Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 15 September 2020 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The micro, small, and medium enterprise (MSME) sector in Sri Lanka accounts for 90% of all businesses in the country, provides 45% of employment, and contributes 52% to the nation’s GDP. Successive Sri Lankan  governments have, thus, correctly identified the importance of MSMEs as one of the main drivers of growth and development. However, while this sector makes up the backbone of the Sri Lankan economy, it continues to be one of the most vulnerable to local and global economic disruptions.

governments have, thus, correctly identified the importance of MSMEs as one of the main drivers of growth and development. However, while this sector makes up the backbone of the Sri Lankan economy, it continues to be one of the most vulnerable to local and global economic disruptions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the traditional vulnerabilities amongst MSMEs, such as low levels of savings, assets, and inventories, consequently creating a unique set of associated policy challenges. However, any policy measures in response have to account for Sri Lanka’s narrow fiscal space and concerning macroeconomic fundamentals.

Immediate support: Addressing the nuances of liquidity shortages

There are two distinct aspects related to liquidity that are often conflated: liquidity amongst MSMEs and liquidity within the banking system. During the past five months, lockdowns, border closures, and social distancing regulations have all led to a sudden and significant fall in income for MSMEs.

With little liquidity in reserve, therefore, firms are struggling to survive without downsizing, laying off workers, and in some instances, completely shutting down operations. Disruptive impacts of COVID-19 on economic activities, especially in vulnerable sectors such as tourism, have led to Sri Lanka’s highest unemployment rate in a decade. MSMEs, therefore, are desperately in need of liquidity injections to survive these immediate shocks.

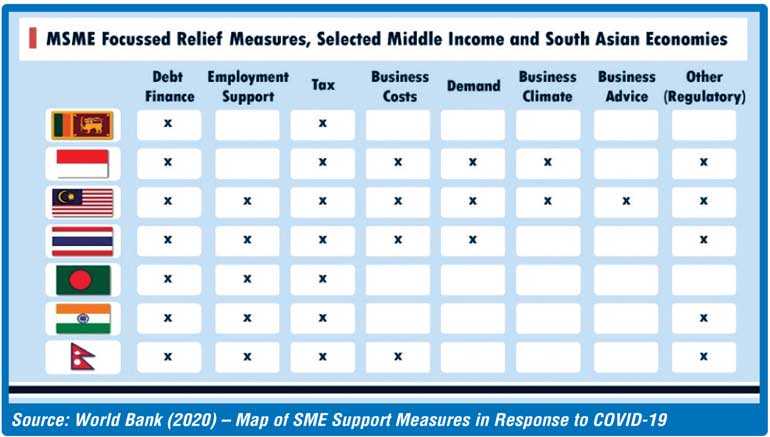

Middle-income economies around the world have responded through a variety of policy options (table below). However, due to the limited fiscal space available to Sri Lanka, the policy response thus far has been largely restricted to monetary policy and debt finance instruments, in the form of debt moratoriums and loan guarantee schemes to cover working capital expenses of MSMEs.

While loan guarantee schemes have increased the level of liquidity within the banking system structural limitations have reduced the benefits to MSMEs. Given the current economic uncertainty and the high probability of loan defaults, banks are rightly risk-averse in approving loan disbursements. Unfortunately, as noted earlier, MSMEs have worse credit histories that affect their risk assessments and have limited access to these new working capital loans.

One possible policy option to reduce the burden on the banking sector and allow them to disburse loans more confidently is through the implementation of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) – a temporary public entity tasked with the specific purpose of facilitating new working capital loans for MSMEs.

The unique benefit of an SPV of this nature is in its risk-sharing mechanism, whereby part of the loan will be secured by assets of the Central Bank-backed SPV and the rest undertaken by the lending bank. The SPV, concurrently, reduces the fiscal burden on the government that gets accrued through direct fiscal spending, while preserving Central Bank independence and banking sector stability.

In addition to monetary policy solutions and direct stimulus packages, many countries have also undertaken policies such as wage subsidies. Although resource-rich economies are capable of subsidising full wages or a majority proportion of wages, smaller economies with narrower fiscal space have undertaken more targeted subsidies.

For instance, the likes of Nepal have taken to subsidising the proportion of the wage employers are supposed to pay to the contributory pension fund (the ETF/EPF equivalent). Even though it is a small proportion of the total wage, such a subsidy provides valuable relief to MSMEs and mitigates some job losses.

Transition period: Non-stimulus solutions

Beyond monetary policy and fiscal policy measures, however, governments around the world have implemented a range of measures to support MSMEs’ transition through the pandemic that do not incur a significant fiscal cost, and thus, relatively accessible to the likes of Sri Lanka.

For instance, Greece, an economy that faces similar fiscal pressures to Sri Lanka, has initiated a digital solidarity initiative, a platform where large tech corporations provide free online marketing and account management training to MSMEs. This is to help MSMEs reduce their operational costs, increase efficiency, and transition onto e-commerce and digital platforms to mitigate the effects of lockdowns. In this instance, the government becomes a conduit, without incurring a cost, which in turn facilitates stronger supply chain link creation between domestic MSMEs and larger firms as well.

Measures that develop domestic supply chain links among MSMEs to facilitate greater innovation and value addition are more effective than protectionist policies and import restrictions. MSMEs tend to operate on thin profit margins and import restrictions price out or completely shut out firms from accessing vital raw materials. This is especially problematic when suitable alternatives aren’t easily available locally. Overall, therefore, heavy import restrictions tend to be counterintuitive towards developing and improving the competitiveness of Sri Lanka’s MSME sector.

Moreover, under the current circumstances, as global supply chains are being recalibrated and economies look for new sources and products, competitive Sri Lankan MSMEs could potentially make inroads into previously untapped foreign markets.

Furthermore, the past five months have highlighted the urgent need for better data on the MSME sector. The high proportion of informality amongst SMEs had led to a scarcity of data and thus affects the government’s ability to deliver targeted relief measures. Improving data collection, however, does not necessarily require formalisation.

A policy of ‘managed informality’ would be more prudent and can be initiated by introducing an informal MSME database. Especially now, linking relief measures to registration with the database, alongside guarantees that the database is not being used for forced formalisation, would create an incentive for informal micro and small enterprises to register. In turn, the data gathered can be used for more direct and effective policy during times of crises such as the current pandemic.

The necessity for modern solutions

The COVD-19 pandemic and its resultant economic upheaval is a uniquely 21st century problem, deeply intertwined with public health, global supply chains, and a growing digital economy. It requires a shift away from archaic 1970s policies and a greater focus on innovative solutions.

Current trends suggest that Sri Lanka’s path towards a complete economic recovery will be relatively slow and dependent on several external factors as well. Nevertheless, a specific focus on dealing with MSMEs will be essential to facilitate this recovery. As such, while managing a narrow fiscal space, Sri Lanka should look towards complementing its traditional fiscal and monetary policy measures with other measures that support MSMEs to be more competitive in a post-pandemic world.

(This blog is based on IPS’ forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’ report on ‘Pandemics and Disruptions: Reviving Sri Lanka’s Economy COVID-19 and Beyond’.)

[Kithmina Hewage is a Research Economist, with research interests in international political economy include wto issues, trade and development, export competitiveness, and Foreign Direct Investment. He holds an MSc in International Public Policy from University College London (UCL) and a BA with university and Departmental Honours from the Johns Hopkins University, USA.

Talk with Kithmina – [email protected]]