Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Monday, 17 December 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Prof. H.A. de S. Gunasekara Memorial Oration 2018: Part 2

The Professor H.A. de S. Gunasekara Memorial Oration 2018 was delivered by Dr. W.A. Wijewardena on 4 December at the Senate Room of the University of Peradeniya. Today, Daily FT carries Part 2 of a revised and abridged version of the oration

The analysis so far

In the previous part, we noted that Professor H.A. de S. Gunasekara, the first Ceylonese Professor of Economics at the University of Ceylon, was a legend in economics teaching in Sri Lanka. His doctoral thesis to the University of London, ‘From Dependent Currency to Central Banking in Ceylon,’ was a seminal contribution on the development of banking, finance and central banking in colonial Ceylon.

The Five-Year Plan of 1972-76 that was produced under his direction when he was the Secretary to the Ministry of Planning and Employment sought to convert Ceylon, following the policy of the government in power, to a socialist economy. Yet, the diagnosis of economic ailments which Ceylon had been suffering at that time and the prescriptions recommended by him have not been different from what we experience in Sri Lanka today.

Thus, it was a proof that when it comes to economic analysis, both socialist economics and free market economics follow the same path. The difference is only in the end objectives. The main ailments suffered by Ceylon in the entirety of the post independence period have been the low economic growth coupled with imbalances in the budget, savings-investments and the external sector. The external sector crisis has been compounded by the low priority given to the export sector in national economic policy making.

We will examine the export sector ailments and the way forward strategy for Sri Lanka in this part.

Export-led growth policy since 1977

Despite the export-led economic growth policy program pursued by Sri Lanka since the adoption of an open economy system in 1977, the trade gap has widened creating a sizeable deficit in the current account of the balance of payments.

In this policy, the export sector was incentivised through exchange rate reforms, provision of logistical support via modernising port and airport services and introduction of a targeted export drive by inviting foreign direct investments to export processing zones. These policies enabled Sri Lanka to dramatically change its export structure.

In 1976, the export structure was heavily biased toward the three tree crops – tea, rubber and coconut – with a share of 86% in total export earnings. The industrial products had a share of only 14%. By 2017, this structure changed to 24% from agricultural exports and 75% from industrial exports. This change included a host of new export products – minor agricultural products, textiles and garments, manufactured rubber products, and machinery and mechanical appliances – which were non-existent in 1976.

Hence, there were appreciable gains by Sri Lanka after it had gone for the export led open economy policy in 1977. It indeed helped Sri Lanka to elevate from a low income country to a lower middle income country. However, when compared with its peers and from a point of continued economic prosperity, the attainments have not been sufficient.

Transformation of the export sector

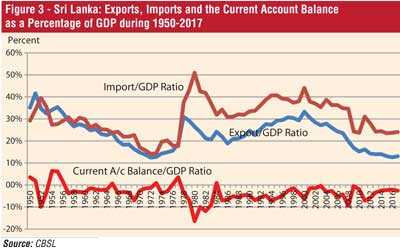

In 1951, Sri Lanka was so heavily reliant on exports that its share in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) amounted to 42%. This ratio gradually declined over the years falling to 12% by 1972. It however, increased slightly to 16% in 1976 mainly due to the slower economic growth recorded by Sri Lanka compared to the growth in exports.

After the introduction of the open economy policy in 1977, the share of exports in GDP rose to 30% in 1978, but the country could not sustain that high share since then. It gradually fell to 19% in 1986 before it started to reverse reaching a peak of 33% in 2000. After that high performance, exports began to fall once again in comparison to GDP. Finally, it fell to 13% in 2017.

Meanwhile, imports were rising both in volume and as a share of GDP, exerting pressure for Sri Lanka’s current account to record a significant deficit. It in turn affected the country’s overall balance of payments which was financed basically by resorting to external borrowings and the rupee’s ability to maintain a stable value. Accordingly, the country’s foreign borrowings which amounted to 4% of GDP in 1948 increased dramatically to 60% in 2017.

Figure 3 gives the ratios of exports, imports and current account balance to GDP during 1950 to 2017.

Exports lagging the general economic growth

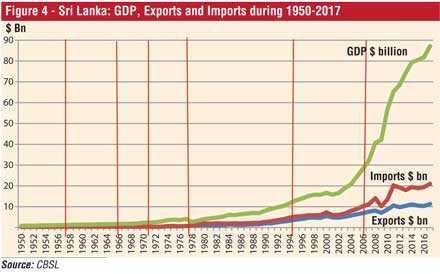

The inadequate performance of the export sector is evident from the faster growth in GDP in absolute terms compared to the absolute levels of exports and imports. Accordingly, GDP which amounted to $ 10 billion in 1993 has risen sharply to $ 87 billion in 2017, recording an eight-fold growth during the period. However, exports have risen in absolute terms more slowly. In 1993, exports amounted to $ 2.7 billion. It has increased to $ 11.4 billion in 2017, only a four-fold growth.

Figure 4 presents Sri Lanka’s GDP, Exports and Imports in absolute terms during 1950 to 2017.

Domestic economy based economic growth

The slow growth in exports has been the bane of Sri Lanka’s economic performance in the past. The faster growth in GDP than exports reveals that the economic growth has basically been attained by concentrating on domestic economy-based economic policies. They offer the advantage of allowing a country to go through adverse external shocks with minimum damage to the economy. However, they do not help a country to grow because of the limitations in the domestic market. Hence, the growth rate to be attained is slower than the potential growth as well as the growth rates achieved by peers who have got integrated to the global economy.

FT Link

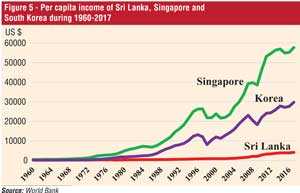

Figure 5 shows the per capita income of Sri Lanka, Singapore and South Korea during 1960-2017. All these three countries had started at the same level of per capita income in 1960.

Winners of export-led economic growth policies

However, Singapore and South Korea had adopted export-led economic growth policies since around 1970. As a result, the per capita income of both countries began to break away from that of Sri Lanka, rising to higher levels at each successive year. Both Singapore and South Korea have been able to beat successfully the middle income trap and become rich countries within a generation.

Sri Lanka’s present challenge: Beating the middle income trap

The challenge for Sri Lanka is to beat the middle income trap through a viable export development policy. This is because Sri Lanka’s domestic economy alone is not sufficient for the country to produce goods and services in volumes that would push the country up to the level of a rich country in view of the limitation of the market. Sri Lanka’s domestic market is limited by both the size and the income. It has a population of 22 million but its middle class – the segment of population that creates a demand for products – is estimated to be 3.6 million or 16% of the total population.

In comparison, USA’s middle class numbering 232 million amounts to 74% of the population. Bigger the middle class, larger the domestic market that enables a country to rely on the domestic economy based economic policies. The choice for Sri Lanka is, therefore, to adopt a strategy of selling its outputs across its borders. This is known as export-oriented economic development policies.

A classic example of how exports would facilitate a product or an industry to grow is provided by Sri Lanka’s tea sector which produces about 330 million kg of tea annually. But its domestic consumption is about 30 million kg, making it necessary for the country to seek external markets to sell the extra production. If these markets are not found, the country’s GDP will shrink by 1%, export earnings by 12% and employment by 2.5% as per data for 2017. Similarly, if the volume of tea exports can be increased by 25%, it will provide a significant boost to Sri Lanka’s economy.

Apparel sector in hot water

Sri Lanka’s main manufactured export – textiles and garments – face a major challenge due to two related developments. The textiles and garments sector benefitted from the wave of globalisation that took place in the global economy in 1980s. Accordingly, the rich countries in the world taking advantage of the low wage costs in low income countries began to set up their mass consumption product factories in the latter category of countries. This process was known as off-shoring.

However, an unintended consequence of this process was the development of the bazaar effect, as first revealed by German economist H.W. Sinn, in which the rich countries simply became trading nations – bazaars in a traditional sense – with manufacturing off-shored to low income countries. With the consequential decline in manufacturing jobs in rich countries, there was a wide public outcry against off-shoring which became a political weapon for leaders to gain popularity among the masses.

Hence, the production model was changed to locate the mass production consumption goods industries near the final markets – called near-shoring – or on the land itself – called on-shoring – through product automation. The textile and garments industry has been the first industry to exploit these new production models.

New production model to replace off-shoring by on-shoring and near-shoring

A recent survey conducted by McKinsey and Company on the apparel sectors in North America and Europe has revealed that both near-shoring and on-shoring have become the most popular production model adopted by a large segment in the final consumer countries. According to the survey, about 67% of the US apparel executives and 80% of the global chief procurement officers have indicated that the top-most priorities in the apparel sector have been the speed at which the final products should be delivered to the market and how the goods could be procured within the season.

In the past, fashions developed by apparel companies had been forced on consumers. But, that trend is fast changing and instead, a bottom-up consumer preference system in which the consumers will inform garment manufacturers to produce the fashions they desire is developing in the apparel sector. To gain capacity to produce and supply these products, apparel trading companies need to have manufacturing facilities near the markets. That is the reason for near-shoring and on-shoring to get established in the apparel sector value chain. On-shoring has been facilitated by automation of apparel manufacturing brought in by such technological advancements as 3D print manufacturing, gluing and bonding instead of stitching and robotic employment. As a result, the cost advantage enjoyed by low income countries with respect to garment manufacturing is fast eroding.

Apparel sector is to return home

McKinsey Survey has predicted that by 2025, a large segment of both the North American and European markets will be supplied by both on-shoring and near shoring. Table 1 presents the countries that are located around North America and Europe standing to benefit by adopting the new value chain model.

Will Sri Lanka lose its markets?

Both North America and Europe are Sri Lanka’s established markets for apparel products. During the 5 year period from 2013 to 2017, European Union absorbed 43% of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports, while North America absorbed 46%. Thus, these two markets had accounted for 89% of the country’s apparel exports. Accordingly, if they are to near-shore and on-shore apparel supplies, Sri Lanka’s traditional apparel industry will face a serious risk of maintaining sustainability. It is therefore necessary for Sri Lanka to change the focus of its production to new export commodities to avert possible downside development of its export sector.

In the next part, we will look at the way forward strategy for Sri Lanka.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)