Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 3 November 2020 00:16 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

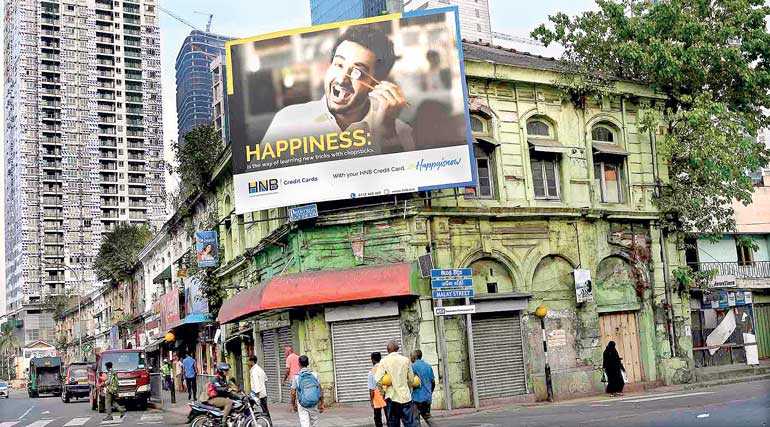

In a fast-changing world of rising inequality, climate change and volatility, humanity needs to rethink what ‘development’ means – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The world has changed significantly since COVID-19 hit humanity less than a year ago. This virus has brought human activity as we knew it pre-COVID-19 to a halt and shown no respect for race, religion, wealth, social status or geographical location. In fact, global statistics have shown that infection and fatality rates have been higher in the ‘developed’ countries in North America and Western Europe, than in the ‘developing’ countries of Asia and Africa.

I believe that the most important quality in life is contentment. If one accepts that premise, whichever the country and whatever its state of ‘development,’ the COVID-19 pandemic has had a strong impact on our lives. It has made people realise that only a few things in life really matter – interaction with families and friends, nutrition, physical and mental health and hygiene, and a clean and safe living environment.

These essential human needs can be translated into three simple pillars of emotional, intellectual and material well-being. Life under COVID-19 has made it clear that most other ‘needs’ are actually ‘wants’. These wants are not really essential for our overall wellbeing, but fuelled by strategic marketing over decades in a global environment of rampant rising consumption.

Measures of ‘development’

Going back 70 years in history to the end of the last world war (WWII), the planet held a population of 2.5 billion people, abundant plant and animal life, water resources and fossil fuels. Simply put, the need at that time was to maintain international peace and security and rebuild the world, more specifically the Western world, destroyed by war.

In that historical context, global institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were created to achieve these objectives and to fund and stabilise nations and their currencies towards this end. From that initial need, an economic model was developed to promote consumption.

The new economic model would encourage factors of production—land, labour and capital—to produce goods and services that would rebuild those countries from the destruction of WWII. That model worked well for some time, improving for many, their access to basic needs such as food, clothing, housing, education and health services.

Then, measures of ‘development’ were entirely economic, focussed on the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services. Gross domestic product (GDP), GDP growth, GDP per capita, consumption, investment and savings were the key indicators used to measure a country’s ‘development’ over time and relative to other countries.

Individual ‘development’ was also measured in terms of ownership of money and physical assets. Seventy years on, ‘success’ has become even more tied to money and what it can buy – houses, cars, clothes, i.e. material well-being, and even people, positions and fame.

The pursuit of intellectual well-being, education and employment, also became tied to money, i.e. education for employment that would provide higher incomes to purchase and consume more. Emotional well-being was neglected in the pursuit of money and all it could buy. While money is necessary for our survival, it cannot buy contentment.

A ‘development’ model that encouraged consumption may have served well for a time in a world where the human population was low relative to natural resources. Yet 70 years later, on a planet now holding over 7.5 billion people, with greatly depleted natural resources slowly but surely being destroyed by human ‘wants,’ that model has long reached its used-by date.

Meanwhile, financial markets, initially established to facilitate the production and distribution of goods and services, began to take a life of their own. Today’s values of financial instruments and businesses, with prices based on market sentiment and speculation, are no longer necessarily directly backed by real assets, real performance or reality. ‘Bubbles’ have been created, which have, and will continue to, burst anytime.

Humanity needs to rethink what ‘development’ means

In a fast-changing world of rising inequality, climate change and volatility, humanity needs to rethink what ‘development’ means. Publications of international organisations—UNDP Human Development Report (since 1990), World Development Report (since 1978)—record that development indicators, mainly measured income-related material well-being in the past. They have since been replaced by indicators of overall human well-being such as the Human Development Index (HDI), which measures GDP, life expectancy and education.

Other more recent measures cover Gender Equality, Law and Order, Governance, Corruption and Happiness, to name a few. These changes recognise that material well-being, alone, does not bring contentment, peace and security and that environmental sustainability is essential for life on our planet to continue. The current concept of ‘Sustainable Development’ includes all three pillars of human well-being and advocates simplistic, but relevant ‘Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’ for nations to aspire to.

Yet, old habits and constant brainwashing cannot be so easily erased. The mindset in many parts of the world unthinkingly continues to aspire to the goals of that Western-dominated Post-WWII consumption model. However, our planet cannot sustain it. Also, while higher material well-being could lead to greater intellectual and emotional well-being up to a certain level, beyond that, it does not ensure a better overall quality of life.

There is really no rationality in aspiring to endless wealth

In our pre-COVID-19 world, with rising income disparities, there was great hardship at the lower end of the income pyramid, with poor access to housing, nutrition, health and education. At the middle level, incomes could not meet aspirations driven by consumption-led ‘development’ successfully marketed globally through technological connectivity.

At the upper end, money, which can only be used to make more money or consume more, had lost its value beyond a certain threshold. Think of high net worth individuals, of billionaires, of stocks and shares sky-rocketing in certain companies, that we read and hear about. In essence, the excess monies and the oft-accompanying fanfare become meaningless to those very individuals and businesses that make the most.

With only one physical body and one set of the five senses, one can only be in one location, stationary or in motion, in one outfit, savouring one dish or feasting on one work of art at any given moment. Thus, unless an individual is to be forever discontented, however many his houses, vehicles, clothes or art works, his marginal utility of an added unit of consumption at that level of affluence will be negligible.

I commended a globally-recognised retired billionaire entrepreneur who was trying to ‘make a difference’ with his wealth to help the less fortunate, to my son. He responded wisely, “Better if he had paid his employees more throughout.” There is really no rationality in aspiring to endless wealth.

A new ‘development’ model

In today’s globalised COVID-19 world, the global economy as we know it is in lockdown. At both national and international levels, most income-generating activities are virtually at a standstill. Many individuals, businesses and governments are unable to meet their financial commitments. Banking and financial institutions, domestically and internationally, are facing new challenges on their portfolios.

At individual level, there is great hardship without employment and income at the lower end of the income pyramid. Incomes are down at the middle. At the upper end, money is of little use, with consumption of goods and services, especially travel, limited during a lockdown.

Yet, much of humanity who were trapped in a consumption-driven pre-COVID world, are rediscovering simple pleasures of human interaction in the enforced lockdown. One hears of families reconnecting and of neighbourhood communities reaching out and helping each other. Individuals are finding time to read, to learn new skills, to reconnect with friends across the globe (thank goodness for technology and global connectivity), and most importantly, to reflect and reassess life’s priorities. The COVID-19 world war has forced humanity to realise that a new ‘development’ model has to be found to meet our planet’s needs in the 21st century. Humans have to replace overt consumption with realistic use and re-use of available, but depleting resources and prioritise a more holistic concept of human well-being. Money, finances and business value have to be reinvented; global and domestic debt and debt repayments have to be rethought; new business models of reduced profits and higher employees’ wages need to be considered.

If all three pillars of human well-being are important, a new global ‘development’ model should prioritise two interconnected goals—improving overall human well-being while preserving the natural environment.

It is because nations cooperated and collaborated and built international institutions post WWII to meet common needs and help each other that they were able to rebuild a broken world. 70 years on, will geopolitics and humanity’s greed and arrogance allow us to recognise that we are off-track? Will we ever see that we need each other, individuals, communities and nations, to share knowledge, skills, experiences and efforts to save ourselves and what is left of our planet for future generations?

(The author is a former Assistant Governor and Director of Statistics of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)