Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 13 August 2018 00:52 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Trade and Development Strategies Minister Malik Samarawickrama presenting the National Export Strategy (NES) to Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. EDB Chairperson Indira Malwatte, ITC Geneva Executive Director Arancha Gonzales and European Union Deligation of Charge d' Affaires Paul Godfrey are also present – Pic by Lasantha Kumara

Critical issues relating to NES

In the previous two parts of this series (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Part-I--National-Export-Strategy-2018-22--Disrupt-the-economy-fast-if-the-goals-are-to-be-attained/4-659860; http://www.ft.lk/columns/Part-II--National-Export-Strategy-2018-22--Introducing-measurable-physical-targets/4-660298), it was pointed out that the National Export Strategy or NES released by the Export Development Board (EDB) was, though belated, a welcome development. It had paved the way for Sri Lanka to move away from the domestic economy-based economic strategy, pursued by the previous administration, to an export sector-based economic strategy.

Given the limitation on the size of its domestic economy, Sri Lanka cannot bring about prosperity for people only by concentrating on the domestic economy. Hence, as Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe had pronounced in the first Economic Policy Statement (EPS), Sri Lanka needed to produce for a market bigger than its domestic market. But in the last three-and-a-half year period, the action by the Government, it was observed, to realise this policy pronouncement has been very limited.

In this background, EDB has now come up with a national strategy for developing the export sector and that strategy has to be converted to policy, to programs and to projects for implementation at the ground level. This was the responsibility of a game-changer, as was done by Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew or Korea’s Park Chung-hee.

Given the limitation on the size of its domestic economy, Sri Lanka cannot bring about prosperity for people only by concentrating on the domestic economy. Hence, as Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe had pronounced in the first Economic Policy Statement (EPS), Sri Lanka needed to produce for a market bigger than its domestic market. But in the last three-and-a-half year period, the action by the Government, it was observed, to realise this policy pronouncement has been very limited

EDB’s internal working goals

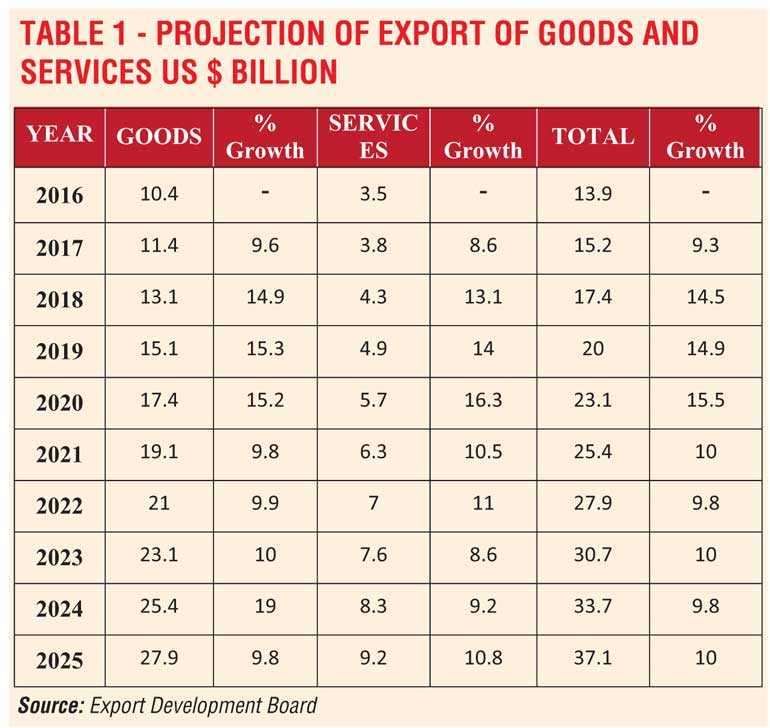

NES did not have annual growth targets for export of goods and services, except an end of the period goal of reaching US $ 28 billion by 2022. This was considered a serious deficiency in NES, since the authorities would not be able to gauge the success or failure of the strategy in the absence of measurable annual goal posts.

However, EDB has via email informed me that it indeed has working internal goals for export of both goods and services up to 2025, the end-year of the Government’s main economic strategy, titled Vision 2025. These internal working goals, as well as the percentage growth in each year, have been presented in Table 1. It is presumed that EDB has the detailed sectoral composition of these annual goals so that it would be able to ascertain growing and lagging sectors and take immediate corrective measures for any underperforming sector.

The year 2018 is already a write-off for NES

The importance of such measurable goal posts for implementing the export strategy can be ascertained by examining the annual goal post for the export of goods for 2018 and the achievements during the first five months of the year. The internal working goal of EDB in these exports for 2018 has been $ 13.1 billion, which amounts to an annual growth of 14.9%. However, during the first five months, the achievement has been only $ 4.7 billion which, compared to the first five months of 2017, has given 6.7% growth to Sri Lanka. When annualised for the full year, this achievement works out to $ 11.3 billion. It will be short of the EDB’s annual goal by about 14%, requiring it to diagnose the causes for underperformance and take immediate corrective measures to catch up with the lost goal.

To be on the goal, Sri Lanka has to accelerate its export performance from a monthly average of $ 900 million in the first five months, to a level of $ 1200 million per month in the balance seven months of the year. Percentage-wise, it amounts to a monthly growth of some 33%. It will be quite challenging for EDB to go for this target within this short space of time. If this target is lost, the cumulative losses built into the targets in the balance period of NES will become larger and larger in each successive year. It will surely derail NES from its planned target path. It, therefore, appears that 2018 is a completely write-off, as far as the goals of NES are concerned. This makes it necessary for EDB to revise the strategy, as well as the underlying goal posts for the whole NES period, and plan for a new life beginning from 2019.

Need for productivity growth at the national level

After the first two articles were published, several readers contacted me and made valuable suggestions regarding the whole NES. One such reader was the former Director General of Agriculture, Dr Sarath Weerasena.

Commenting on the strategy on the promotion of processed food and beverages, Dr Weerasena has pointed out that unless an overall national productivity growth strategy precedes the  growth of exports, there will be a shortage of nutritious agricultural crops in the domestic market, raising their prices and thereby depriving the local population of nutritionally superior foods. This is an important point on three counts.

growth of exports, there will be a shortage of nutritious agricultural crops in the domestic market, raising their prices and thereby depriving the local population of nutritionally superior foods. This is an important point on three counts.

First, unless there is an increase in productivity and yield rates, Sri Lanka will not have a surplus for exports. Any forced diversion of local products into the export market will starve the local markets.

Second, with the high cost of production of agricultural products, due to a host of factors ranging from low productivity to rising input prices, Sri Lanka’s agro-based export processing firms will find it difficult to get a competitive margin for their exports in the global markets. This challenge specifically comes from neighbouring India and Thailand, two countries which have successfully raised their yield rates through better technology, farming methods and farmer training.

Third, by obliging to the Government insistence, firms may get into the export markets initially, but when the heat of non-availability of a sufficient volume is felt, they will agitate for the import of such products to keep the factories running throughout the year. In that situation, Sri Lanka will get only the narrow value added margin from the export of processed foods.

An argument made in its favour will be that the country will benefit as long as the domestic value added is at least positive, the experience which Sri Lanka had when it embarked on apparel exports in early 1980s. But, a domestic processed food industry for exports cannot survive if it is dependent on imported foods continuously. Hence, the improvement of productivity and yield rates of key agricultural crops is a must if the country is to realise the goals of the national export strategy.

Going for new products

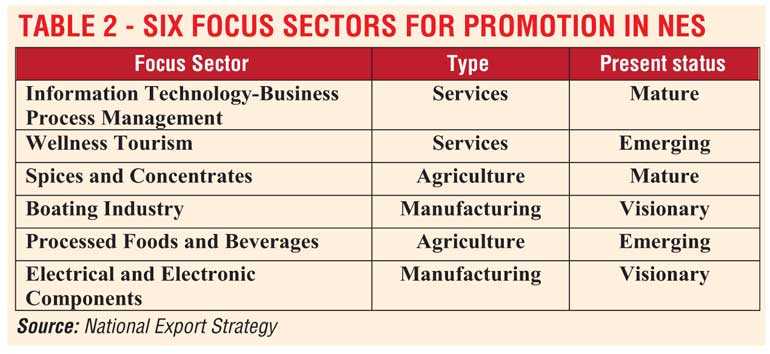

EDB has selected, after consultation with stakeholders in public and private sectors, six focus sectors for promotion as Sri Lanka’s future exports. The six sectors and their present status in the country’s production and export system are given in Table 2.

Sri Lanka’s saturated export structure

As at today, Sri Lanka’s exports to the rest of the world are being dominated by two product categories: apparels and ‘the three tree crops’ – tea, raw rubber and coconut. In 2017, in which its exports figures were the highest in the recent years, the former accounted for 44%, while the latter ‘three tree crops’ had a share of 17% of total export of goods. A brand new category that had been added in the recent decades had been manufactured rubber products – mainly solid tyres – that had acquired a share of 7%.

This has been the country’s export structure in the last four decades, and it has been happily savouring marginal improvements in these categories whenever such improvements occurred, as if Sri Lanka had hit the ‘next big thing’ in its exports. That complacency had sowed the risk viruses that have stunted its growth as a mature growth sector.

On the one hand, they had already reached the saturated point, given the country’s limited resource base. On the other, there were no new products added to the list, and worse, no concerted action had been taken to charter the unchartered territory of ‘services’. With proper logistics in place and elimination of unfriendly policies, services offer a good opportunity for Sri Lanka to bring its own next big thing in expanding the earnings base in foreign exchange.

The internal working goal of EDB in these exports for 2018 has been $ 13.1 billion, which amounts to an annual growth of 14.9%. However, during the first five months, the achievement has been only $ 4.7 billion which, compared to the first five months of 2017, has given 6.7% growth to Sri Lanka. To be on the goal, Sri Lanka has to accelerate its export performance from a monthly average of $ 900 million in the first five months, to a level of $ 1200 million per month in the balance seven months of the year. It will be quite challenging for EDB to go for this target within this short space of time

It is a quantum leap that is needed

In this background, EDB’s search for new products and identification of six focus sectors for growth are a salutary development. Since the existing structure of the export of goods and services is already saturated, what is at issue is whether the identified six focus sectors could facilitate Sri Lanka to make a ‘quantum leap’ and generate prosperity for its people. In the early 1980s when Sri Lanka ventured into apparels under its export processing zone strategy, such a quantum leap was delivered to the country, pushing its production frontiers outward. It generated employment, changed the structure of exports from agriculture-based products to industry-based products and marked Sri Lanka in the world export map as a leading apparel exporter in the world. The new focus products should generate similar results.

The six products are as follows: one, information technology and business process management; two, wellness tourism; three, spices and concentrates; four, boat building; five, processed food and beverages and six, electrical and electronic components.

Use Singapore-Sri Lanka FTA to tap the ICT sector

In EDB’s view, information and technology cum business process management together with spices and concentrates are mature sectors in the globe. Hence, Sri Lanka’s challenge is to grab a larger share in the market competing out the existing players who are already dominating the industry. Of them, information and communication technology is a game changing and also disruptive sector in the globe. With new inventions that hit the market as the next big thing every day, many nations, including Sri Lanka have been branded as ICT infants.

Since Sri Lanka lacks research and development facility, it has to necessarily jump on to the bandwagon of nations who have become masters in this particular science. Even to do so, the country has to create an ICT-literate and conscious nation across its population. This is what Singapore did at the turn of the new millennium, by requiring its universities and technical colleges to concentrate on ICT, among other focus fields. The results are dramatic and today, Singapore is a leading nation on novel ICT products such as robotics, artificial intelligence, and internet of things.

Sri Lanka cannot reach this level in short to medium term, and should get itself attached to a country or countries that have been masters of this science. The recently signed Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement provides an opportunity not to be missed by the country at any cost. However, it requires the country’s ICT professionals to make a self-assessment of their own capabilities in relation to fast-changing global trends, and look at Singapore as a benefactor rather than an exploiter.

Sri Lanka should overhaul its healthcare system

Though EDB has selected wellness tourism or providing superior medical treatment to patients who are to visit Sri Lanka as tourists, without logistics, governance principles and systems, right now, the country cannot expand this service to a significant level.

The private sector hospitals that practice Western medicine have to go through a complete overhaul if Sri Lanka is to attract patients compared to a country like, say, Thailand. These problems were analysed by me in a previous article in this series comparing Sri Lanka’s private healthcare system with that of Thailand (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/private-healthcare-providers-in-sri-lanka-should-benchmark-with-better-service-providers-abroad/4-189900). In the case of traditional medicine, the biggest hurdle will be the lack of worthwhile research into it as an effective curative system. These are matters beyond the control of EDB, and have to be resolved by the special focus groups to be set up under NES.

Limited scope of agriculture without creative research

Spices and concentrates and processed foods and beverages too have a limited scope with the country’s inadequate present research into this area, though EDB has identified them as the next big thing for Sri Lanka. It is therefore necessary to push the country’s universities and research institutes into full gear as a matter of priority for it to gain capacity as a top exporter in these areas.

Since the existing structure of the export of goods and services is already saturated, what is at issue is whether the identified six focus sectors could facilitate Sri Lanka to make a ‘quantum leap’ and generate prosperity for its people. In the early 1980s when Sri Lanka ventured into apparels under its export processing zone strategy, such a quantum leap was delivered to the country, pushing its production frontiers outward. It generated employment, changed the structure of exports from agriculture-based products to industry-based products and marked Sri Lanka in the world export map as a leading apparel exporter in the world. The new focus products should generate similar results.

Join the global production sharing network

A real scope is provided to Sri Lanka in boat building and electrical and electrical components, as the next big thing in promoting exports. But both need high technology and they have to be acquired at a cost from abroad. In boat building, it is necessary to get linked to countries which are already masters of the game, such as the Netherlands, Japan and South Korea. Even Chinese technology can be tapped with that country’s presence in the Hambantota industrial zone.

An important strategy to be introduced in both these types of products is not to produce a full product in the country. The essential strategy should be to produce only selected components and join the global production sharing networks. This is the strategy followed by countries in East Asia, such as Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines, when they penetrated the global high tech markets.

As I have pointed out earlier, preparing a strategy list is one thing. The challenge is to put it into practice. The whole Government machinery should be aligned to achieving this goal. That requires a capable game changer at the top.

(W A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])