Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 9 June 2018 00:14 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Bangladesh had gone through military rule between 1975 and 1990, but today it is seen as a vibrant (and turbulent) democracy.

However, Western observers have been harping on a marked and persistent “democracy deficit”, viewing the South Asian country through Western concerns and suggesting solutions with those concerns in mind. Bangladeshi commentators, on the other hand, see the same phenomena from a different angle and suggest a different set of solutions.

In the latest “Democracy Index”, using Western criteria, Bangladesh is ranked 80 out of the 129 countries reviewed. It shares the 80th place with crime ridden and oligarchic Russia. This is not a flattering image.

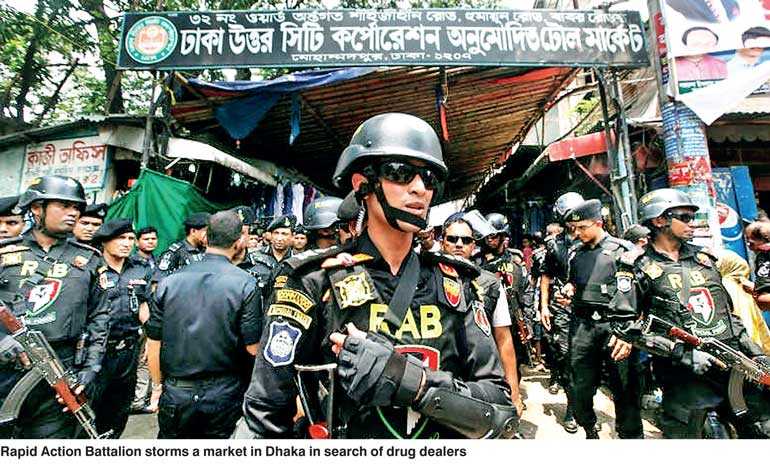

The latest controversy to be highlighted is over the ongoing “war against drug lords and traffickers”. About 130 people have been killed in the past three weeks and 9,000 arrested and 12,000 prosecuted in an unprecedented armed campaign against drug traffickers.

As the death toll mounts, objections have been raised against the “extrajudicial killings” of the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), which is accused of wearing three different hats – that of judge, jury and executioner. There are also charges that the operations are directed against opponents of the Sheikh Hasina regime, principally, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) headed by rival Begum Khaleda Zia.

Though drug offences invite the death penalty in many countries and there is a worldwide campaign against drug trafficking and its links to terrorism, including the dreaded Islamic terrorism, Western rights activists are alarmed that Bangladesh is planning to impose the death penalty on drug kingpins, with 32 ministries recommending.

Condemning the current spate of “extra judicial executions” of drug traffickers, US Ambassador to Bangladesh, Marcia Bernicat, said: “Of course I express concern about the number of people dying. Everyone in a democracy has a right to due process.”

International rights campaigners have declared that the Bangladeshi authorities are “seriously misguided” if they think they can tackle drug crime by committing even more violent, illegal acts. According to them, Bangladesh needs to carry out operations respecting human rights, the Rule of Law and due process.

International rights campaigners have declared that the Bangladeshi authorities are “seriously misguided” if they think they can tackle drug crime by committing even more violent, illegal acts. According to them, Bangladesh needs to carry out operations respecting human rights, the Rule of Law and due process.

Raising apprehensions about a political objective in the ongoing anti-drug campaign is the alleged attempt by the Hasina regime to weaken the opposition BNP by cracking down on its leader Begum Khaleda Zia. In February this year, Khaleda was sentenced to five years’ Rigorous Imprisonment for embezzling funds of the Zia Orphanage. Khaleda’s son and political heir, Tarique Zia, who lives in London, was sentenced in absentia.

The sentencing of the mother and son has rendered the main opposition party leaderless with only five months to go for the next parliamentary elections. Rights workers see such trials and sentences as politically motivated and unwarranted, overlooking the fact that South Asian politicians indulge in high corruption but rarely get punished for it thus setting a bad example to others. Few would acknowledge that there could be a genuine case against Begum Zia and her son, and that it can be decided only by a court of law.

Strong action has been the hallmark of Prime Minister Hasina’s regime since it was installed in 2008. Last year, after a group of young upper class Jehadists brutally killed tourists in an up-market restaurant in Dhaka, Hasina had gone hammer and tongs at Islamic terrorists, ruthlessly eliminating them in “encounters”.

Prior to that, Hasina had set up special tribunals to try those who committed crimes against Bengalis in the 1971 war of liberation. International human rights organisations cried foul as many were sent to the gallows forgetting the horrendous nature of the crimes committed.

While rights bodies funded by the West cried foul against all her strong actions, Hasina felt that she had every reason to be harsh on the forces ranged against Bangladesh. It was for the good of Bangladesh that those who committed “war crimes”; who joined Islamic terrorists with global links; and who became drug traffickers had to be put down ruthlessly. Former Prime Minister Begum Zia had to be jailed for corruption to show that the law does not discriminate between the hoi polloi and the political elite.

Drug menace is immense

The use of Methamphetamine (called Meth or Yaba, a cheap and highly addictive drug) is widespread in Bangladesh. 70% of Yaba pills come from in western Myanmar. The drug is synthesised from pseudoephedrine and caffeine, which are smuggled from India, China and Vietnam.

There are seven million drug addicts in Bangladesh, five million of whom are hooked on Yaba; 63% of the addicts are in the age group 15 to 25. A study by Manas reveals that minors under 16 account for 25% of drug addicts. The addiction has spread from cities to deep into villages. A recent report also said that one out of every 17 youths is addicted.

A 2013 study found that people were spending Tk.200 million ($ 2.3 million) daily on drugs. Drug addiction has led to dropping out of educational institutions.

Courts and jails are inundated by drug cases. In 2017 alone, 98,984 narcotics related cases were filed. The total number of pending cases in 2017 was 213,529. Drug cases were 46% of all cases filed in 2017. As of 19 March this year, 35.97% of prisoners are in on drug related charges. Drugs continue to be taken in jails with the connivance of jail officials.

Prof. Zia Rahman, Chair of the Department of Criminology in Dhaka University, has said that the government needs to return addicts to the country’s pool of human resources through psychiatric treatment. Punitive action alone would not help.

Mekhala Sarkar, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the Department of National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), has said that if an addicted person gets proper treatment, chances of that person becoming addicted to drugs again drop significantly. Studies have shown that for every US dollar spent, good prevention programs can save governments up to $ 10 in subsequent costs.

Reasons for addiction

Excess money in the hands of the Bangladeshi upper class youth due to rapid economic growth, and increasing poverty and joblessness among the youth of the poorer classes, have led to drug abuse ,says left oriented political commentator Afsan Chowdhury. “Bangladesh has seen economic growth but this has been jobless growth,” he observed.

According to International Republican Institute (IRI), despite a growing economy, Bangladeshis complain of high unemployment, rising prices, and various other economic challenges. They also say bribes and other forms of corruption limit access to jobs, rule of law, healthcare, education, and other public facilities. All these have led to frustration and drug addiction. Massive smuggling from Myanmar is adding to the problem.

“The people by and large approve of the strong actions taken by the Hasina government because those harshly dealt with are seen as criminals who deserve what they get. But the real problem lies in poor governance and the faulty functioning of the organs of the State,” Chowdhury pointed out.

“The remedy is in making corrections to the functioning of governmental systems including the elected bodies, the police, the bureaucracy and the judiciary. The root of the problem is governance deficit and that has to be addressed if there is to a lasting solution to the issues confronting the country,” he asserted.

He stressed the need for a bipartisan approach because the State has behaved in the same way irrespective of the party in power.

As regards the jailing of opposition leader Khaleda Zia, Chowdhury said that it is a judicial matter and has to be settled by the court. But he felt that applying undue pressure on her and the BNP will only alienate the voters and deliver sympathy votes to the BNP in the next elections due at the end of the year.

“The BNP, which is inherently weak, being an urban-based middle class party with few cadres (unlike Hasina’s Awami League), may gain adherents if Hasina is seen as being vindictive,” Chowdhury warned.

The West’s diagnosis of the problem in Bangladesh is not correct and its solutions will not work, he felt.

“The root of the problem is in the faulty functioning of State institutions, class discrimination, corruption and jobless economic growth leading to inequalities,” Chowdhury said.