Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Thursday, 1 July 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

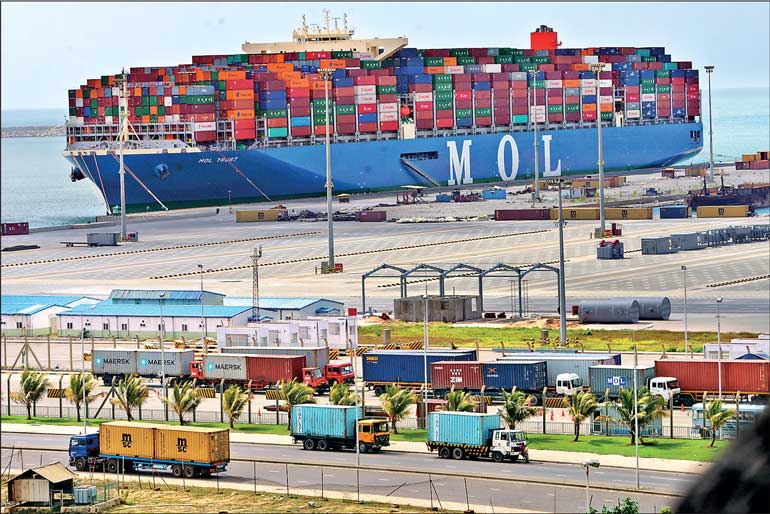

Perhaps the best way to understand how the missed opportunities in global production sharing dictated Sri Lanka’s lopsided export performance is to compare the Sri Lankan export record with that of Vietnam, a latecomer to export-led industrialisation that has already shown promising signs of growing by joining GMVCs – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Missed opportunities and prospects

Missed opportunities and prospects

As noted, the heavy concentration of the export composition in garments has been a major concern in the Sri Lankan policy circles. However, the important issues of why the export success in garment industry did not take place in other industries as in the export-oriented economies in East Asia has not received due attention in this debate.

A comparison of Sri Lankan export composition with that of the high performing East Asian Economies (HPEAEs) vividly indicates that this lopsided nature of the export structure reflect Sri Lanka’s missed opportunity to engage in ‘production sharing’ within vertically integrated global industries such as data-processing machines, telecommunication and sound recording equipment, electrical machinery and appliances, and professional and scientific equipment (broadly labelled as electronics and electrical industries).

Global production sharing – cross-border dispersion of manufacturing processes that opens opportunities for countries to participate in different stages of the production process of a given product – has been the prime mover of shifting manufacturing production in these industries from mature industrial countries to developing countries. This phenomenon opens up opportunities for countries to engage in specific segment in the global manufacturing value chain (GMVC) depending on their relative cost advantage, intend of producing a good from the beginning to end within its national boundaries. The bulk of manufacturing exports from the HPEAEs, over two thirds of exports in some of these countries, take place within GMVCs (Athukorala 2014a).

In garments and other standard defused-technology industries, local entrepreneurs in a given country have the opportunity to penetrate global markets through links forged with international byers, with or without FDI involvement manufacturing, depending of course if the other preconditions are satisfied (as in the case of Sri Lankan garment industry). However, in GMVCs in electronics and electrical industries, production sharing takes place through intra-firm linkages, rather than in an arms-length manner. Intra-firm linkages are vital for preserving technological secrecy and/or to ensure quality/precision of parts and components produced in a given location, which is vital to maintain quality standards of the final product. Therefore, FDI plays a vital role in a country’s participation in GMVCs in these industries.

The investment promotion campaign of the Greater Colombo Economic Commission (GCEC, later renamed the Board of Investment, BOI) placed emphasis during the early stage at attracting FDI into electronics and electrical assembly. In fact, the GCEC was successful in bringing two major electronics multinationals, Motorola and Harris Corporation, to the Katunayake Export Processing Zone (KEPZ).

Motorola registered a fully-owned subsidiary in October 1980 to establish an assembly plant with an initial employment capacity of 2,624 workers. Motorola’s decision to come to Sri Lanka was motivated by Sri Lanka’s incentive package and perceived political stability of the country at the time, which handsomely compensated for the inherent locational disadvantage (long distance from the USA) (Weigand 1983). (On signing the investment agreement with the Greater Colombo Economic Commission in 1980, W.D. Douglas, a Vice-President of Motorola, stated: ‘Political stability is number one on our list wherever we go,’ quoted in Wijesinghe (1976)). Harris Corporation registered a fully-owned subsidiary and even started building a plant in KEPZ with an initial employment capacity of 1,850 workers. Motorola left Sri Lanka in 1983 flowed by Harris Corporation in 1984 to locations in Malaysia as the political climate begun to deteriorate in Sri Lanka. As of 2013, Motorola plant in Penang was employing 6,500 workers; Motorola’s operations in Penang has spawned a sizeable cluster of local subcontracting firms, some of which have become independent companies with even foreign operations on their own (Athukorala 2004b).

There is evidence of a “herd mentality” in site selection by multinational electronics firms, if the “first-comer” is a major player in the industry. If the Motorola and Harris Corporation projects had succeeded, other multinationals would have followed suit (Snodgrass 2008). Moreover, the entry of large players in vertically integrated global industries naturally sets the stage for the emergence of local small and medium scale firms supplying ancillary components and services, as in the case of Motorola’s operation in Penang (Athukorala 2014b).

Perhaps the best way to understand how the missed opportunities in global production sharing dictated Sri Lanka’s lopsided export performance is to compare the Sri Lankan export record with that of Vietnam, a latecomer to export-led industrialisation that has already shown promising signs of growing by joining GMVCs.

Vietnam embarked on market oriented reforms (transition from ‘plan to market’) much later than Sri Lanka (in the late 1980s). Since then until about the mid-1980s, Vietnam’s export volume (in US$) was smaller than that of Sri Lanka. In 2005-06, when the export volume was more or less similar between the two countries, garments accounted for the lion’s share of exports (nearly two thirds) in both countries. Since then, Vietnam has made a notable departure from Sri Lanka in export performance. By the end of 2010s, Vietnam accounted for over 5% of manufacturing exports from developing countries compared to a mere 0.13% share of Sri Lanka. Vietnam’s meteoric rise as a dynamic export has been underpinned by a notable shift in the commodity composition towards dynamic products within GMVC, in particular electronics and electrical goods. In 1918-’19 garments accounted for just 13% of total manufacturing exports from Vietnam. This process of dramatic structural transformation in Vietnam gathered momentum following the arrival of Intel Corporation in 2006 to set up an assembly and testing plant in Ho Chi Ming City (Athukorala and Kien 2020).

Mini electronics boom

Even though large electronics MNEs shunned Sri Lanka because of the country risk, a sizeable number (over 30, according to BOI records) of fully export-oriented medium scale FIEs have been successfully operating in electronics, electrical goods, and auto part industries in the country for many years now. These firms currently employ over 20,000 workers (SLEDB 2014).

These firms produce (mostly assemble) a wide range of parts and components ranging from sensors for the Airbus and weighing components for baby incubators. Total exports of these products increased from $ 247 million (6.1% of total manufacturing exports) in 2007-’08 to $ 958 million (10.3% of total manufacturing exports) in 2018-’19. The annual growth rate of exports has been much rapid in more recent years: average annual growth rate of over 15% during 2015-2019 compared 9% during 2007-2015. These are the fastest growing group of products in Sri Lanka’s export composition during this period.

Surprisingly this important development, which is relevant for any discussion of the country’s export future, remain obscured in the Sri Lankan trade policy documents and policy debate. In the Central Bank Annual Report, these dynamic product remain hidden in various sub categories under the broader category of machinery and transport equipment (Table 81 in the 2020 Annual Report)

We have put together as part of our on-going research basic information for 13 companies through internet search and interviews conducted with company executives. All these firms are FIEs, with full or partial foreign ownership. The foreign parent companies of these FIEs are ‘Nano’ multinational enterprises (NMNEs) with operations in a few countries. They specialise in specific parts and component production and assembly within GMVCs through close, but alms’ length, relations with original-manufacturing MNEs or large contract manufactures (CMs). Japan is by far the largest home country of these investors.

These investors have come to Sri Lanka based on personal contacts in the Sri Lankan business community, rather than in response to the investment promotion campaign of the BOI. All executives we interviewed stated that a trusted local relationship acts as a cushion against political risk and help attending with ease administrative commitments to various Government bodies.

The owner-manager of a highly successful auto part making company has written that, ‘For decades, the Sri Lankan Government through the BOI has embarked on many investment promotion missions to Japan and other countries. The writer participated in two such investment promotion missions to Japan in 2007 and 2013. These investment promotions impose a heavy financial burden on the national coffers. But the fact is that the BOI has failed to attract even a single substantial Japanese investor since the last Japanese investor came to Sri Lanka in 2002 that too on the initiative of the writer, not as a result of BOI promotion missions. Easjay Electromag, Tos Lanka, Laka Harness, Areosense, Cable Solutions, Metal Component Services, Lanka Precision Works, Nipon Maruchi were all established in Sri Lanka through a strong local relationship that was trusted by the foreign investor ...’. Pallewatta (2018, p 245)

Availability of trainable labour and complementary supervisory manpower is the major attraction of Sri Lanka as a production location for these investors. Contrary to the popular perception among policymakers in the country, none of the executives we interviewed complain about a human capital constraint. The majority of firms are in the hands of local managers and all workers and supervisors have been trained on the job within the firm. Some firms send their new recruits to their home countries for training.

We found no evidence to suggest that the advent of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution (IR4) would put an end to the type of activities undertaken by these firms. In principle, almost all production processes can be robotised or automated, but, in reality, the actual replacement of labour with this IR4 technology depend on the relative cost of doing so, which depends on both complexity of the production process and the bulkiness of the given product. Automation or robotisation does not seem to be a cost effective alternative for the human touch involved in intricate assembly processes undertaken by these firms.

According to our firm-level surveys, the Sri Lankan firms involved in assembling weighing cells, auto wire harnesses, sensors for aircrafts and optical insulators have long-term plans to expand production. Recently UK-based major player in the global aircraft component industry bought a Sri Lankan US-Sweden-UK joint venture firm producing sensors for Airbus as part of its production expansion program. The new owner has plans to expand the Sri Lankan operation to a projected employment capacity of 2,000 workers, up from the current employment of 60 workers.

Concluding remarks

Concluding remarks

The backlash against liberalisation reforms in the contemporary Sri Lankan policy debate is largely based on defunct ideological predilection rather than factual analysis. The comparative analysis of Sri Lanka’s industrialisation experience during the State-led import-substitution era and that of the post-reform era (in particular during the first two decades) in this paper makes a strong case for reconsidering the merit of the emerging emphasis on combining import substitution and export orientation with a State-guided sector specific focus. Selective policies to promote import substitution essentially impose a ‘tax’ on export producers.

The economic liberalisation reforms initiated in 1977 have brought about far-reaching changes in the structure and performance of the Sri Lankan manufacturing sector. The reforms helped transform the classical export economy of Sri Lanka inherited from the colonial era into a one in which manufacturing plays a significant role. The achievements of liberalisation reforms are all the more remarkable when we allow for the fact the proposed reform package was not fully implemented and that the country failed to capture the full benefits of reforms undertaken because of the protracted civil war that damaged the investment climate and undermined macroeconomic stability.

The experience under liberalisation reforms demonstrated the complementarity of trade and investment liberalisation in the process of export-oriented industrialisation: trade liberalisation increased the potential returns to investment by capitalising on the country’s comparative advantage, while liberalisation of foreign investments permitted international firms to take advantage of such profit opportunities. There is compelling evidence that the entry of foreign firms is vital for a “latecomer” to export successfully. In addition to foreign-invested enterprises’ direct contribution to export expansion, their positive spillovers have contributed to the success of local exporting firms.

The Sri Lankan garment industry has successfully consolidated its position as a dynamic player in a highly-competitive global market in the post-MFA era, contrary to the popular perception that treat it as a traditional sunset industry. Sri Lanka missed the opportunity to gain export dynamism by entering into global manufacturing value chains in vertically integrated electronics and other related industries because of the debilitating country risk caused by the civil war and policy uncertainty. However, a small but dynamic parts and component industry has emerged during that period through trustworthy personal links between international investors and the Sri Lankan business community. There are indications that this industry has the potential to become the harbinger of export dynamism in the post-civil war era, depending of course on the country’s commitment to continue with reforms to facilitate global integration of domestic manufacturing.

Trade-cum-investment policy reforms has the potential to set the stage for new exporting industries and exporting firms to emerge in a global context in which factors of production―capital, technology, and marketing and managerial knowhow––are mobile across national boundaries. Developing the human capital base and building the country’s innovative capabilities should of course be among the Government’s long-term policy priorities, but there is no need to wait to achieve these objectives in order to link domestic manufacturing into global production networks. The human capital constraint on export success is vastly exaggerated in the Sri Lankan policy debate.

When talking about sector/industry specific approach to industrialisation, we should not forget the fact the Post-World War II economic history of developing countries, including that of Sri Lanka, is littered with cases of costly failure. Or course there were a few seemingly successful cases in some countries, but the available evidence clearly supports the view that these ‘successes’ were rooted in three fundamental traits of the industrialisation policy regimes of these countries. First, the incentives given to the specific industries were strictly time bound; second, export performance requirement was strictly imposed on the beneficiary firms; and thirdly selective intervention was undertaken in the context of an overall economic setting that was conducive for private sector operations.

It is pertinent to quote here the founding father of the Korean economic miracle: ‘The economic planning or long-range development programme must not be allowed to stifle creativity or spontaneity of private enterprises. We should utilise to the maximum extent the merit usually introduced by the price mechanism of free competition, thus avoiding the possible damages accompanying a monopoly system. There can be and will be no economic planning for the sake of planning itself’ Park (1970, p. 214). (Park Chun He even has a prison (Seodaemun) near his palace to lock up businessmen whose did not adhere to his directives!)

Selecting a large number of industries for preferential treatment and promising to add even more (CBSL 2021, p. 20) is a recipe for strengthening the hands of the domestic lobby that clamour for trade protection and Government support. The known successful cases of selective intervention world over were based on selecting a few cases based on systematic assessment of world market conditions and potential for gaining dynamic comparative advantage within an overall economic environment that is conducive for unhindered private sector operation. If there is uncertainty, the best practice has been to rely on market forces.

To quote Lee Kuan Yew: ‘We left most of the picking of winners to the MNEs that brought them to Singapore. A few such as ship repairing, oil refining and petrochemicals banking and finances were picked by the EDB or Sui Sen, our minister of finance or myself personally… When we were unsure how new research and development would turn out, we spread our bet. Our job was to plan the broad economic objectives and target periods within which to achieve them (Lee, 2000, p.85).

In sum, the analysis of regime shifts and economic performance under State-led import substitution strategy and liberalisation reforms in this paper makes a strong case for averting backsliding in policy, continuing the market-oriented reforms agenda that was left incomplete in the late 1990s, and setting up institutional safeguards to avert further policy backsliding.

(The full paper, with figures, tables and references, is available at https://acde.crawford.anu.edu.au/publication/working-papers-trade-and-development)

(The writer is attached to the Arndt-Corden Department of Economics, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University and can be reached via [email protected])