Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 12 March 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is election time again – this time for aspirants to get elected and vest themselves with power in governance through the main Legislature, the Parliament.

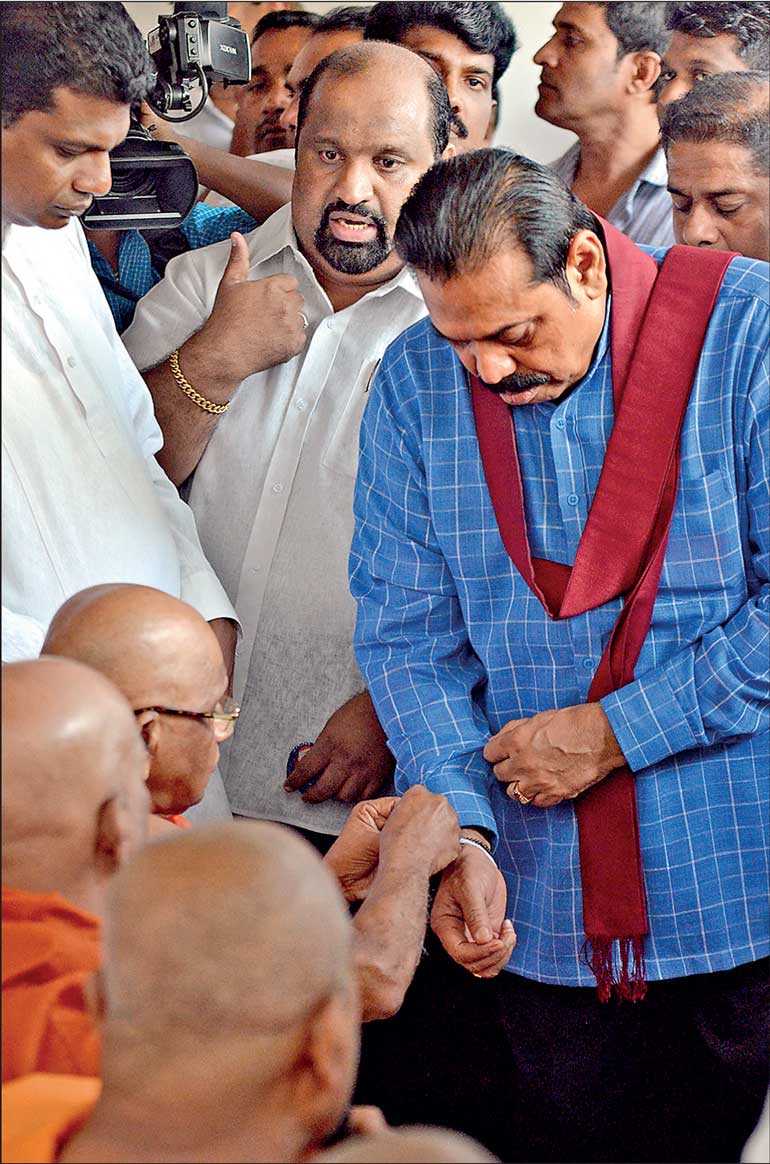

The leaders of political parties and coalitions and their members nominated to contest will now be rushing to seek the blessings of the Chief Prelates and other religious leaders. They will hand handover copies of their manifestoes and explain how they will implement the policies in realising the expectations of society. They will also confirm their personal commitments to serve the nation and its people with honesty, integrity and professionalism; and promise to abide by the most sacred codes of conduct, ethics and religious teachings.

The voters will silently watch this charade and even possibly be gullible enough to believe in these policy statements and commitments and exercise their votes in favour of the parties and candidates concerned.

The political leaders who pay a call and seek blessings from the Chief Prelates are now joined by key members of the Executive, including ministry secretaries, commanders of the armed services, chief of elections, those appointed as judges, diplomats, independent commission members and as civil society leaders. The latest meeting with the Chief Prelates was by the members of the March 12th Movement; where the March 12 declaration seeking to create a favourable political culture was signed by the Chief Prelates of the Three Sects on 7 March.

After signing the declaration, the Anunayake of the Malwatte Chapter said: “We are collective of the opinion that the corrupt individuals should not be given nominations. At the same time, there are monks who should be worshipped. If they are going on the wrong path, we should point them out. We are against selling our country and looting its resources. Selling chunks of our land on lease for 100 or 99 years is a serious crime.”

Once the elections are over and the elected are installed in their exulted positions of power, the manifestoes, policies, commitments and promises will be out of scope; and the elected members will not be bound nor accountable to honour the solemn promises given in the run up to the elections. These commitments will also be forgotten by the majority of voters, who voted with expectations and belief in them being delivered as promised.

Civil society

Civil society had on several occasions called for these manifestoes and commitments to be codified in to social contracts. Despite recognising that any such social contract is legally unenforceable against the political party or individual members of a party, civil society was yet keen on extracting a ‘Moral Commitment’ from the elected leaders with options to name and shame them post victory, when thee elected fail to honour their commitments. Civil society was inadequately backed up in this exercise of the demand of accountability and in the expression of ‘naming and shaming’ by the society itself in the post-election periods.

Even when promises were dishonoured and violated with impunity, openly, blatantly and with much negative impact on the economy, society and the nations, there were little advocacy and pressure applied by civil society leaders; and certainly no impactful ‘naming and shaming’ nor street protests were seen actively supported by citizenry in general (i.e. with the exception of some sporadic protests and media exposes). The best example of this was an attempt by a leading chamber to develop and publish a quarterly update feedback on annual budgetary commitments, which was stopped by black mail actions of the then Secretary to the Treasury.

In the later years, especially during the last regime in power, Verite Research made substantial progress and has succeeded in developing budget tracking and fact checks. Three cheers to them and also to the initiatives simultaneously launched by the Parliamentary Public Finance Committee under the Chairmanship of MP Sumanthiran which also needs to be commended.

In the context of the impending elections, the recognition of the political advantages in being blessed and endorsed by the power and position in society enjoyed by the venerable Chief Prelates, and their willingness and commitment to endorse a civil society accord on good political governance, leads the writer to suggest that: Civil society collectively canvas, advocate and pressurise all leading political parties and coalitions contesting the 25 April Parliamentary Elections to have their manifestoes and commitments to be developed as a formal social contracts; and for these contacts to be signed at transparently broadcast ceremony by the key officials of the relevant parties, before the Chief Prelates, the Archbishop and the Presidents of All Ceylon Hindu Congress and All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama, all of whom will sign as witnesses along with the Chairpersons of the Elections Commission and Human Rights Commission and three most recently retired Chief Justices.

Singapore

This recommendation comes in the context of Singapore being held up as the most desired benchmark for effective good governance by most elders in Sri Lanka; whereas the Singapore Think Centre – Towards a Vibrant Civil Society – advocates in the following posting that even “Singaporeans need a revitalised social contract”; this is an important lesson for civil society in Sri Lanka to follow as it sets out a ‘Way Forward’ path to evaluate its applicability; and adapt it appropriately, in the time prior to the next Parliamentary Elections;

Our island state was founded more than 50 years ago on the basis of “one united people, regardless of race, language or religion, to build a democratic society, based on justice and equality, so as to achieve happiness, prosperity and progress for our nation”. These ideals are enshrined in the pledge that is recited by all students before class starts every day and takes prominence during National Day celebrations.

Half a century later, these very ideals have been eroded to the point where the livelihood of citizens are threatened with rising housing, education and basic living cost with no assurance of any benefits from the wealthy state for citizens to ease their retirement after giving their lives to building the nation.

Instead, wealth inequality has not improved in the last five years and income growth has slowed across the board except for the wealthiest. No matter how much assistance the government gives, there will always remain a segment of the population that cannot catch up. This is when social expenditure of the government must increase.

We need a government that provides a living wage, basic health, retirement security, unemployment insurance, for everyone to support their families. We need decent work to support decent lives. The current exploitative nature of work is unsustainable where its workers clocked 2,371.2 hours in 2016, the longest in the world. Our aspiration to be the Switzerland of the East is nowhere realised after half a century when our workers are among the oldest in the world with a lack of minimum wage in an economy that ranks fourth in the world for the highest cost of living in a Mercer’s survey conducted in June 2016.

It is ironic that the hardworking and old Singaporean workers cannot afford to retire even after a lifetime contributing to the nation’s economy. This is because Singapore refuses to sign all the ILO’s core labour standards (signed 5 Core Labour Standards) after so many years of guaranteeing a minimum standard for its workers. Instead, it justifies its exclusion with its famed tripartite arrangement between government, unions and employers.

Even judging by its own justification, one is hard pressed to see how the workers’ welfare is considered when the unions are helmed by government officials, a role passing like musical chairs to prominent members of the Cabinet past and present along with other positions as heads of large government linked companies (GLCs). These giant conglomerates are built by the compulsory savings of ordinary Singaporeans who reaped none of the returns, except for miserable interest that barely keeps up with the inflation rate. The government is the largest employer in Singapore and together with the GLCs controls the economy of the country.

Social contract

We turn now to ask, what then is the social contract of Singaporeans with regard to its employers and government? For this, we must look at the origins of the theory of the social contract which points invariably to the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius while tracing his inspiration to the scholastic theologian Francisco de Vitoria. From both we discern the values that undergird the concept of the social contract, an inherent concern for “a noble and liberty-loving heart, a sense of truth and justice which kept him from error… [and] condemned injustice wherever he discerned it.”[1]

These ideals echo the aspirations of our early leaders who enshrined the values in the pledge all Singaporean students recite by heart daily. These are also the values encapsulated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which the United Nations’ General Assembly, which Singapore is a part of, has agreed to support.

Specifically, goal 16 of the SDGs is dedicated to the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies with provisions to protect civic freedoms, ensure equal access to justice and uphold the rule of law. Goal 16 can only be realised if the role of civil society is respected and civic freedoms are protected.

But it is hard to believe that Singapore can promote or protect such freedoms when it goes to the extent of persecuting an individual for expressing his own opinions in a private Facebook posting to his friends. How can an august institution like the judiciary have its reputation compromised in any way by a single Facebook post? Must they impress their power and assert their authority to prosecute an individual however misguided his/her opinions might be?

How can we reclaim our freedoms and dignity when oppressive laws like the Internal Security Act and individuals being prosecuted for their opinions still loom over all citizens, casting a chilling pall across society? The concern to overcome terrorists’ threats is adequately covered by many other legislation and there is no need for such archaic and draconian laws. This is especially true when its use has been leveraged more against political opponents than real national threats. Of the hundreds of detainees incarcerated, many were ordinary citizens like teachers, social workers, theatre practitioners and lawyers.

We urge the government this national day to help citizens overcome various injustices, whether economic, social, political or cultural and truly realise the values in our national pledge.