Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 17 January 2020 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

January is here; the season CEB talks up power shortages to ask for emergency power, with a fresh push to get more coal power projects approved.

The grid has not improved since last year we saw this drama, apart from rooftop solar additions – which too has slowed due to the uncertainty created by the CEB and the former Minister. Sri Lanka has a power shortage at present and no conventional solutions in the horizon. It is time for us to think of new solutions that are cheaper, faster and sustainable.

Our current power deficit is during the daytime, and not during the evening peak as a load curve will show. At present, the difference between daytime peak and night peak is approximately 200MW, and this too is set to disappear in the next few years as the daytime demand grows faster than the night peak.

We have 3,500MW of power for evening peak – but because of the hydro reserves are being overused for daytime generation, we run out of water a some months into the dry season. If hydro reserves are used sparingly during daytime, we will not have shortages.

The need and urgency to add generation during daytime leads to a simple solution; solar PV based electricity. It is also the fastest system to add to the grid, and only second to wind power in cost.

Fast tracking solar rooftop schemes by removing the CEB approval delays, while giving tariff certainty to the potential rooftop solar investors seem a straightforward thing to do. Large rooftop owners – from factories, logistics companies and large Government buildings – along with smaller rooftops can easily add more than 100MW per year.

This is necessary but insufficient in scale. While it reduces CEB costs, it doesn’t help CEB wipe out its high cost legacy generation. For that we need a large scale solar PV program – but these have always been hobbled by land availability and access to transmission network. An island with high biodiversity, population density and conflicting land use demands constrains ground mounted solar PV.

Sri Lanka has perhaps the best potential for floating solar, with our diverse, large, distributed water bodies, both natural and man-made. It is time our hydrological treasure also help power our energy need.

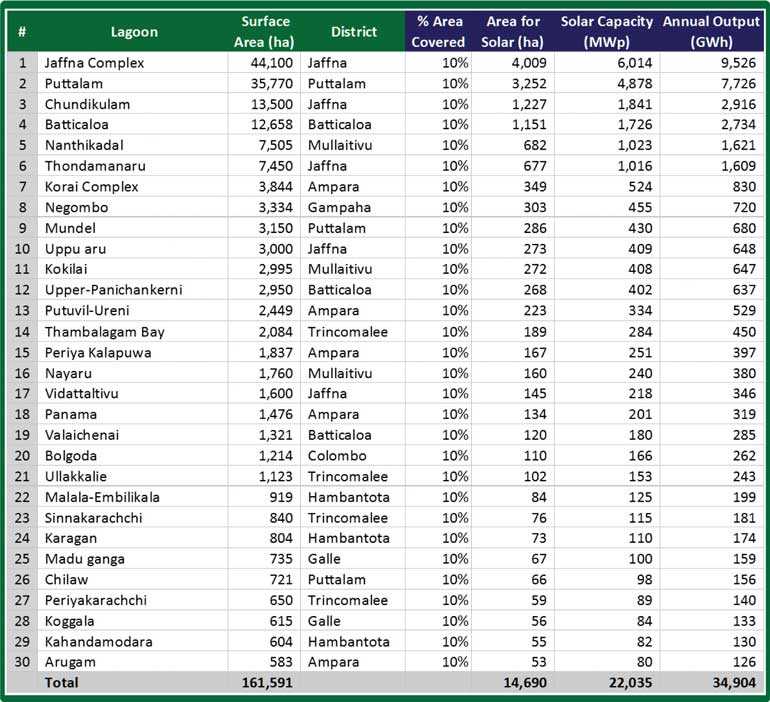

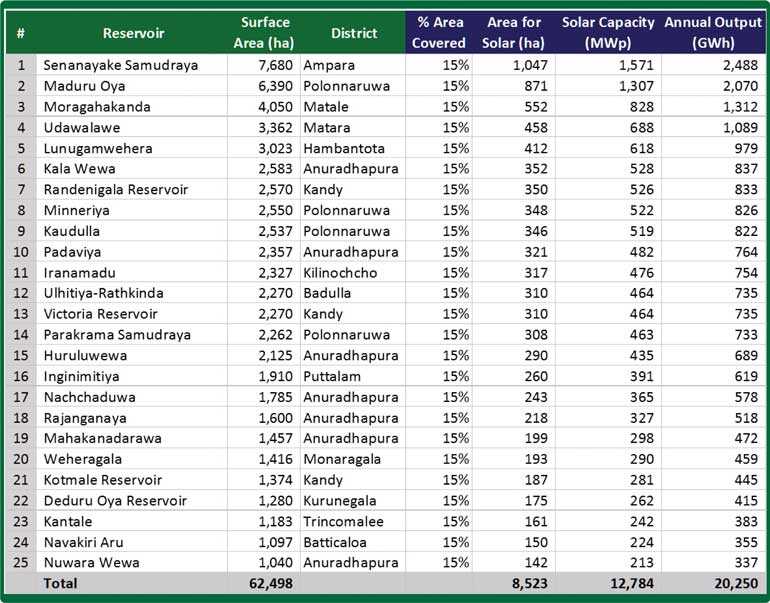

We selected the 25 largest reservoirs and the 30 largest lagoons of the country. We assumed 15% of the area of reservoirs and 10% of the areas lagoons will be used, and estimated how much floating solar PV can be added to the grid. It is possible to install 1.8MWp of solar cells on a hectare of water surface, harnessing more than 2.5GWh of energy per year.

The size of our water bodies is significant – spanning to more than 5,000 ha in the case of our largest reservoirs and more than 10,000 ha in the case of the largest lagoons.

This presents a potential solar capacity of 34.8 GWp, which will give us an annual energy output of 55,000 GWh. The energy demand of the country in 2020, according to CEB Generation Plan, is 18,542 GWh. 55,000 GWh exceeds the national energy demand for 2044, 54,963 GWh.

The peak demand by 2044 would only be 8,709MW. Therefore connecting bulk of this solar output to the national grid will not be possible if it remains synchronous (one that generates and consumes energy at the same time). We would need battery storage to connect some of the capacity to the existing transmission nodes – but this is not an immediate requirement.

What this shows is that we have the capability to generate all our energy needs from indigenous and renewable sources including solar, wind, biomass and hydro. Especially because our solar generation is highest during the time the wind and hydro is lowest, giving perfect complementarity. It will also cost less compared with fossil fuels, be it coal, natural gas or oil.

The technology to harness the same, and stich it to a fully functional and stable grid already exists – storage devices to store energy to use in the night, battery systems that give systems stability by evening out voltage and frequency issues, HVDC transmission networks and even digital inertia for the grid, which Tesla is now piloting in South Australia. There are more technologies in the pipeline, including generating hydrogen from solar power that can then be burnt in gas power plants – without the pesky carbon dioxide – currently being worked on in Australia and Los Angeles.

The idea is not new – huge solar PV arrays in the Sahara desert powering Europe through HVDC lines has been on the drawing boards for more than 20 years. And recently, a project was floated to set up a 10GW solar PV system in Western Australia with the intent of supplying solar based electricity to Singapore through undersea HVDC cables. Ours solution has both the generation and use within the country itself. In April 2019, Thailand tendered its first floating solar proposal – a 2.7 GW system across nine reservoirs.

Benefits of floating solar

The first benefit is the rapid development of generation capacity that can take Sri Lanka out of the present crisis, and cheap electricity to reduce the losses of the CEB. After implementation, we do not need to have any more emergency power conversations from 2021, and leave behind coal power as well. The pricing is affordable – the recently awarded 1GW floating solar project in India cost $ 700 million – a mere Rs. 126,000 per kW. If we use a more elevated figure – say Rs. 150,000 per kW, we can provide electricity to the grid at Rs. 11.00 per unit flat rate across 20 years, a price that would only compete with wind, and definitely cheaper than Norochcholai coal power plant. The calculation considers an Equity IRR of 11% on USD, USD debt and an annual 3% Rupee depreciation.

If we use the same assumptions for a new coal plant coming into operation in 2025, the first year cost would be Rs. 21 per unit with the costs in the 20th year going over Rs. 31 per unit (using conservative assumptions).

In arid climates, the evaporation rate of the area covered reduces by 80% saving precious water, and cooler temperatures on water increases electricity generation.

Implementation

While we worry about the adequacy of generation, one major hurdle of our grid is the inadequacy of our transmission network. This is what foiled the former minister’s attempts to bring a Turkish powership – he couldn’t find a convenient location to plug into the transmission network. The first step is to identify the water bodies close enough to the transmission network which has adequate capacity.

In this sense, there appears to be early candidates – Puttalam lagoon, Negombo lagoon, Randenigala reservoir, Batticaloa lagoon, Maduganga lake, Sorabora wewa in Mahiyanganaya, Chandrika Wewa in Embilipitiya, Nuwara Wewa and Nachchaduwa in Anuradhapura all are prime candidates, with Jaffna emerging as a fantastic location to be powered with wind+floating solar+battery storage hybrid mini-grid.

While not needed immediately, adding some storage can help even out some challenges too. For one, storage can be used to even out some intermittency issues due to cloud cover changes, as well as designing a 16-hour operational grid with four hours of storage. If four hours of storage is added, the batteries can store the peak generation and flatten out the energy supply curve – this will provide more energy within the limitations of the transmission network. Even with this addition of storage costs will be cheaper than a new coal plant (and faster). We are at the best moment to seize this opportunity – a new President with a bold vision, who has made a clear commitment to the environment and decarbonisation. The SLPP policy manifesto says “we also anticipate that hydro and renewable energy together would account for 80% of the overall energy mix by 2030,” (SLPP Policy Manifesto, page 58), which does not provide for any further addition of coal power nor gas power beyond what is in the pipeline.

What we need is ambitious action, and this proposal is one that should be sitting on the policymakers’ desk.