Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 7 April 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Violence appears to be contagious. It is like a horrible epidemic like COVID-19. The insurrection changed the mindset of many people, alas negatively, both in authority and those who almost naturally opposed it, and on both sides of the ethnic divide. The reasons for the distinctions are not easy to figure. The insurrection opened the floodgates and Sri Lanka never could become the same

Fifty years ago, 5 April 1971, was a Monday. I was an assistant lecturer in economics at Vidyodaya University during that time, a prominent stronghold of the JVP (People’s Liberation Front), which led the insurrection. When I went for my lectures in the morning, not even half of the students were attending. All the prominent JVP activists like Bamunusinghe or Bikkhu Bhaddiya were absent.

Fifty years ago, 5 April 1971, was a Monday. I was an assistant lecturer in economics at Vidyodaya University during that time, a prominent stronghold of the JVP (People’s Liberation Front), which led the insurrection. When I went for my lectures in the morning, not even half of the students were attending. All the prominent JVP activists like Bamunusinghe or Bikkhu Bhaddiya were absent.

The whole campus appeared deserted. It was not a secret to us that the JVP might attack the Government at any time, but the exact date was not known. The news about the Wellawaya Police Station attack was announced on Radio Ceylon by midday. It was on the previous night. There was a stern warning from the Police not to get involved in any subversive activities.

The JVP cadres were supposed to attack all possible Police stations simultaneously on 5 April night in a bid to trigger a ‘revolution,’ but the impatient members at Wellawaya made the move a day before, unintentionally alerting the Police and the Government. Perhaps they received the wrong instructions about the date.

Those days, unlike today, the armed forces were small, and the Police were the main bastion of the State apparatus. Capturing power in that fashion by capturing Police stations however was impossible by any imagination. The more pertinent question was, what would they have done in case they had managed to capture power?

The background

It was less than a year ago in May 1970 that the JVP supported the United Front (UF) Government led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s SLFP, assisted by the two main left parties, the LSSP and the CP, to come to power at elections. Whether it was merely a tactic to first support and then attack, or whether they actually were disillusioned within a year, is a question of speculation. It could be both.

While unemployment, including graduate unemployment, was exceedingly high without a proper plan or solution after the election, the State repression also was high even curtailing any left-wing or youth activity in the country.

Just a year later, therefore, the JVP attempted to capture State power through extra-parliamentary means but miserably failed without popular support to the purported revolution. Compared to the previous radical or violent political events in the country, the uprising and its suppression were extraordinarily ferocious on both sides and created a chain of violent political cycles of which Sri Lanka has not yet been in a position to fully recover.

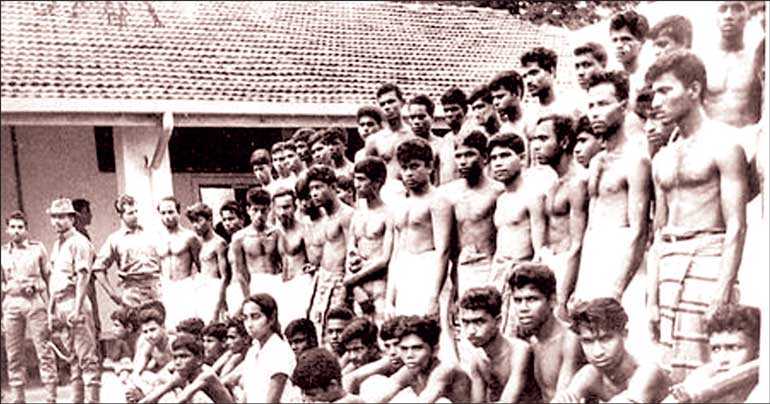

Although the major insurrectionary events lasted only for three weeks in April, it took nearly three more months to completely eradicate the rebellion outposts in the jungles and remote villages. The official death toll was 1,200 but unofficial figures reliably estimated it to be around 4-5,000. There are even higher estimates.

The insurrection by its very nature was to capture State power in fairly a democratic country at least at that time. It was not a spontaneous rebellion by the youth facing unemployment or any such hardships. It was a planned insurrection by the JVP, working as an underground insurrectionary party, of course affected by and utilising various socio-economic issues.

If not for those socio-economic grievances, large numbers of youth would not have joined the movement. In addition, the JVP considered the unemployed rural youth and university students as its political support base or vanguard. This theory resonated some of the New Left ideas of Herbert Marcuse or Jean Paul Sartre who sought new vanguards for contemporary social revolutions.

No serious attempts however were made to appeal to the other sections of the society. There was no serious trade union wing under the JVP at that time unlike today. Trade union struggles were considered ‘kanda koppa satan’ to mean ‘struggles for the porridge bowl.’ In that sense it was a left-wing adventure.

Insurrectionary influence

Insurrectionary influence

During the insurrection, altogether over 70 Police stations were simultaneously attacked and 40 of them were either captured or forced to abandon for security reasons. After assessing the security situation, when the Army moved in, the revolution however failed.

The 1971 insurrection in my opinion did not produce anything tangibly positive. It left only a legacy. It however created a culture of organised political violence that has been the bane of the country since then. It is arguable whether it was the outcome of a major malice underneath or the/a cause for the subsequent events. It is also argued that the LTTE not only was influenced but took the excuse or the example from the JVP insurrection.

The promulgation of the 1972 Constitution was completely unrelated to the event. The standardisation of university admissions in 1972 could be considered a distorted outcome of the insurrection, which on the other hand created grievances on the part of the Tamil youth. The 1971 insurrection was solely by the Sinhala rural youth.

One impact of the insurrection was the de-legitimacy of the incumbent ‘centre-left UF’ Government that slowly created conditions for the more ‘conservative UNP’ to take over the country in 1977. Or are we mixing up all the left-wing terminology to interpret the political history of the country upside down?

Judging by the fact that the JVP itself supported the UF to come to power at the 1970 elections, and launched the insurrection within a year, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the objective result of the insurrection was the strengthening of the political opposition in the country whether it was right-wing or not.

The JVP, the party that launched the insurrection, did not draw its lessons for posterity. It made a bigger mistake in 1987-’89. Only genuine admissions of ‘error’ came from some leaders who left the movement for various reasons. Although the number of the ‘deserters’ was significant, the impact remained inconsequential. Even there can be doubts whether they have drawn the correct lessons judging by the type of politics or activities that some of them have been involved in later.

There was some temporary admiration of the bravery of those who were involved in the insurrection by local and international commentators. Some of the local admirers came from unexpected quarters like independent intellectuals. Undoubtedly, the insurrectionists were brave to mean that they risked their lives or future for a ‘course that they believed in.’ That was mostly at an individual level and some of the leaders involved apparently proved to be some of the best brains in the country. They could have done a better service to the society or for social change if they were not lured to violence in that instance.

Different interpretations?

There were a plethora of literature or theories that attempted to understand and explain the event and its causes. Ian Goonetileke’s bibliography on the subject documents almost all the initial studies conducted on the insurrection. The most popular theories were in the sphere of sociology or political sociology that in fact argued for valid socio-economic and other grievances which supposedly led the leaders to lead the insurrection or the supporters to join the rebellion. There were around 16,000 who were supposed to have followed the movement directly and indirectly.

The population explosion, dysfunctional education, stagnation in the economy, rural poverty and more precisely the unemployment and graduate unemployment were highlighted as the salient socio-economic factors behind the uprising. All these undoubtedly were objectively verifiable factors that remained more or less on the same level or ferocity throughout the years of 1960s or 1970s.

Why then did the insurrection take place in April 1971? There were several political scientists who went slightly deeper into investigate the political circumstances of the insurrection and the ideology of the JVP, but soon conveniently fell back into the socio-economic explanations and more or less concluded that there had been something wrong in the society that led to the insurrection. There has always been something wrong with the existing society no doubt.

The left parities in the country were in fact were formed even prior to the independence to fight against these injustices or inequalities. But to wage war against a government that was elected with their own support on those grievances or injustices was completely a different matter. It could have come, under the prevailing circumstances, either from ‘left-wing idealism’ or from ‘quest for power’ for some reason.

While in the case of the 1971 insurrection, the first possibility was undoubtedly prevalent to a great extent, the second strand of motivation also cannot be ruled out. It was this ‘subjective aspect’ of the insurrection and the movement that many of the initial theories and interpretations of the 1971 insurrection neglected or failed to grasp. This subjectivity of the JVP ideology has been abundantly clear thereafter in its second failed attempt of insurrection in 1987-’89.

Relevant theories

Relevant theories

The frustration-aggression theory and the theories based on the same premises have failed to understand that frustration or underlying socio-economic grievances themselves would not automatically lead to aggression or rebellion without intermediary factors such as leadership, ideology, and organisation. This is common to both left-wing and right-wing movements.

Take the example of Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) in Sri Lanka or Proud Boys in the USA. It is the leaderships, organisations and ideologies that instigate organised political violence. This is what I mean by subjective factors in this article. Violence is not inherent; it is basically constructed, cultivated, and taught, either by the society or by political movements.

In the case of the JVP, its mastermind Rohana Wijeweera was instrumental in bringing a particular kind of violent political ideology to this country. It was during his studies at the Lumumba University in Moscow that he acquired, in my view and evidence, a distorted version of Marxism and revolution, like what Pol Pot of Cambodia acquired in France.

Wijeweera did not acquire his theories from the Russian revolutionary literature but from some contemporary pseudo-revolutionary theories popular among his contemporaries like Kassim Hanga of Zanzibar and Che Ali of Indonesia. Kassim Hanga and the group led a ‘one day revolution’ in Zanzibar in January 1964 which was successful and that was the model initially Wijeweera wanted to follow in Sri Lanka.

The broad spectrum of the JVP theory argued that revolutions are possible in different ways. The workers and peasants are not necessary. What is needed is the cultivation of a committed cadre organisation. Armed struggle and simultaneous uprising were the strategy. Undoubtedly, the prevailing economic and social grievances helped the JVP to convince 2,000 to 3,000 cadres to participate in the insurrection and over 10,000 youth and others to help them.

The ideology of the JVP at that time was a combination of a type of socialism and an extreme form of nationalism. The ‘Indian expansionism’ was one of their five classes. The main thrust of the ideology was the justification of violence under different pretexts and reasons.

There were of course excesses on the part of the counter-insurgency operations, but they were limited or mild compared to many other situations in the contemporary world or later events in Sri Lanka. There were no mass graves uncovered related to the 1971 insurrection. The suppression of the communist insurrection in Indonesia in 1965 was also a contrast. But it cannot be denied that both the insurrectionary and counter-insurrectionary measures since early 1971 finally led to the April insurrection.

Some of the measures, however, such as the declaration of emergency and arrest of suspects for security reasons left no option but Wijeweera to call for the insurrection somewhat carelessly on the night of 5 April. He was in jail and kept in Jaffna remand during that period. One objective of the insurrection was to rescue him from Jaffna jail by paralysing the country and forcing the Government to release him.

There were considerable excesses and violations by both parties. The rape and murder of Kataragama beauty queen, Premawathee Manamperi, was a high point of Army excesses. There were many innocents who lost their lives due to the events. I lost two of my friends who were active in the Ceylon Teachers’ Union but did not have any connections with the JVP. It was later revealed that they were killed to avenge a personal grudge by a Police officer.

Conclusion

Violence appears to be contagious. It is like a horrible epidemic like COVID-19. The insurrection changed the mindset of many people, alas negatively, both in authority and those who almost naturally opposed it, and on both sides of the ethnic divide. The reasons for the distinctions are not easy to figure. The insurrection opened the floodgates and Sri Lanka never could become the same.

Recurrent cycles of major violence were to follow, with a relative interlude after 1971 until 1983, in almost all spheres of political life from elections to ethnic relations, and political party competition until 2009 and even thereafter.

This has been the unfortunate saga of Sri Lanka for which collective solutions needs to be sought by all political parties, religious organisations, ethnic communities, and civil society movements. The present JVP hopefully could play a major role in this process through their experiences.

The JVP has played many positive feats lately being a critical opposition in the country and genuinely fighting against corruption. Since Sri Lanka is facing new challenges due to COVID-19 and international pressure/intervention on reconciliation, accountability, and human rights, whatever the temptation or provocation, the country should stick to nonviolent and peaceful methods.

The power of the mind and ideas might prove to be more successful than the power of the muscle or the arms. It only requires more discipline and more determination. It is the same path that the remaining rebels in the north and others should follow in Sri Lankan politics.

By Suriya Wickremasinghe

The 50th anniversary of the first JVP insurrection fell on 5 April this year. The insurrection was an event that shook our country as never before or since. During the course of 2021 we hope to retrieve from our archives, and place in the public domain, some of our hitherto unpublished documents of that time. For now, to revive older memories and inform younger ones, we list some relevant dates of that extraordinary decade.

13 May 1970: General Election results in United Front (UF) coming to power under premiership of Sirima R.D. Bandaranaike. The coalition is heavily dominated by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) but also comprises two left parties, the Lanka Samasamaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party (CP), J.R. Jayewardene is Leader of the Opposition.

July 1970: Members of Parliament form a Constituent Assembly, process of drafting new Constitution begins.

26 October 1970: Constitutional Amendment to abolish the Senate introduced.

13 March 1971: Rohana Wijeweera, Leader of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP/People’s Liberation Front), arrested.

16 March 1971: Emergency declared. Wijeweera continues to be detained, now under Emergency Regulations.

5 April 1971: An insurrection, mainly of rural youth, led by the JVP, breaks out in the form of simultaneous attacks on some 74 Police stations in various parts of the country. (Another 18 are attacked in the next few days); 35 Police areas temporarily fall almost totally under insurgent control. The insurrection is speedily suppressed with considerable ruthlessness, and in its immediate aftermath some 16,000 persons are arrested and held under Emergency powers.

14-15 May 1971: In the last session of the Senate before its abolition, independent member S. Nadesan QC makes the first notable public speech on the April insurrection.

21 May 1971: Bill to abolish Senate passed.

September 1971: First Amnesty International Mission to Sri Lanka (report published March 1972).

4-5 April 1972: Act creating Criminal Justice Commissions to try insurgent suspects debated and passed.

22 May 1972: New Constitution adopted. “Ceylon” becomes “Sri Lanka”, a Republic.

12 June 1972: Trial, under Criminal Justice Commissions Act, of alleged leaders of the April 1971 insurrection, begins. Commission consists of Chief Justice H.N.G. Fernando (Chair) and four others.

20 December 1974: After two and a half years, the above inquiry ends with the Criminal Justice Commission delivering its decision. Some including Wijeweera sentenced to imprisonment, some given suspended sentences, some acquitted. Trials of numerous other groups on a regional basis continue.

15 or 16 February 1977: By this time the ruling coalition has broken up. Emergency, which had commenced in 1971, lapses. Result is persons held under emergency regulations are released. The proscription of the JVP automatically lapses, though members serving prison sentences remain in jail. Lapse of proscription enables JVP to take part in the General Election.

21 July 1977: General Election results in UNP coming to power under premiership of J.R. Jayewardene. Leader of the Opposition is A. Amirthalingam of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), it having 17 seats as against the SLFP’s eight.

4 October 1977: Amendment to the 1972 Constitution, creating an executive presidency, passed.

2 November 1977: Pardon announced for all persons serving sentence under the Criminal Justice Commissions Act, and they are released. This includes Rohana Wijeweera and other JVP leaders.

Around this time, the Criminal Justice Commissions Act is repealed.

(The above is drawn from the publication ‘21 YEARS OF CRM: An annotated list of documents of the Civil Rights Movement of Sri Lanka 1971-1992,’ compiled by Manel Fonseka and Suriya Wickremasinghe, Colombo: CRM, 1993.)

(The writer is Secretary, Civil Rights Movement.)