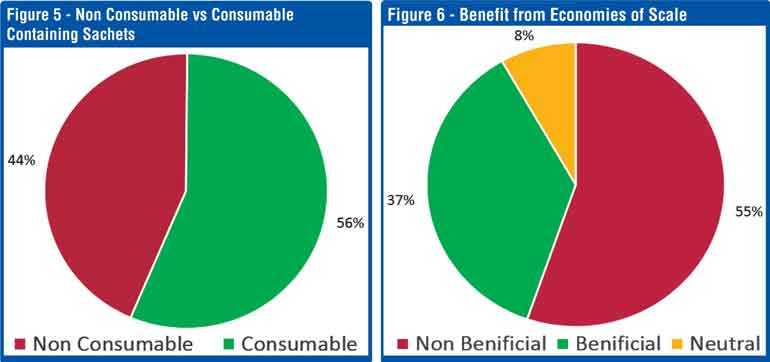

Meanwhile, 56% of sachets found in the market consisted of edible and medical products where the proposed ban will be ineffective against the majority. According to the survey, the top three sachet manufacturers in Sri Lanka are Unilever, Nestle and Hemas accounting for 45% of sachet brands available in the market.

If the Government genuinely desires to weed off the single use plastic menace from Sri Lanka, a proper timeframe mechanism is required to periodically advance in the follow-up towards banning various other plastic items without providing clauses and exceptions. The recent proposed ban as a whole prohibits only a very insignificant amount of plastic from Sri Lanka.

If the definition of a single use plastic sachet is considered to be size dimension of 144cm2 or contains equal or less than 50ml/g in weight. 91% of sachets can be removed from our markets leaving space for better packaged products while providing optimal benefits for the customer, seller and the manufacturer.

The survey also highlights how 55% of sachets are non-beneficial to the consumer in the long term. The quantity of product received for Re. 1 with sachets is far less compared to purchasing the same product at a higher quantity. This effectively hinders the saving capacity of an individual who purchases sachets on a continuous basis while also making it difficult to make a habitual improvement due to the leakage of income to purchasing sachet products.

Furthermore, 8% of sachets have equal price distributions compared to purchasing in bulk while 37% of products show an added benefit to the consumer through purchasing sachets. The reason for this price alteration can possibly be attributed due to the higher cost in non-sachet product packaging and being sold at supermarkets. The markup price of products found at supermarkets is considerably high compared to average items found at local grocery shops.

Best way out

The above survey analysis determines that the proposed ban on sachets will not have significant impact towards reducing or eliminating sachet use from Sri Lanka. To see an effective implementation of regulating the use of sachets, the primary task is to set a bottom cap on the size and the weight of plastic packaging which includes sachets.

The position paper presented to the Ministry of Environment by The Pearl Protectors highlights how setting a bottom cap can both be beneficial to the consumer and the environment. The secondary task is to eliminate the use of commercial sachet usage through a transparent process and in a timely manner. This can be achieved by introducing locally manufactured plastic alternative packaging and incentivising bulk sales. The third phrase should be to introduce a circular production phrase where packaging byproducts or discards must not enter the environment as waste, instead can be reused or upcycled.

Meanwhile, national awareness highlight needs to be emphasised towards habitual changes in product purchasing while emphasising carrying self-containers/pouches for product collection. With effective implementation, Sri Lanka has the potential to set global standards on how to phrase away from an impending global disaster due to increased sachet production.

Meanwhile, solutions of collecting used sachets have been presented throughout recent history as a possible solution to the increasing sachet waste, but history shows us how these programs have continuously failed. Unilever which producers over 40 billion sachets annually conceptualised a method called ‘Pyrolysis’ in India in 2012. This meant that sachets collected can be heated to create fuel oil and recover 60% of the energy. Heated sachet is converted from a molten state to a vapour state where the condensed vapour is stored in a storage tank. Though this process can be useful, the ineffectiveness of being able to collect the total used sachets made this method portrayed as a greenwash.

Other possible alternatives which manufactures can introduce is to establish automated vending machines where non-consumable products can be sold without packaging. Instead provide a onetime use package to the consumer where the consumer can be incentivised to reuse the container/pouch/packaging for refilling. Smaller vending machines can be introduced to grocery stores while larger machines can be installed at supermarkets.

Meanwhile the Government of Sri Lanka must consider the severity of the increasing manufacturing of sachets. With effecting regulations, incentives and awareness on sachets, equal benefits can be harnessed for the consumer, manufacturer, seller and the environment.

(The article was written by Muditha Katuwawala and the survey was conducted through The Pearl Protectors Advocacy. The author can be reached through [email protected])