Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 13 March 2020 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Without the cooperation of the entire nation the spread of the virus cannot be controlled

In a previous contribution to this journal on 16 July 2019 titled ‘An Aborted University & Squandered Opportunity’ (also published two days later in Daily Financial Times), I questioned the need for a so-called ‘Sharia’ university in this country and the suitability of the site where it was being built. (I am still puzzled as to how the name ‘Sharia’ crept into the name of that university).

In a previous contribution to this journal on 16 July 2019 titled ‘An Aborted University & Squandered Opportunity’ (also published two days later in Daily Financial Times), I questioned the need for a so-called ‘Sharia’ university in this country and the suitability of the site where it was being built. (I am still puzzled as to how the name ‘Sharia’ crept into the name of that university).

Having criticised the objective behind that establishment, as an economist, I did not want an asset to be destroyed or to go waste. I therefore expressed my preference either to utilise that structure and facilities for teaching rational sciences based on the thoughts of that radical Muslim intellectual, Ekbal Ahmad, whose plan for a Khaldunian University in Pakistan was sabotaged by Benazir Bhutto and her corporate reactionaries, or, to utilise that facility more appropriately for research and post graduate studies in Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences.

The land on which it was built falls under the Mahaveli Project and ideally suited for such research activities. In the meantime, opposition to the ‘Sharia’ university was mounting from multiple directions and the Yahapalana government even appointed a committee of academics to look into the matter, but nothing came out of the committee’s recommendations. The government quietly sat on it until after the Presidential Election.

That government was thrown out, and the new government under GR also left the issue untouched until Wuhan from China provided a bizarre opportunity for an alternative use. What an alternative it is going to be!

With the fear of the coronavirus declared by WHO as a global pandemic every country is now forced to take preventive measures to control and manage its deadly impact. In some countries like Italy and China, the response has taken an extreme form by locking out an entire population of regions like Milan in Italy and Wuhan in China. Desperate times call for desperate actions.

In Sri Lanka, where the situation is largely under control, a decision by the government to pick two locations, the ‘Sharia’ University in Punani and Kandakadu Rehabilitation Centre at Sungkavil, to quarantine virus victims has provoked criticism from minority communities.

Leaving aside for a moment the legality of the government’s mode of acquiring a privately owned property, the ‘Sharia’ university, and the ethics of the investment that went into that property, let us look at the accusation against the government that it is deliberately targeting minority areas to dump the unwanted and potentially dangerous, without setting up beforehand a well-equipped epidemiological facility for treating victims.

In other words, these communities are questioning the real motive behind this decision and suspects a sinister intention of treating the minorities as disposables. Given the anti-minority sentiments prevailing already at a political level their suspicion appears to carry an element of legitimacy.

This decision of the authorities bears a parallel with another incident at the international level in 1991. In that year, the then Chief economist at the World Bank, Lawrence Summers signed a memo written by Lant Prichett on trade liberalisation in which he recommended the dumping of dirty industries or those industries producing toxic waste into the poor countries of the Third World.

Summers justified that recommendation with an economic argument in which he noted that, “a given amount of health impairing pollution should be done in the country with the lowest cost, which will be the country with the lowest wages” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Summers_memo). Hidden behind that argument was his imperialist prejudice that if the poor and the wretched were to be killed by toxic waste, not much would be lost, but more resources would become available for the rich to grab and enjoy.

That recommendation, as expected, raised a quake of criticism and condemnation from all over the developing world, which eventually forced the economist to retract from his stance. Looking at this argument in the context of Sri Lanka now, one wonders whether Lawrence Summers’ imperial prejudice is turning into an ethnic prejudice with COVID-19.

One wonders whether a regime dominated by Sinhala Buddhist supremacists, is looking at ways and means of finding a ‘final solution’ to the problem of minorities, and therefore wishing a deadly virus to do that job on their behalf. This seems to be the basis of minority suspicion, and given the recent anti-Tamil and anti-Muslim incidents how can one dismiss their fears and suspicion and call it an unnecessary over-reaction?

However, unlike we the humans, nature does not discriminate. If the virus spreads faster and kills more lives in Tamil and Muslim areas, because of the presence of ill-equipped quarantine centres, will the government then quarantine the entire population of north and east like in Milan and Wuhan? If that happens, the coronavirus would have achieved what LTTE failed to accomplish. That would be one of the most remarkable ironies in history.

Let sanity prevail

Let sanity prevail in government circles. The country urgently needs to invest in a specialist hospital, which should be fully equipped with all technical, medicinal and other facilities to handle communicable diseases and epidemics. Recently, humanity has witnessed a succession of viruses each proving deadlier than the previous ones. With hundreds of millions of people on the move daily, the speed of infection has also increased rapidly.

Almost over a million Sri Lankans are estimated to be working abroad, and who knows what bacteria or virus they will bring with them when returning home. The country has to be prepared to tackle such eventualities. Even if the current virus passes away without much damage, one is not sure when and from where the next virus will arrive and how deadlier it will be.

President GR came to office with security as the main focus of his agenda. Army, navy and the police cannot provide security to people from viruses and communicable diseases. Only cutting edge medical facilities can. Without investing on such facilities, GR’s dream of ‘prosperity with splendour’ will remain just a dream. This virus is a human and economic calamity. The economic impact of COVID-19 on Sri Lanka is yet to be revealed. Does GR have an alternative rescue package to minimise the economic impact?

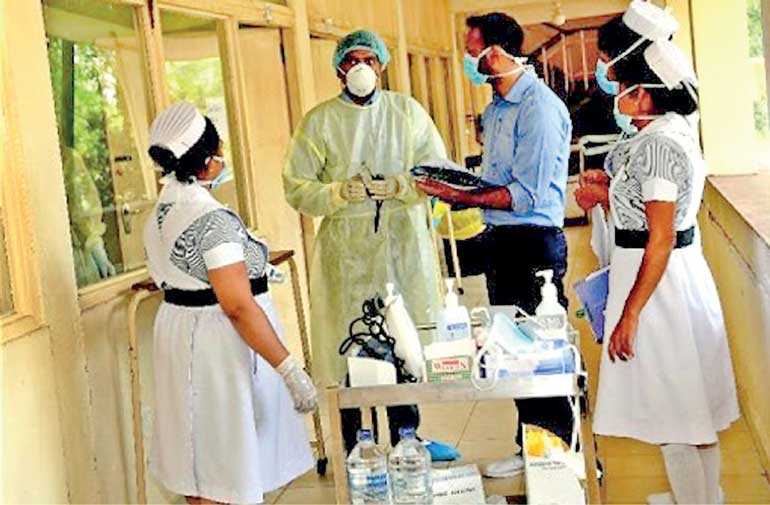

Without the cooperation of the entire nation the spread of the virus cannot be controlled. Let unwanted prejudices and hatred stand on the way of tackling a universal pestilence.

This brings us back to the issue of post-war reconciliation with and peace dividend extended to minorities. This national question, if continues to remain unresolved will debunk all good intentions and development efforts of GR and his government. Sooner they realise this fact and make some hard political decisions better for the country and its future. This is the best opportunity to do that.

(The writer is attached to the School of Business and Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia.)