Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 23 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Protectionism was the key factor that prevented Sri Lanka becoming a maritime hub 60 years ago,when our leaders could not see beyond the horizons to develop the nation in the late 50s and early 60s, which opened the doors to Singapore to be what it is today. On one hand, during this era our national unity was destroyed, and on the economic front, the pure nationalistic policieskilled entrepreneurship and investment.

The nationalisation of ports in 1958, and the nationalisation of oil companies were the biggest blunders, which took foreign companies and investment out of Sri Lanka. These were then embraced by Lee Kwan Yu of Singapore in the 1960s,who invited global giants to set up in the small island which was a strategic location in the ASEAN region, just as Sri Lanka isin the Indian subcontinent.

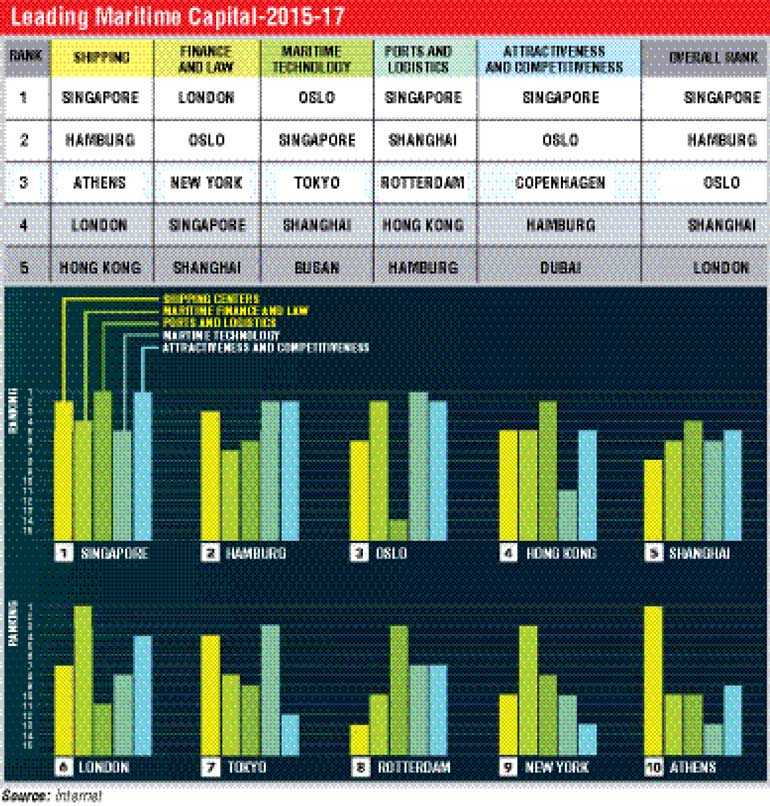

Today, Singapore is the world’s largest marine fuel and energy supplying nation, other than being number one among the ‘maritime capitals’ of the world,where Sri Lanka isnot even listed. Singapore has many refineries to provide petrochemicals, including giants such as Exxon Mobil (US) that Sri Lanka ‘sent away’ under nationalisation. This is where the transformation of Singapore took place, as it invited international companies to set up operations and build the ecosystem to make Singapore the maritime and financial hub it is today.

The same vision drives Dubai, the world’s second largest bunker supplier to the maritime industry, which created the necessary ecosystem with foreign direct investment, making Dubai the largest hub west of Sri Lanka and ranking the city in the world maritime capitals, being 5thin attractiveness and competitiveness.

Sadly, we are still stuck with the nationalised Sapugaskanda refinery, suffering fuel shortages and lack of capacity. In fact,Sri Lanka is an ideal locationwhich should have been the centre of the Indian Ocean for refinery and distribution of energy,as we have the locational advantage to be a great maritime nation.If we had invited global companies that had technology and scale,we would have been number onein such services.

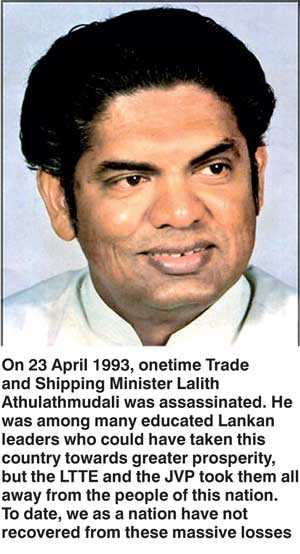

Sri Lanka banked only on “location, location, location” and ended up as atransshipment port. However, location alone is not enough in terms of developing a global business hub. Indeed,the late Lalith Athulathmudali, together with the late President J.R. Jayawardena, in 1977 saw the need for opening of the economy once again to connect Sri Lanka to the rest of the world. This economic liberalisation was probably short-lived due to the unfortunate incidents in 1983, which caused a loss of focus on the economic path.

Athulathmudali managed to develop the port and export sector to make it a transshipment hub, and this is the only area that consequent Governments managed to invest and develop. The process of public/private partnerships with greater shares given to the private sector saw Colombo Port increasing its efficiency and attracting transshipment volumes. Beyond that, Sri Lanka has failed to attract the interest of global shipping lines/logistics companies due to many reasons, including over-protectionism of cargo handling. We should aim at addressing these issues now, and at least target reforms that are needed to be a global maritime capital within a decade.

Many expected that the present Government to open the sectors for global companies to invest capital, technology& know-how to transform the country to be a logistics hub, working beyond the maritime sector. The liberalisation process was announced in 2017, but it seems slow to take off due to the lobbies and the worries of the local shipping agents that they would be wiped out due to foreign principals coming in.

I personally do not believe this is true, as existing models around the world - including Singapore and our neighbour India - have shown that when the principals are present, the local industry in fact receives more and new opportunities to provide services, and the country’s overall efficiency improves, just as clearly shown in our port sector.

Liberalisation does not mean no regulations. When liberalising, horizontal mechanisms are always there in terms of securing employment, taxation and backward integration investments. One must realise that each time a ship owner decides to call Port of Colombo, it is an indirect investment to the country, which creates business to terminals and support services. Our number one aim as a country should be to make global ship owners and logistics companies who will push government for reforms with their global experiencepart of our national business strategy. They are the people who can in the long term transform a country into a financial hub as well. We only need to create the conductive environment.

As Sri Lanka is a relatively cheaper location thanSingapore and Dubai, with an existing skilled labour force, our local companies will have greater opportunities to expand beyond agency businesses if they allow foreign companies to feel that they are part of Sri Lanka. Rather than forcing ship owners and logistics companies that own assets at global scale into the underdogposition in Sri Lanka, encouraging them to feel that they are on par with local business will be the biggest win-win situation for the country if it ever wants to be a world class logistics hub, as envisaged by the Government on its Vision 2025 plan. This progressive thinking must come from within the companies holding agencies,who should not be short-sighted at the expense of the country and their own organisations.

I write this article to commemorate the 25th death anniversary of the late Lalith Athulathmudali, who inspired me to get into the export industry in 1992. As he was a frequent visitor to my neighbourhood, I was privileged to talk to himand he always believed in an open, liberal, competitive island of Sri Lanka, capable of being a mega economic centre of the Indian Sub-Continent. I know for a fact that Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe, coming from the same J.R. Jayawardena, era has that vision, but I do worry that the local companies are truly overreacting to delay the progress of reforms our country needs. In remembering the late Lalith Athulathmudali, one of our visionary leaders lost due to terrorism, I appeal to all political leaders, business chambers and parties who are concerned with liberalisation to re-look at the sector more openly and professionally, and allow Sri Lanka to be at its proper place in the global maritime and logistics industry map.

(The writer is the CEO of Shippers’ Academy Colombo, an economics graduate from the Connecticut State University USA, and immediate past Secretary General of the Asian Shippers’ Council.)

25th death anniversary of Lalith Athulathmudali: isn’t it time to relook at our maritime and logistics industry strategy?