Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 7 February 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Seventy-two years ago, Sri Lanka gained independence from the shackles of British rule. This meant the autonomy to govern our people, the freedom to create and maintain our institutions and the ability to carve our own political narrative. Beyond political liberty, independence also restored our control over land, resources, and Sri Lanka’s economy; we obtained the prerogative to our prosperity.

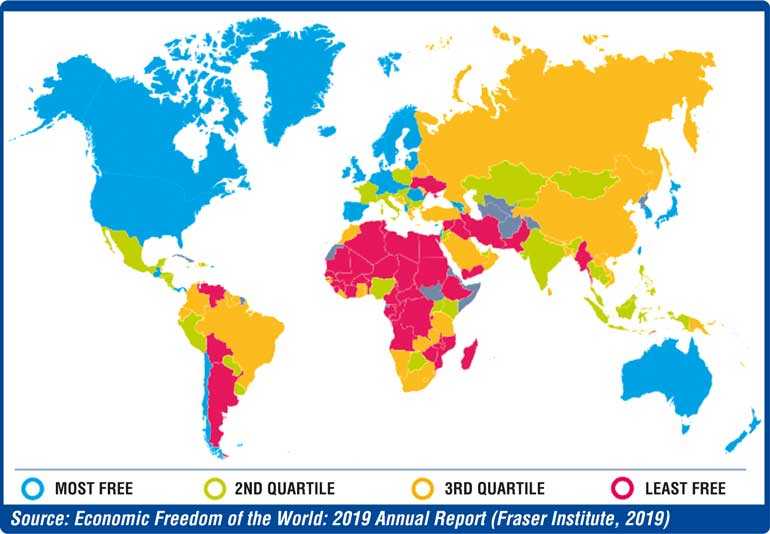

Reflecting upon the speech delivered by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa on Independence Day, it is clear that the modernisation of restrictive and out-dated systems, ensuring the increase of efficiency within local institutions and curbing corruption are well within the new Government’s mandate for the country.1 Upon welcoming this anniversary, and amid the dawn of a new decade, it is important that we do more than celebrate the past - it is time to reflect on the extent to which we have secured our future. The most recent revision of the Economic Freedom of the World Index ranks Sri Lanka at 104 out of a total of 162 countries.2 While our ranking places us at the lower end of the spectrum, we fare exceptionally poorly on the ‘Legal System and Property Rights’ indicator with an overall score of 4.91 out of 10. It is clear that Sri Lanka has taken certain measures and improved our overall score for Economic Freedom throughout the past few decades and consistently increasing its ratings, apart from the slight deviation from 2015-2017.

However, our pace towards such progress and reform has been sluggish compared to that of other countries and our regional competitors3. This is reflected in our overall rankings on the Index as they have consistently deteriorated from 1980 (ranked 68) to 2017 (ranked 104) even as our scores inched higher over time.4 Given the relative progress and prosperity of other nations that have scored and ranked higher on the index (such as Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and India) it is evident that Sri Lanka has to prioritise similar reforms - starting with our most vulnerable areas - in order to improve our economic and political future.

Main problem areas

Under the ‘Legal System and Property Rights’ indicator, our lowest performances are for the sub-indicators ‘legal enforcement of contracts’ and ‘impartial courts’ where we score 3.61 and 3.74 out of 10 respectively. Sri Lanka’s legal system is notorious for being riddled with corruption, lack of transparency and inefficiency.

In 2018, the Ministry of Justice revealed that 697,370 court cases had been brought forward from 2017 in addition to the cases filed that year itself; at the end of 2018, a total of 775,620 cases that were due to be settled were still pending in court.5

Despite the effects of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution that significantly curtailed the excessive control and influence of the executive, alleged corruption and manipulation of the judiciary has still been prevalent due to the persistence of political appointments and the intimidation and transfer of judges upon behaviour that is unfavourable to those in power.6 Therefore, the ability to hold politicians and officials accountable has remained challenging, especially in the lower courts, leaving civilians untrusting of and unsupported by the legal system.7

Furthermore, the time and cost required to enforce a contract through Sri Lankan courts is considered extremely arduous and time consuming compared to the processes of other economies within our region; we rank 164/190 with an overall score of 41.2/100 for ‘Enforcing Contracts’ under the Ease of Doing Business index published by the World Bank.

The state of property rights in the country is similarly complicated and ruptured. While there are many delays and inefficiencies in procedures such as registering property, some of these issues are often linked to issues within the legal system as well. The inability to quickly settle minor disputes over land ownership and the struggle to find relevant records within out-dated systems of data collection further deteriorate our standing in terms property rights. Sri Lanka scores particularly low on the sub-indicator ‘Quality of the land administration index’ under ‘Registering Property’ for the Ease of Doing Business index (scoring 5.5/30).8

Impacts of our weak systems

Apart from affecting the general security, autonomy and free-will of individuals within our country, Sri Lanka’s inability to maintain and improve the status of its legal systems and property rights has had significant impacts on the state of our economy and future prosperity as well.

The perceived instability and corruption within the legal system often leads potential investors and business away from the country due to their doubts about the strength of the rule of law and its enactment. The likelihood of commercial disputes being prolonged and unjustly handled by the courts further harms our prospects of attracting local and foreign commerce into Sri Lanka. The inefficiencies of the legal system also render it an unreliable solution to the woes of local entrepreneurs and small businesses; acting as a legal barrier to their growth and development.

Moreover, the disputes, bureaucracy and technicalities that convolute property ownership in Sri Lanka further deter the emergence and growth of new businesses and entrepreneurs that could enrich our economy. For example, the inability for many individuals, such as farmers, to secure titles to their land severely curbs their ability to invest and make full use of the property they cultivate within.9

It also inhibits the growing land markets and the potential to use land as collateral within the country. Such issues squander the potential of our youth, resources and skills and ultimately hinder the progress of our entire nation.

The pathway to reform

Given the above problems and their precarious effects on our economy, it is clear that Sri Lanka needs to prioritise reform for its two most vulnerable areas that have long been neglected by politicians and those in power.

Readdressing the promises brought out by the former Minister of Digital Infrastructure and Information Technology Ajith P. Perera in September 2019, one major leap in streamlining and reforming our legal system would be looking towards digitisation.10 While it would be a long term investment and a difficult step for Sri Lanka, it would be a crucial step that may concurrently curb the corruption, manipulation and inefficiency of our current system as well as improve upon the system’s transparency and accessibility to the public. As Dr. Laksiri Fernando presented in 2019, digitisation of the court system “could not only expedite legal proceedings, crime control and civic justice,” but also “ensure common standards throughout the country” in terms of how proceedings take place and how all citizens are treated within the court system.

Human errors and language barriers may also be overcome while reducing the time and cost of legal proceedings for both the government and civilians.11 Furthermore, the digitisation of legal records including those related to land ownership could prevent the misplacement and damage of relevant documents in the case of necessity.

The “e-land” initiative by the Registrar General’s Department to enable the digital protection and registration of legal documents pertaining to movable and immovable properties may be considered a good first step.

In his speech, the President acknowledged the importance of an independent Judiciary “for the well-being and advancement of any democratic society” as well as affirmed the need to revise systems that prevent people from freely undertaking self-employment or engaging with businesses.12 While this admission on the need for reform is commendable, it is necessary that we ensure it more than mere rhetoric that placates us as weak institutions persist over time.

A completely functional digital court system may still be quite a challenge that will require constant dedication and fruitful efforts in order to be successfully implemented. In the meantime, it is crucial that the government takes all possible measures to focus on the improvement of our legal sector and the fortification of our property rights as they are fundamentals to ensuring the protection of individual liberty as well as the state of our economy.

Free from the limitations of our colonial past, land and time are priceless resources that are well in our hands; Sri Lanka’s progress is now contingent upon our prioritisation. Ultimately, a nation is only as independent and free as its people are; if Sri Lankans cannot be promised security through law and access to land, it appears the fight for freedom is still ongoing.

(Erandi de Silva is a Research Intern at the Advocata Institute, and can be contacted at [email protected] and @randyyrando on Twitter. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute.)

Footnotes

1Daily News, “President’s speech at the 72nd Independence Day celebrations”, February 4, 2020, https://www.dailynews.lk/2020/02/04/local/210407/presidents-speech-72nd-independence-day-celebrations (Accessed February 5, 2020).

2 James Gwartney,et al., Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report (Canada: Fraser Institute, 2019), page 9, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2019.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2020).

3 Ian Vásquez and Tanja Porčnik, Human Freedom Index, 2019 (United States of America: Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute, and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, 2019), page 49, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/human-freedom-index-2019-rev.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2020).

4 Gwartney,et al., Economic Freedom of the World, page 162, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2019.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2020).

5 Government of Sri Lanka, Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and Legal Reforms, Statistical Records on Cases 2018, 2018, Colombo, https://moj.gov.lk/web/images/pdf/other/Stat-2018-MOJ.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2020).

6 GAN Integrity, “Sri Lanka Corruption Report”, GAN Business Anti-Corruption Portal, August 2017, https://www.ganintegrity.com/portal/country-profiles/sri-lanka/ (Accessed February 4, 2020)

7 Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Sri Lanka (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018), page 9, https://www.bti-project.org/fileadmin/files/BTI/Downloads/Reports/2018/pdf/BTI_2018_Sri_Lanka.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2020)

8 World Bank Group, Doing Business 2020 - Economy Profile of Sri Lanka, (The World Bank, 2019), page 4, https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/s/sri-lanka/LKA.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2020).

9 Dhananath Fernando, “Price controls no solution to rice crisis”, Advocata Institute, January 13, 2020, https://www.advocata.org/commentary-archives/2020/1/13/price-controls-no-solution-to-rice-crisis (Accessed February 4, 2020).

10Ashwin Hemmathagama, “Govt. to digitise court system”, Daily FT, September 4, 2019, http://www.ft.lk/news/Govt-to-digitise-court-system/56-685086 (Accessed February 4, 2020)

11 Laksiri Fernando, “Digitization Of The Court System: Reality Or Rhetoric?”, Colombo Telegraph, September 7, 2019, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/digitization-of-the-court-system-reality-or-rhetoric/ (Accessed February 4, 2020)

12 Daily News, “President’s speech”, https://www.dailynews.lk/2020/02/04/local/210407/presidents-speech-72nd-independence-day-celebrations (Accessed February 5, 2020)